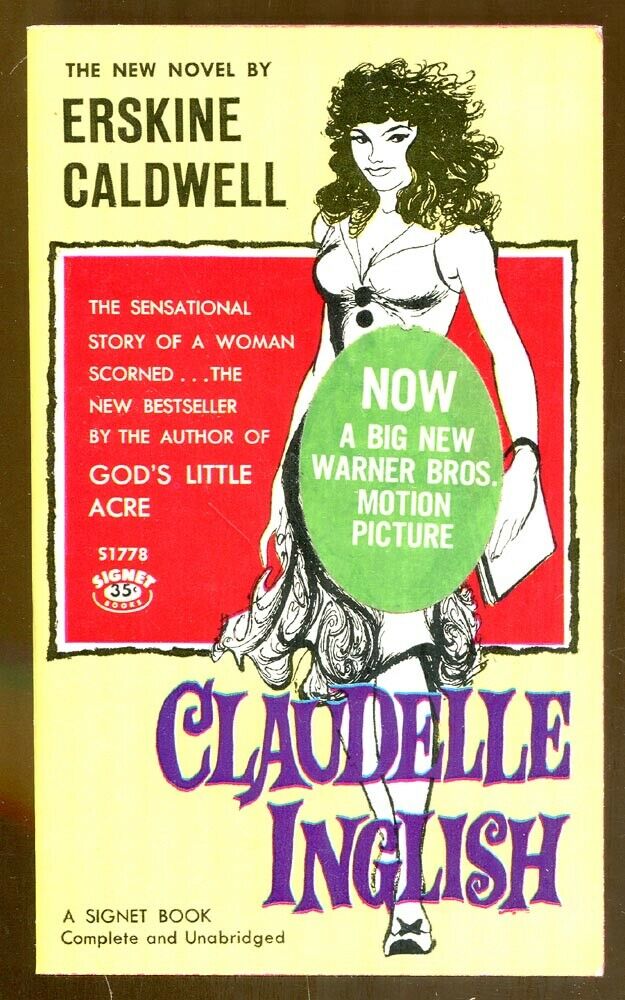

Simple small-town morality tale, brilliantly told, with a quiet nod to The Blue Angel and Citizen Kane. Shy dirt-poor farmer’s daughter Claudelle Inglish (Diane McBain) after falling for the handsome Linn Varner (Chad Everett) expects to be married when he returns from his Army stint until she receives a “Dear John” letter. Initially devastated, keeping all his letters and the dancing doll she had won with him at a fair, she decides that lying in bed all day and staring at the ceiling is not going to work. So she smartens up her frumpish look with lipstick and turns her simple wedding dress into a more attractive outfit.

She discovers that the boys are so desperate to come calling on this new-look creature that they will bring presents to every date, ranging from the biggest box of candy in the shop to a pair of red shoes. Encouraging her determined manhunt, dissatisfied mother Jessie (Constance Ford), who has endured twenty years of broken promises throughout marriage to hardworking Clyde (Arthur Kennedy), beseeches her to go after a rich man. Luckily, there is one in the vicinity, the widowed S.T. Crawford (Claude Akins) who happens to be their landlord. Crawford tries to bribe Clyde with free rent and other benefits to put in a good word, but to no avail, the father believing that true love cannot be bought and, furthermore, will alleviate abject poverty.

of the key dates on the U.S. release calendar.

Claudelle bluntly rejects Crawford as “too old and too fat” but takes his present anyway and, under pressure, agrees to go for a ride with him without allowing him to stop the car. Dennis Peasley (Will Hutchins), elder son of a store owner, believes he is the front runner, deluging her with gifts, naively believing she is his sweetheart until he realizes he is in competition with a horde of other local boys, including his younger brother, and outsider Rip (Robert Colbert). Jessie, seeing the prospect of a rich husband slip away, embarks on an affair with Crawford. Soon, Claudelle has the entire male population in the palm of her hand, piling up presents galore. However, tragedy, in the way these things go, is just round the corner.

What struck me first was the subtlety. Nothing here to bother the censor, beyond the immorality on show and despite Hitchcock breaking all sorts of sexual taboos with Psycho the year before. This isn’t an all-hot-and-bothered essay like the previously reviewed A Cold Wind in August or a picture that pivots on twists-and-turns like A Fever in the Blood, both out the same year. It is so delicately handled that took me a while to work out that Claudelle was actually having sex with all these guys.

The initial shy girl blossoming under the first blush of love is done very well, a gentle romance ensuing, Claudelle still withdrawn in company, agreeing to an engagement even though Linn cannot afford a ring, waiting anxiously for his letters, adoring the dancing doll, paying off a few cents at a time material for a wedding dress. It’s only after she receives a Dear John (Dear Jane?) letter that it becomes clear, though not crystal clear, that sex has been involved because that word is never spoken and that action never glimpsed. Only gradually do we realise that present-givers are being rewarded, and as her self-confidence grows she is soon able to pick her own presents. One look is generally all it takes to have men falling all over themselves to give her what she wants, which is, essentially, a life where promises are not broken. But the closest she gets to showing how much she is changed from her original innocent incarnation is still by implication, telling a young buck she is “pretty all over.”

