Given exceedingly short shrift in its day. Viewed as in exceptionally poor taste. Marketed in some respects as Lord of the Flies Meets The Dirty Dozen. Audiences accepting of kids putting on a show or, the modern equivalent, making a movie, not so keen on youngsters going to war. In any case there’s an inbuilt repugnance as you get the distinct impression some of these kids would have been ideal recruits for Hitler Youth or the Mussolini version. And Italy, one-time ally of Hitler, becoming suddenly heroic seemed to jibe. Not to mention Rock Hudson’s marquee value fading fast after a gigantic turkey called Darling Lili (1969). Despite some distinctly unsavory aspects, bordering on exploitation, this seems enormously underrated, not just as an actioner, but for a raw depiction of war, far more realistic than many in the genre that toplined on violence.

Sure, it’s an odd concept, Italian kids, in the absence of adults, turned into a fighting force by dint of letting loose their innate venality and savagery. But they’ve not been washed up, adult-free, on a desert island. This small bunch have been orphaned and bloodily. Germans on the hunt for local partisans execute an entire village and then, finding a quisling, proceed to massacre the local resistance and for good measure destroy a team of American parachutists dropped into the area to facilitate the Allied advance.

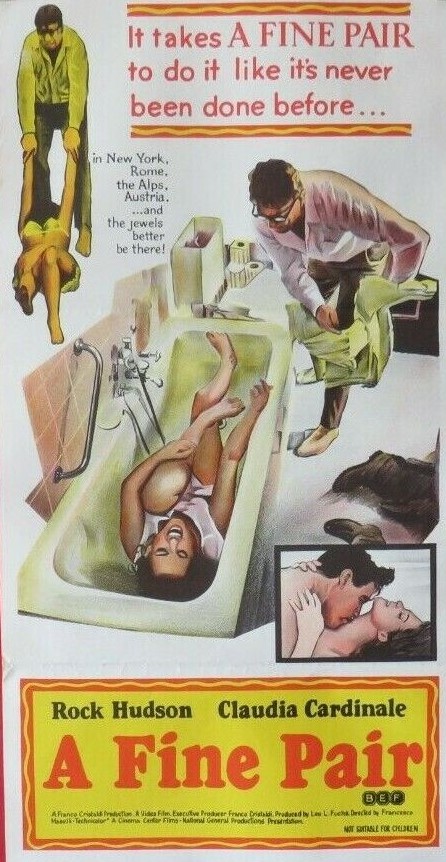

The kids come across the one survivor, Turner (Rock Hudson), hide him from the enemy and dupe German doctor Bianca (Sylva Koscina), sympathetic to the plight of the innocent, into caring for the wounded soldier. Rather than hang around and accept the ministrations of such a beauty and see out the war with a view to possible romance, Turner is intent on single-handedly completing his mission of blowing up a dam.

Given the kids have amassed a secret armory and are trigger-happy, desperate to avenge their parents, and getting down to the gung-ho aspects of war, Turner, with appalling disregard for their safety, decides to commandeer them for his own unit. Bianca objects and watches with horror and for most of the rest of the picture confines herself to the pair too young to be considered combatants and who reek of desolation or to find ways of killing Turner or betraying him to the Germans.

Meanwhile, the kids have their own ruthless leader, Aldo (Mark Colleano), one part John Wayne, one part the creepy Maggott (Telly Savalas in case you’ve forgotten) from The Dirty Dozen, who objects to taking orders. Training consists of little more than a bit of marching in file and learning how to quickly reload a machine gun. Turner’s clever plan is to use their perceived innocence to distract the Germans guarding the dam. The distraught Bianca, stepping out of line once too often, is raped for her trouble.

Setting aside all audience misgivings about the premise and the sexual undertones, the mission is very well done, plenty tension, a workable plan, and the eventual dam-burst impressive on the budget.

But the misgivings are not glossed over. There’s a dicey moment when it looks as if the kids, crawling all over the nurse, tearing off her clothes, are about to embark on mass juvenile rape. And the bloodlust will only be slaked when, by dint of secreting the detonators essential to the plan, they force Turner to lead them on a raid on the Germans, tossing hand grenades into houses and opening fire from the back of a truck on the unsuspecting enemy.

Aldo, in particular, gets a taste for killing and in a later battle doesn’t hold back when one of his comrades inadvertently gets in his way.

Sold as a junior edition of a mission picture, the trailer would have probably been enough to put off large sections of the audience, uncomfortable with kids being employed in such mercenary fashion. Kids grow up in war but not that fast seemed to be the general reaction. Okay if they’re portrayed as victims, less acceptable as gun-happy butchers.

So, the best elements of the movie is in not avoiding such misgivings. It was soon clear from the American experience – though this is not specifically alluded to – that hordes of kids in Vietnam were going down this route. The point at which kids cross over into bloody adulthood and lose the essence of childhood is dealt with too. That scene on the face of it and in isolation appears maudlin but in the context of the picture works very well. But the violence or its aftermath are not the most striking images. Again and again, the camera returns to the dirty, clothes-tattered, Bianca clutching the two infants, the detritus of conflict.

Setting aside his moustachioed muscle, Rock Hudson (Seconds, 1966) gives a well-judged performance and Sylva Koscina (A Lovely Way To Die, 1968), shorn of glamor, holds the emotional center. Mark Colleano (The Boys of Paul St, 1968) gives a vicious impression of a young hood on the rise. Directed by sometime cult director Phil Karlson (A Time for Killing, 1967) from a script by S.S. Schweitzer (Change of Habit, 1969) and producer Stanley Colbert. Great score from Ennio Morricone.

It’s worth pointing out that the idea of kids taking up arms received positive critical approval when it was applied to such an arthouse darling as If… (1969) but of course they were public schoolboys forced into action by bad teachers and in reaction to “the establishment” and not after seeing their families slaughtered. Double standards, methinks.

Worth reassessment.