Had things run according to the original plan, we could have seen Frank Sinatra return to a Communist country for the first time since The Manchurian Candidate (1962). But if you had wanted to write a script about the guy who wrote The Chairman, you couldn’t have invented a more interesting character than Samuel Richard Solomonick. He was one of those guy who held every job under the sun before reinventing himself as an anticommunist going by the name of Jay Richard Kennedy and subsequently entering the fields of real estate, radio and brokerage, then landing a gig managing Harry Belafonte and writing the screenplay for I’ll Cry Tomorrow (1955).

By the time he ended up as an executive at Sinatra Enterprises he had a couple of ideas to sell. Forming Jade Productions in 1966 with director Richard Quine (How To Murder Your Wife, 1965), the pair hooked Sinatra’s interest in two projects, Follow the Runner (which would have co-starred Sammy Davis Jr) and The Chairman plus William Holden eyeing the lead in The Wordlings about the population explosion.

Sinatra was known for falling out with directors, shunting Mark Robson off The Detective (1968), so whether Quine would have lasted the pace is anybody’s guess. After success with Tony Rome (1967), Twentieth Century Fox briefly toyed with the prospect of pairing Sinatra and new wife Mia Farrow in The Chairman. Originally scheduled to begin shooting on January 1967, that later shifted to early 1968. The notion that the movie also had parts for Spencer Tracy and Yul Brynner was one of those puff pieces that some journalists swallowed.

Despite some enticing projects – he was first name down to direct Catch 22, after Columbia had spent $150,000 buying the novel, and to helm the screen translation of Broadway hit The Owl and the Pussycat – Richard Quine’s career teetered after the flop of Hotel (1967). Making no headway with Sinatra he made instead another flop, Oh Dad Poor Dad (1967) and was effectively put on furlough for three years after failing to finance a movie to star Alex Guinness and Lee Radziwill.

