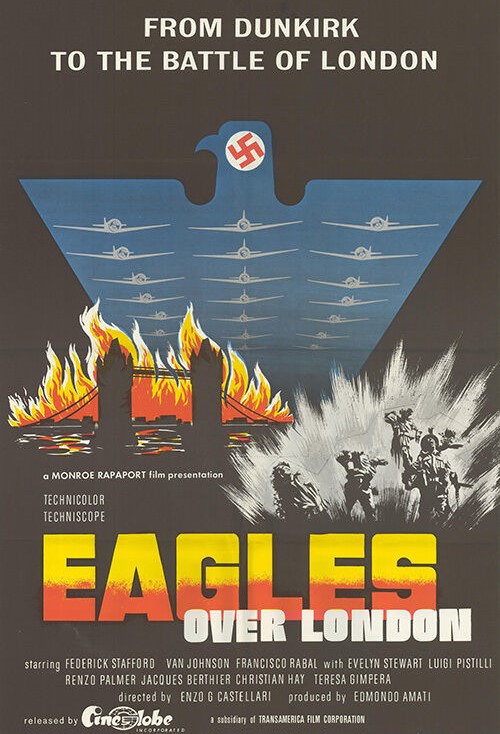

Presumably intended to capitalize on/rip-off the same year’s big-budget roadshow The Battle of Britain manages to cram in a pack of action beginning with a tank ambush in Normandy, the Dunkirk evacuation, the Battle of Britain, rooftop shoot-outs, ending up with an audacious attack of RAF High Command by a team of German saboteurs. As notable for technical achievement, split screen – sometimes split diagonally or quartered – in the manner of The Boston Strangler (1968) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), shots through various tiny holes, scenes filmed overhead, and a dazzling swirling camera sequence that would normally presage intimacy but here means death.

Somehow manages to squeeze a surprising number of dramatic moments focusing on relationships, a brief nod to homosexuality, and emulating Fraulein Doktor (1969) in giving the Germans credit for astute and effective espionage. Obvious use of stock footage for the air fight sequences, but you wonder what else has been cobbled out of the vaults given the preponderance of scenes requiring massive numbers of extras. Throw in Hollywood veteran Van Johnson (Divorce American Style, 1967) and a particularly good Cockney sergeant (Renzo Palmer) and it hardly lets up.

So, Captain Stevens (Frederick Stafford) heads up a unit delaying the German blitzkrieg in France in 1940. The Germans, led by Donovan (Francisco Rabal), meanwhile, are in disguise, assuming the identities of dead British soldiers with the intention of infiltrating Britain and destroying its radar installations. Inadvertently, Stevens saves Donovan’s life, thus giving the German accepted entry into British high command. Equally inadvertently Stevens allows the German access to his girlfriend Meg (Evelyn Stewart) who needs a shoulder to cry on. Donovan has his own girlfriend, Sheila (Teresa Gimpera) on tap, an undercover agent working as a barmaid, well-trained at collecting loose talk and seduction.

Elements of giallo keep popping up as the Germans need to embark on a murderous rampage to continue to acquire new identities to keep ahead of the pursuing investigation, one strangulation taking place in a gay sauna. Every now and then we pop into RAF High Command where Air Vice Marshal Taylor (Van Johnson) is helping thwart the German aerial attacks and in the end, since more bodies are required, elects to go into battle himself.

The small screen allows laughable moments – model airplanes crashing into the sea, cardboard radar installations toppling – to pass almost unnoticed since most of the rest of the action is well rendered, the rooftop scene especially, and the other various shoot-outs where – shock to the system – the British are constantly outwitted and outgunned.

Mostly, you’ll note how stylish a concoction this is given the low budget. Excellent sex scene against the background of exploding bombs, the duping of our hero by the enemy, and one terrific scene where Sheila is deemed surplus to requirements, calmly accepting her fate on condition that it’s her lover who pulls the trigger.

This would have been solid support material in English-speaking countries but most likely a main feature in its Italian homeland. Might have even done better if distributors waited until Afred Hitchcock’s Topaz (1969) appeared since he recruited Frederick Stafford as his leading man. Stafford was always under-rated but he keeps this afloat, though the Germans have the more interesting roles, especially Francisco Rabal and Teresa Gimpel. Evelyn Stewart (The Whip and the Body, 1964) has a smaller part.

Not content with introducing far more style and, shall we say, flamboyance, than the material might suggest director Enzo G. Castellari (Any Gun Can Play, 1967) has the audacity to end by using Winston Churchill’s “the few” speech to halt the traffic so the British lovers can catch up with each other.

A classic example of what an interesting director can do with what in other hands would be more mundane material. Not quite sure why it took five screenwriters.

Surprisingly fun watch overloaded with style.

REVIEWED PREVIOUSLY IN THE BLOG: Frederick Stafford in Topaz (1969), Evelyn Stewart in The Whip and the Body (1964), Van Johnson in Divorce American Style (1967).