Unusually timely in today’s MeToo era, the 10-page A3-size Pressbook had a warning for young actresses 60 years ago about the sex predators operating in Hollywood. On the subject of “coping with an amorous male,” star Diane McBain commented: “The first months in Hollywood are likely to be dreadfully discouraging to any girl trying to gain a foothold as an actress. She needs an older person in whom she can confide.” In other words, get yourself a chaperone to fend off the men.

This was somewhat at odds with the tone of the film itself, which suggested that Claudelle Inglish was a male magnet.

The marketing team took the easy way out in selling this picture. Sleaze was the hook with copy lines and images as the big come-on. Pick of the copy lines: “When she was seventeen there wasn’t a man she’d let near her…When she was eighteen there wasn’t one she’d keep away.” More in keeping with the actual film was: “She liked boys looking at her…and thinking…and then she’d take her delicious kind of revenge on them all!”

The promotional people did not have much else in the way of ideas, beyond a glamor portrait of star Diane McBain as a means of stimulating a newspaper poll under the title “The Screen’s Most Beautiful Woman?” Another idea was a contest to list movie titles comprising a female name such as Mildred Pierce, Gigi etc. Probably the most original notion was a tie-up with a shoe store since the film’s main character had a predilection for red shoes.

Otherwise the emphasis was on the provocative. Exhibitors were encouraged to use a sidewalk stencil of the “voluptuous young girl” or arrange a lobby display of all the gifts Claudelle had received from her suitors. Slightly more complicated was getting restaurants involved in a contest where the letters of the character’s name could be used to part-spell out the titles of Erskine Caldwell books.

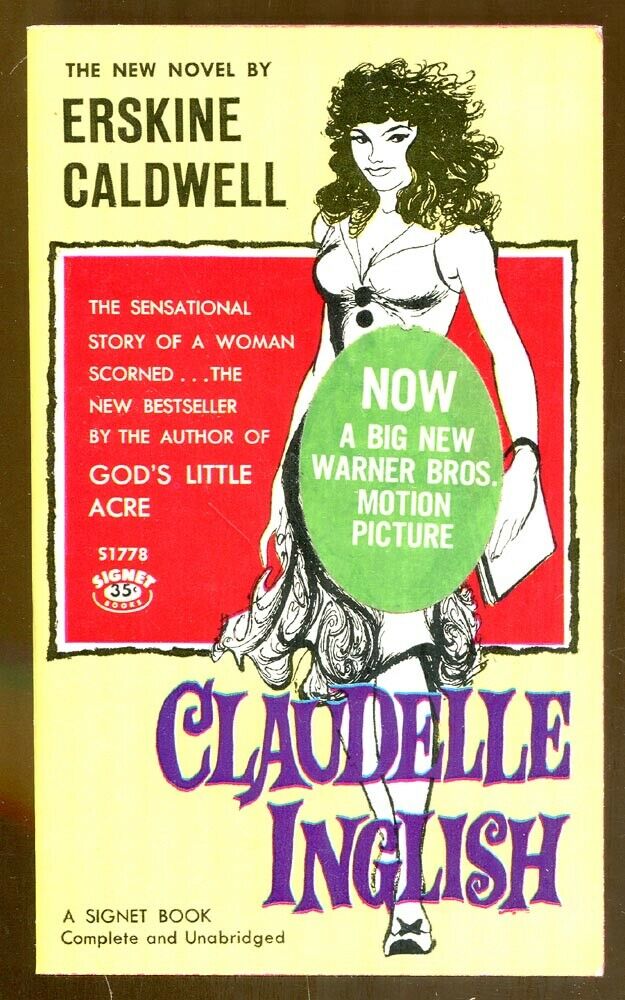

Author Erskine Caldwell, the all-time best-selling writer in America at that point with 41 million copies in print, was another big selling point. He had also authored other steamy yarns like God’s Little Acre and Tobacco Road and another 36 books besides so his novels were likely to command prime space in a bookstore. Signet had printed a movie tie-in edition that would go on sale in 100,000 outlets.

In terms of star push, the Pressbook concentrated on Diane McBain, promoted as a newcomer, despite having already appeared in Ice Palace (1960) and Parrish (1961) and with an ongoing role in television series Surfside 6 (1960-1962). Exhibitors were informed that McBain had “soared to stardom in little more than a year.” But also that her legs had given her a “big lift up the ladder of stardom” with several scenes revealing those attributes. McBain was only 20 at the time of the film’s release, born in 1941 in Cleveland, Ohio, but already earning money as a model at college. A Warner Brothers talent scout had spotted her on a modelling assignment which led to a role as the grand-daughter of Richard Burton in Ice Palace.

At the other end of the fame ladder, five-time Oscar nominee Arthur Kennedy appeared content to acknowledge that he was “rarely recognized in public” and if so was usually mistaken for someone else. Constance Ford, who played his wife in the picture, had already been paired with the actor three times, previously, twice on stage – Death of a Salesman and See the Jaguar – and in A Summer Place (1959).

There is a sad postscript to this which was pointed out to me by one of my readers. Sexual assault on women is not restricted to the movie industry. In 1982, Diane McBain was raped and attacked in her garage on Christmas Day after she had returned from a party. The culprits were never found. And although she began a second career as a rape victim counselor, she told the Los Angeles Times eight years later: “The shock of what happened caused loss of memory, inability to concentrate and I’m still startled out of all proportion.” (Gerald Peary, “In Search of…Diane McBain,” LA Times, May 27, 1990, 23).