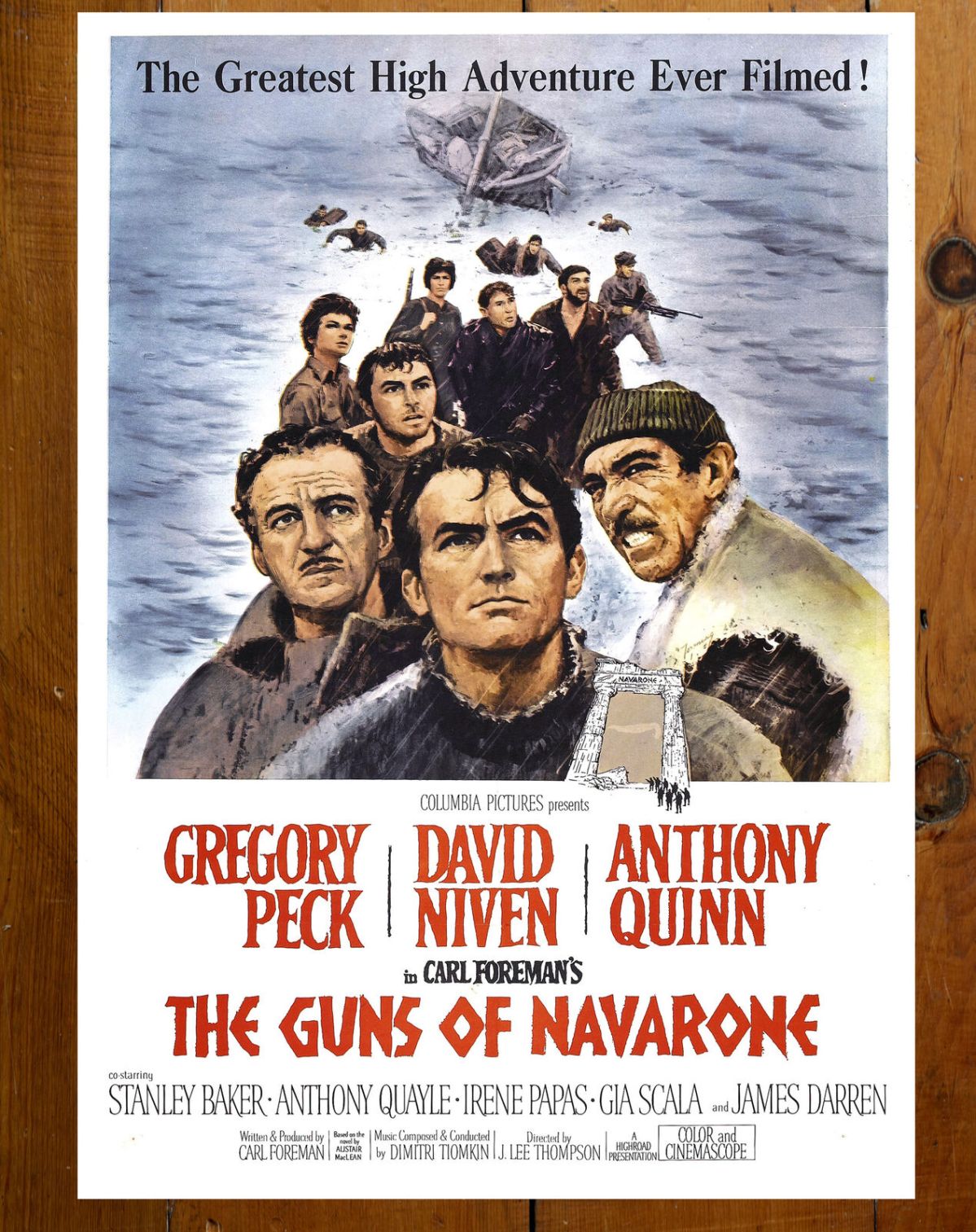

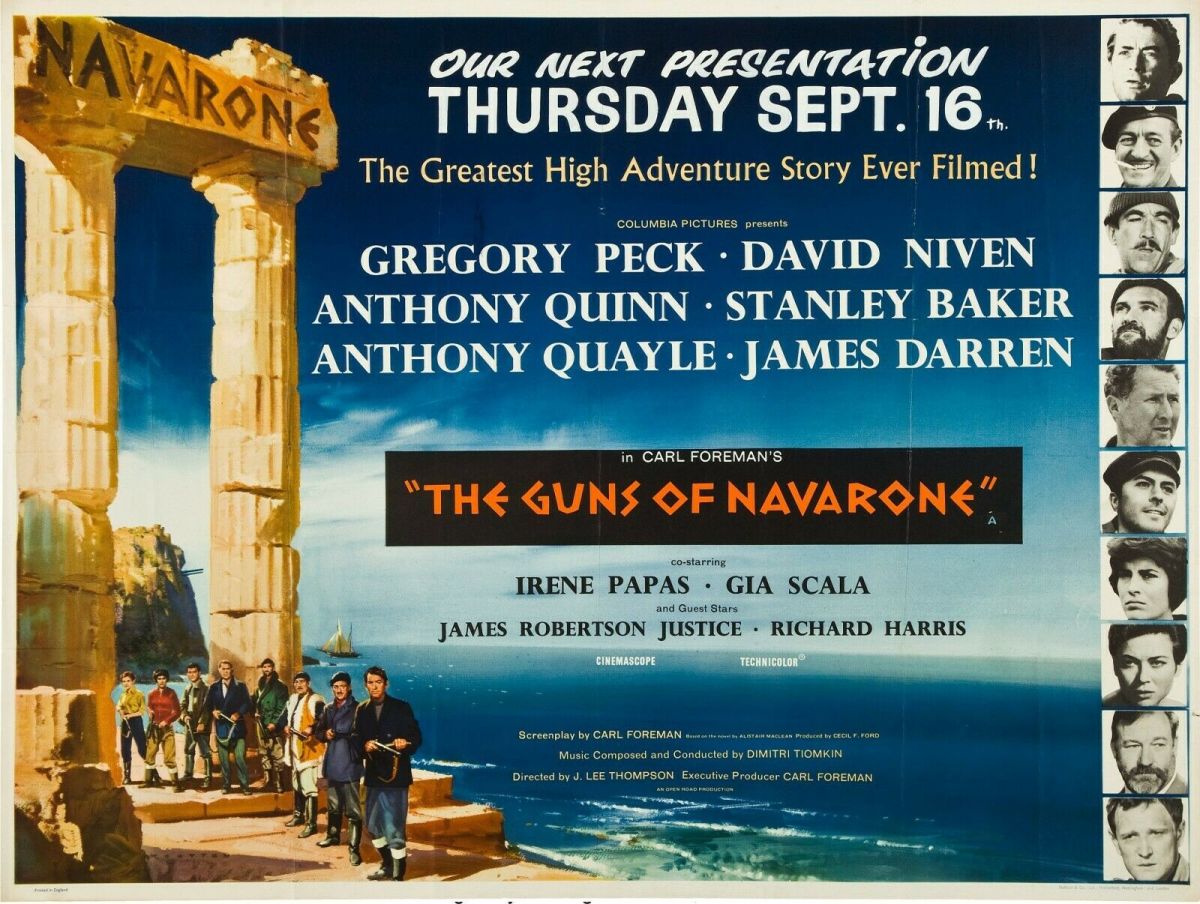

Quine exited The Chairman in May 1967 when former PR bigwig Arthur P. Jacobs took over the production and with Sinatra in absentia turned to British director J. Lee Thompson who had helmed the producer’s debut picture What a Way to Go (1964). And that proved a lucky break for Thompson who had yet to match the success of The Guns of Navarone (1961).

After successive flops – Return from the Ashes (1965) and Eye of the Devil (1966) – Thompson had plenty projects on the boil including a musical remake of Alexander Korda’s The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) with a score by Richard Rodgers and Peter Ustinov playing the lead. Also on his slate was High Citadel based on the Desmond Bagley bestseller; The Harp That Once for Columbia; an adaptation of James Clavell bestseller Tai Pan; a sequel to The Guns of Navarone called After Navarone that would reunite the director with star Gregory Peck and writer-producer Carl Foreman; and Planet of the Apes (1968) to which he and Jacobs held the rights.

