Has contemporary bite, given half the picture is about abortion, banned in Britain at that time and the Pill yet to come on-stream. Being a single mother was an equally unwelcome tag unless you were a widow, in which case you were shrouded with respectability.

Pregnant French lass Jane (Leslie Caron) has decided to hang on in Britain rather than face the shameful ordeal of returning home. She knows who the father is, Terry (Mark Eden), to whom she lost her virginity in a week-long affair in Cornwall, but she’s not planning to hustle him into a shotgun wedding and you get the idea that, at 27, her virginity was weighing heavily on her.

Ending up in a bedsit in London – the titular room a landlord’s clever way of turning one decent-sized room into two smaller ones, each with a share of the window – she is clearly au fait with a British legal loophole that permits termination should pregnancy damage her mental health. And there were enough Harley St doctors to mentor her through such a loophole, for a fee of course.

It’s the briskness of Dr Weaver (Emlyn Williams) that puts her off. She has another go, later on, this time with black market pills from one of her neighbors, but they don’t work. Meanwhile, she has fallen in love with aspiring writer Toby (Tom Bell) and divines, correctly, that he won’t want to bring up another man’s child. In the end, she has the baby and scarpers back to France to face the music.

On the face of it an ideal candidate for the “kitchen sink” mini-genre that was pervasive at the time, but actually much more rewarding than many of the genre with dealt with male anger. This is much more about acceptance, without being craven or abject about it.

And there’s much to enjoy in director Bryan Forbes’ understated style. Half the time you could imagine you were in noir from the use he makes of the commonplace manner in which lights in staircases generally went off after a minute or so (not so much an energy-saving device as a money-saving one for the landlord) and he makes clever play of these sudden changes. There are also, unusual for the time, disembodied voices – the camera on Jane as she mounts the stairs, the voice her out-of-sight landlady Doris (Avis Bunnage). And every now and then the camera glides from her room into that of her neighbor, jazz trumpeter Johnny (Brock Peters) who can hear everything through the paper-thin walls, her morning retching and her night-time love-making with Toby.

How Johnny does find out about her baby is beautifully done, the best sequence in the movie. She works in a café where Johnny eats each night and she’s set a little table for him with a flower in a bottle. But he doesn’t turn up. She suspects, for no real reason except the worst, that he’s in the basement making out with one of the sex workers, but it’s Johnny (who had always been a good friend) who tells her that, from a sense of his disgust, he has let her boyfriend know the truth.

Like Darling (1965), this is a fascinating portrait of a woman making the wrong decisions. But Jane lacks Diana’s power. She’s not helpless exactly, and certainly has a good line in getting rid of unwanted attention. Her motives are not entirely clear. She wasn’t in love with Terry and for a long time she fends off Toby. She deludes herself into believing that Toby’s love for her will overcome his distaste that she is carrying another man’s child. That’s when she takes the pills.

You could kind of get the impression, however, that the real reason for Jane’s predicament is so that the actress can follow in the footsteps of Greta Garbo, Katharine Hepburn et al to wallow in grief. But it’s more subtle than that. She hasn’t been thrown aside by a callous male. She had made a decision to lose her virginity without considering the consequences and now that there is consequence changes her mind in impulsive fashion on how to deal with it.

Surrounding this central tale are some snapshots of life in a tawdry rooming-house. Two of the occupants are gay, Johnny and faded actress Mavis (Cicely Courtneidge), the landlady has a succession of gentlemen friends, while in the basement Sonia (Patricia Phoenix) works as a prostitute.

Leslie Caron (Guns of Darkness, 1962) was nominated for an Oscar and won a Bafta and a Golden Globe. The film was nominated for a Bafta and a Golden Globe. Tom Bell (Lock Up Your Daughters!, 1969) is good as the struggling writer. And Brock Peters (The Pawnbroker, 1964) has a peach of a part.