I was also very taken with the black-and-white cinematography by Ralph Woolsey. The compositions are all very clear, but in the shadows Claudelle’s eyes become glittering pinpoints. The costumes by Howard Shoup won an unexpected Oscar nomination, his third in three years. Veteran director Gordon Douglas (Them!, 1954) does an excellent job of keeping the story simple and fluent, resisting all temptations to pander to the lowest common denominator while extracting surprisingly good performances from the cast, many drawn from Warner Brothers’ new talent roster.

Diane McBain (Parrish, 1961) handles very well the transition from innocence to depravity (a woman playing the field in those days would be tagged fallen rather than independent) and holds onto her anguish in an understated manner. In some senses Arthur Kennedy (Elmer Gantry,1960) was a coup for such a low-budget production, but this could well have been a part he was born to play, since in his movie career he knew only too well the pain of promise, nominated five times for Best Supporting Actor (some kind of record, surely) without that nudging him further up the billing ladder. His performance is heartbreaking, working his socks off without ever keeping head above water, repairs getting in the way of promises made to wife and daughter, kept going through adoration for his wife.

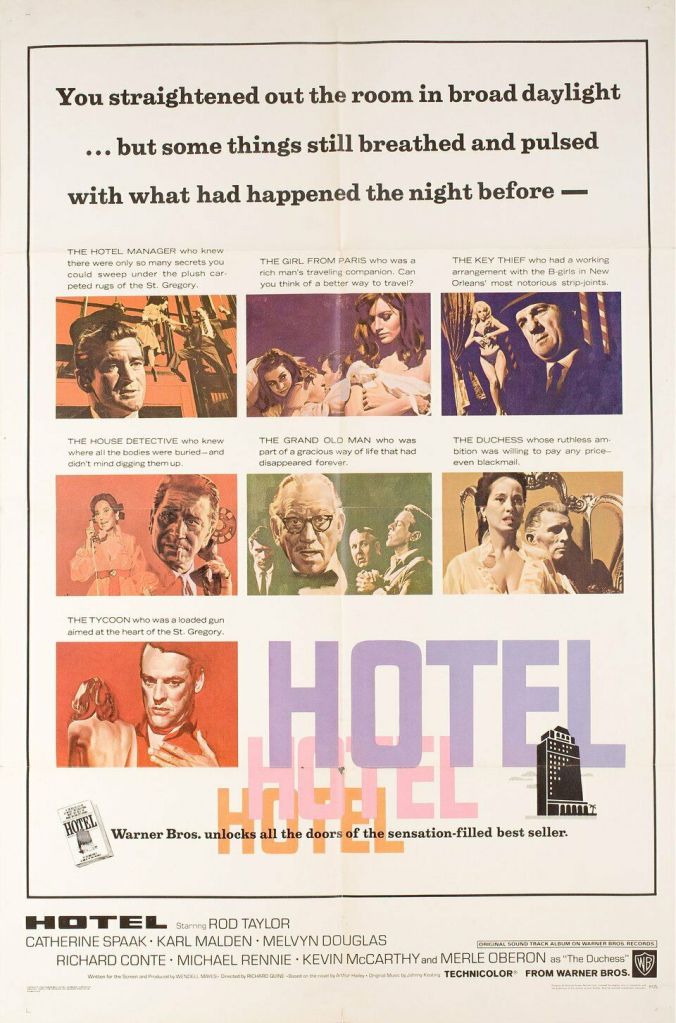

Constance Ford (Home from the Hill, 1960) is heartbreaking in a different way, scorning her loving husband and dressing like her daughter in a bid to hook Crawford. Television regular Claude Akins is the surprise turn. In a role that looked like a cliché from the off – i.e. older powerful man determined by whatever means to win the object of his desires – he plays it like he was auditioning for The Blue Angel, hanging on every word, being twisted round her little finger, demeaning himself as he is made to wait, sitting downcast outside the Inglish house like an rejected schoolboy. Of the younger cast, Will Hutchins was Sugarfoot (1957-1961), Chad Everett was making his movie debut, and Robert Overton had appeared in A Fever in the Blood (1961). Leonard Freeman (Hang ‘Em High, 1968) wrote the screenplay based on the Erskine Caldwell bestseller.

And where does Citizen Kane come into all this? The dancing doll Claudelle won at a fair when dating Linn is something of a motif, never discarded, as if a symbol of her innocence, and in close-up in the last shot of the film.