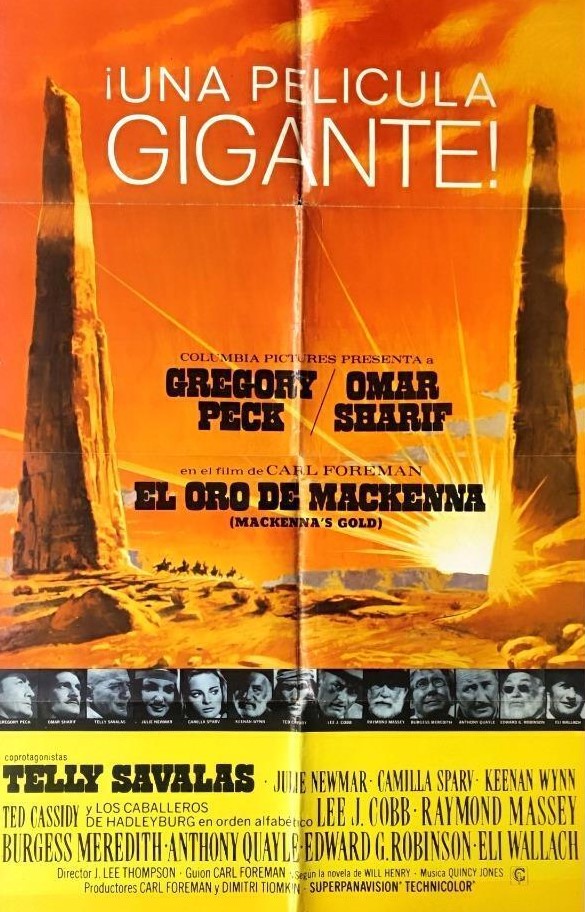

While none of these projects – except Planet of the Apes and minus Thompson – came to fruition, the Navarone connection would lead to Mackenna’s Gold for Foreman. In the meantime he had helmed a modest drama, Before Winter Comes (1968) starring Broadway star Topol. When Arthur P. Jacobs greenlit The Chairman, he hired Thompson who looked no further than Peck, connection re-established via the Navarone sequel. They were a four-time pairing – Cape Fear (1962) and Mackenna’s Gold and The Guns of Navarone. Peck was a controversial choice from the Twentieth Century Fox perpsective given he had broken a contract with the studio in 1960 to star in Let’s Make Love. But Jacobs smoothed ruffled studio feathers and paid his star $500,000 plus a percentage. With Jacobs on hands-on duty with Planet of the Apes (1968) – Mort Abrahams oversaw the production of The Chairman and immediately engaged in a budget dispute with the director. Jacobs had initially stipulated $4 million, Thompson believed he required another million. They didn’t quite split the difference, Fox had the film come in at $4.9 million.