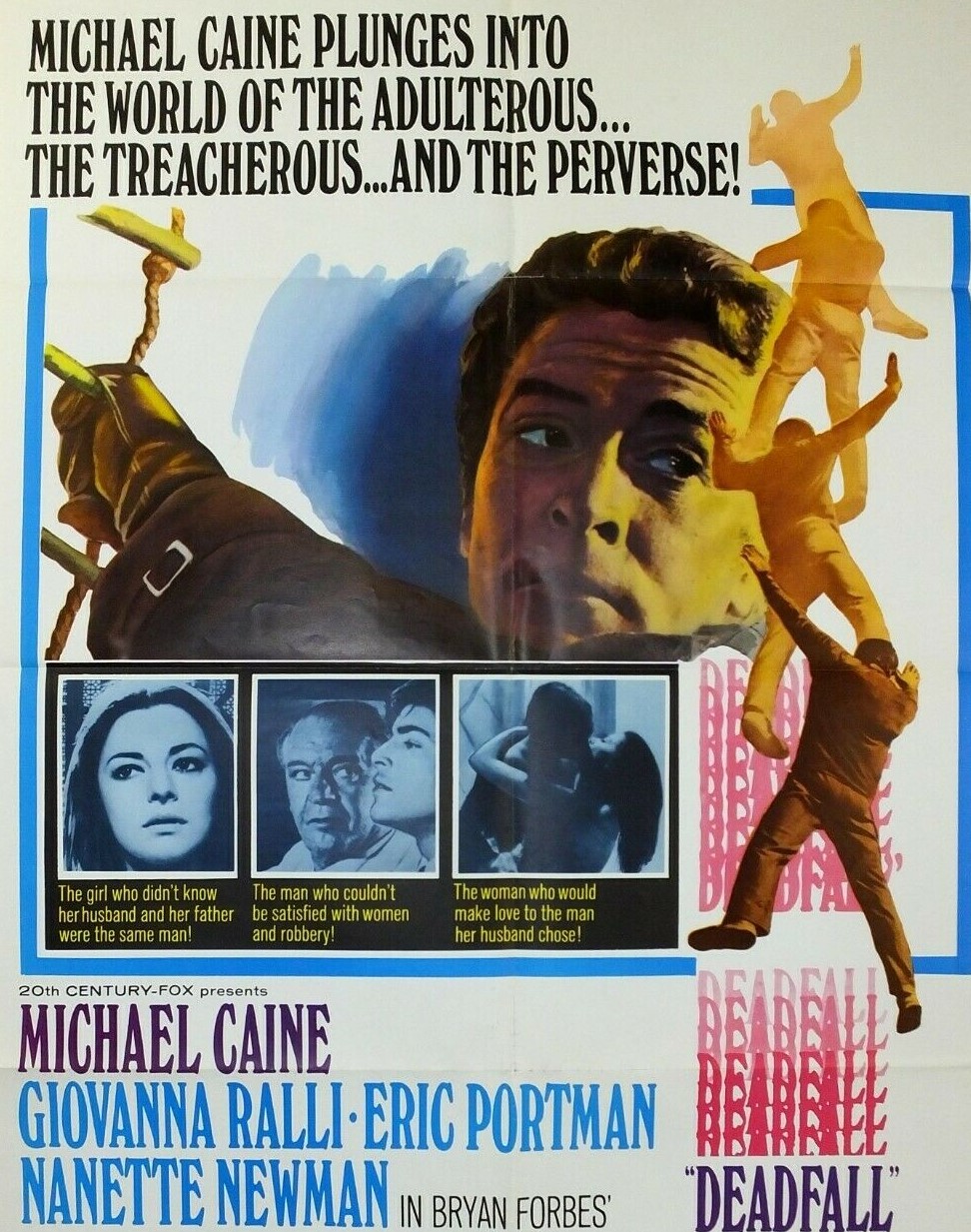

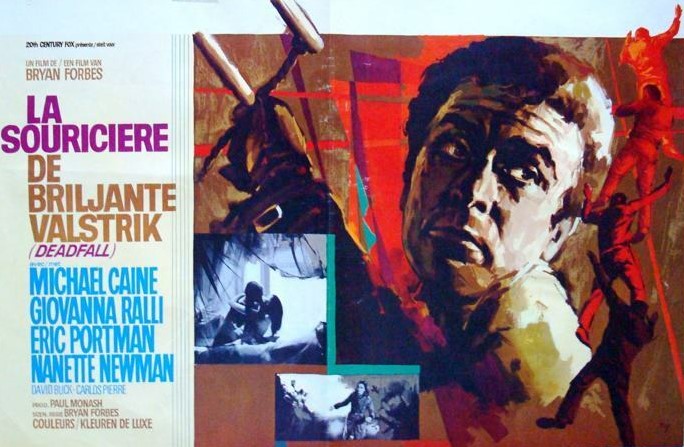

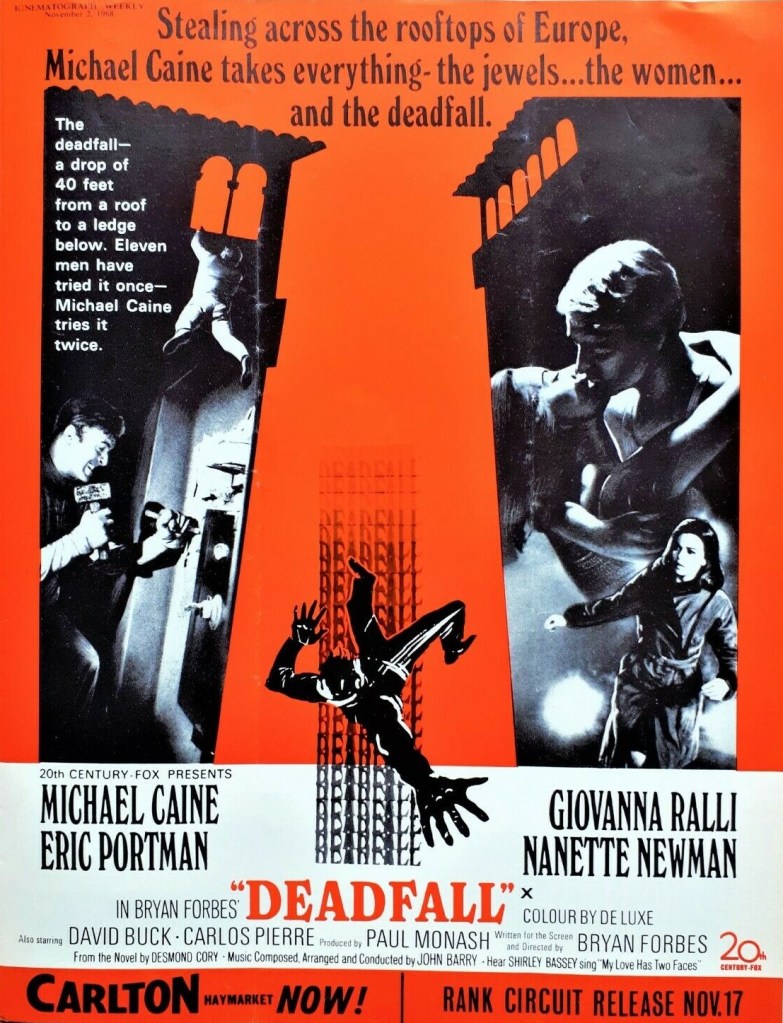