Thompson recognized the problems of the script, pointing out that “the hardest thing for Americans about the film’s concept is accepting that China has some competent scientists.” Rather ingenuously, he averred that the movie would have “no political overtones,” while Abrahams retorted that it might have “some political overtones.” It would been obvious to anyone that a picture featuring Mao was bound to have political repercussions, his Little Red Book a massive bestseller on the campus, an album cut of recitations from the book and Edward Albee in 1968 premiering a play called Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung.

Denied access to China, the production team spent four months “reading everything we could get our hands on.” At one point they considered dropping the scene featuring Chairman Mao and lengthening the sequence relating to Peck’s arrival in Hong Kong. In any case, different versions of the Hong Kong environs were shot, some with nude shots of girls in a house of pleasure.

The British Colonial Office in Hong Kong blocked filming there after fears of riots due to the production daring to portray Mao Tse-Tung on screen. Taiwan substituted for China although the locals there were also incensed, so much so they burned an effigy of Peck. Wales, funnily enough, was another location as was London University. Filming began on August 28 and finished on December 3.

Although it might appear that Ben Maddow (The Way West, 1967) wrote his script based on Jay Richard Kennedy’s novel, in fact the novel appeared after the screenplay with Kennedy writing the novelizaton, and it’s more likely that what Maddow adapted was the original Kennedy screenplay. Interestingly enough, around this time Maddow had first crack at the Edward Naughton western novel that became McCabe and Mrs Miller (1971).

It wasn’t the first time Variety got a prediction wrong: “powerful box office attaction” fell far short of the actual results. This proved an annus miserabilis for Gregory Peck. In fact, he had four films, not three, released in 1969. By release date The Stalking Moon technically belonged to the previous year, but it only played a handful of cinemas in 1968, its general release taking place in 1969.

Despite pocketing a total of over $2 million, Peck’s marquee value was in clear decline. Of the Peck quartet, Marooned did best, placing 33rd on the annual box office chart, with $4.1 million. Mackenna’s Gold (31st) took $3.1 million in rentals (the amount returned from the gross once a cinema has taken its cut), The Stalking Moon (38th) on $2.6 million, and The Chairman (41st) with $2.5 million.

SOURCES: Gary Fishgall, Gregory Peck (Scribners, 2002) p267; James Caplan, Sinatra: The Chairman, (Doubleday, 2015), p724; “7 from 7 Arts,” Variety, March 3, 1965, p4; “Richard Quine,” Variety, July 7, 1965, p20; “Return of Advances,” Variety, October 6, 1965, p7; “Form Jade Prods,” Variety, December 15, 1965, p4; “J Lee Thompson Nearly Finished on 13,” Variety, February 2, 1966, p28; “Catch As Catch 22 Can,” Variety, February 23, 1966, p4; “Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Musical Henry VIII,” Variety, Mar 16, 1966, p1; “Inside Stuff – Pictures,” Variety, March 30, 1966, p22; “Lee Thompson Busily Blueprints His Musical Version of Henry VIII,” Variety, April 27, 1966, p17; “Jay Kennedy Script,” Variety, July 6, 1966, p5; “After Navarone,” Variety, April 19, 1967, p14; “Scripting Red Chinese,” Variety, May 21, 1967, p4; “”Personality Chemistry,” Variety, May 24, 1967, p4; New York Soundtrack,” Variety, Sep 20, 1967, p27; “Pat Hall Noel to Col,” Variety, December 27, 1967, p5; “N.Y. Indie Label Grooves Chairman Mao’s Thoughts,” Variety, April 10, 1968, p56; “Man About Town,” Variety, July 17, 1968, p68; “Jas Clavell to Roll Siege,” Variety, August 21, 1968, p7; “Thompson Wraps Up,” Variety, August 28, 1968, p29; “New York Soundtrack,” Variety, October 23, 1968, p18; “British Bar Fox’s Chairman,” Variety, December 4, 1968, p17; Big Rental Films of 1969,” Variety, January 7, 1970, p15; “Big Rental Films of 1970,” Variety, January 6, 1971, p11.