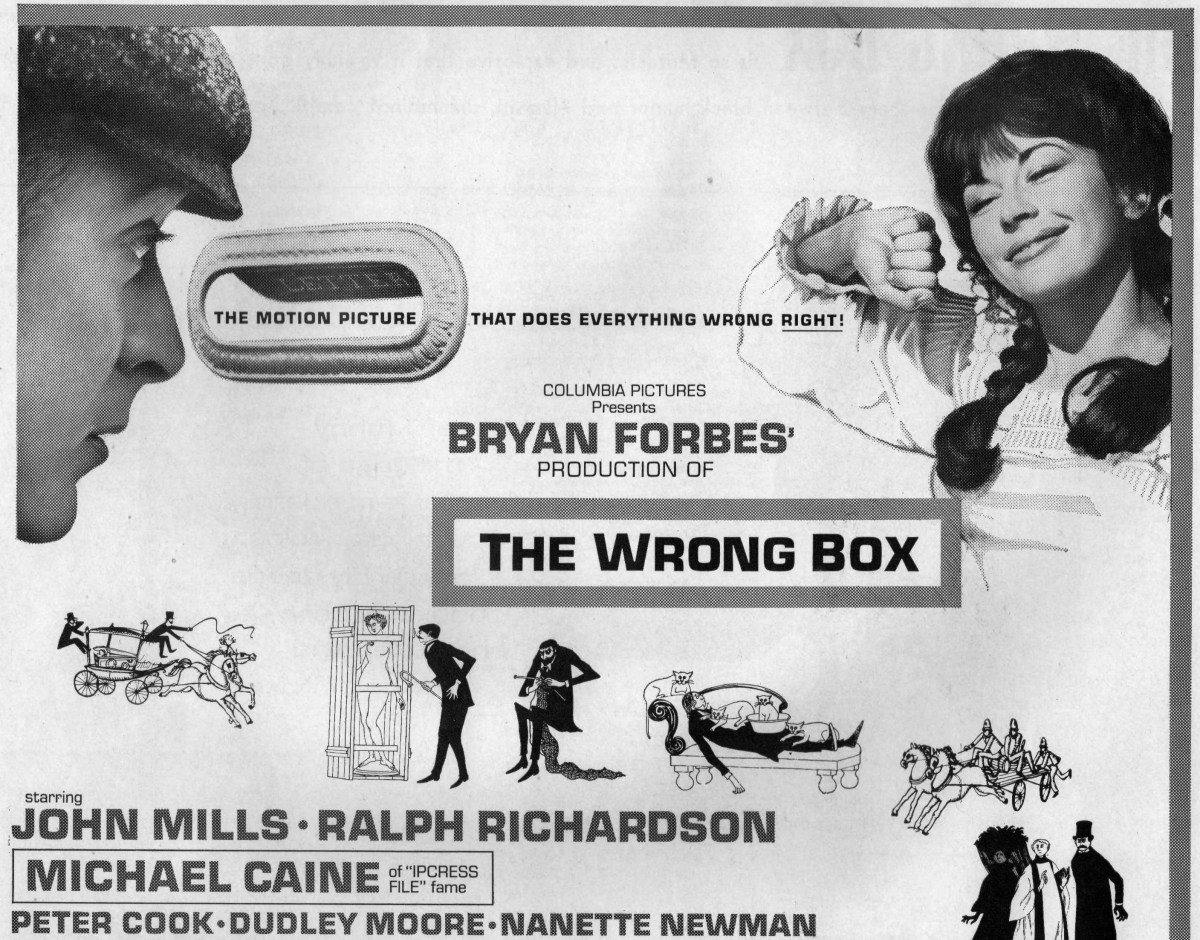

Director Bryan Forbes (Deadfall, 1968) wrote the script from the Lynne Reid Banks bestseller.