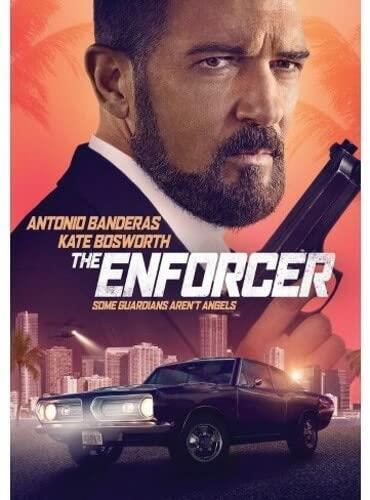

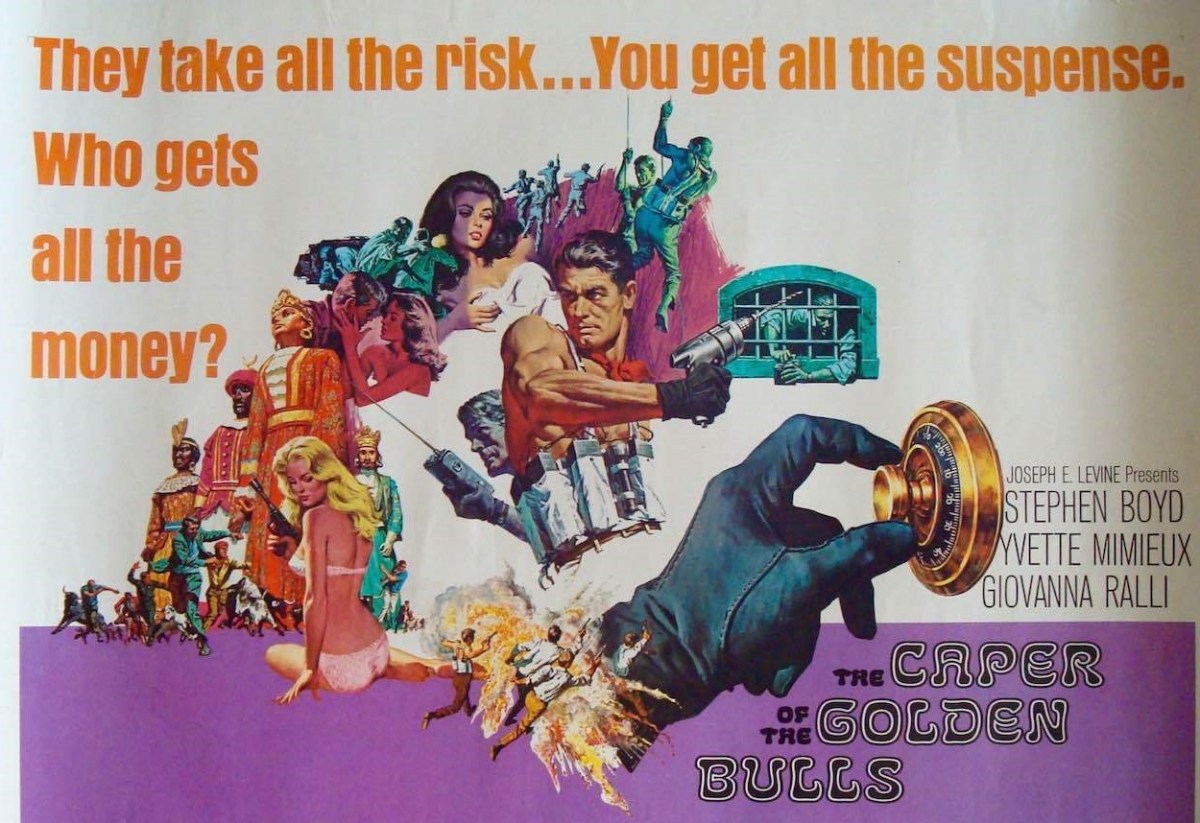

After pulling double worthy duty with Empire of Light and Till as the starting points for my Monday multiplex triple bill it was something of a welcome relief to finish with an unpretentious pretty serviceable actioner that traded on Taken, The Equalizer and The Mechanic.

Ex-con Cuda (Antonio Banderas) has taken up his old job of debt collector/enforcer for bisexual mob boss Estelle (Kate Bosworth). Through happenstance he acquires streetfighter protégé Stray (Mojean Aria). Cuda’s daughter won’t speak to him so he’s partial to coming to the aid of homeless 15-year-old Billie (Zolee Griggs). To get her off the streets he puts her up in a motel. But, of course, no good deed goes un-punished and the motel manager arranges for her kidnap by Freddie (2 Chainz), a rising gangster who threatens Estelle’s dominance.

Meanwhile, Stray falls for dancer/hooker Lexus (Alexis Ren) who works for Estelle and may well be her main squeeze, though the consensuality of that relationship may be in question.

There’s none of the pavement-pounding hard-core detective work or even nascent skill undertaken by the likes of Taken’s Bryan Mills before Cuda tracks down Billie’s whereabouts and it doesn’t take long for the various strands to coalesce, resulting in a variety of fights and shootings. Given it’s a perky 90-minutes long, there’s very little time for subplots anyway or to find deeper meaning. That’s not to say there aren’t patches of clever dialog – Estelle compares the blood in her veins to that of the marauders in ocean depths whose blood has evolved to be extremely able to withstand parts of the sea where the sun never shines. (She says it a bit neater than that).

And there’s no time wasted on sentimentality either. Neither Cuda’s ex-wife or daughter want anything to do with him and thank goodness we’re spared a scene of him emerging from jail with nobody to greet him. The movie touches on the most venal aspects of modern crime, paedophilia, webcam pornography, kidnap, sexual violence, and of course Freddie bemoans the fact that Estelle is so old-fashioned she wants her tribute paid in cash not cryptocurrency.

It’s straight down to brass tacks, Cuda not seeing the betrayal coming. Thanks for bringing me fresh blood, Cuda, says Estelle, would you like one bullet or two with your retiral package. The only element that seems contrived at the time, that the battered and bloodied Stray can fix Cuda’s broken down car, actually turns into a decent plot point. And where Bryan Mills seems to be living on Lazarus-time, here it’s clear that the ageing Cuda is not going survive these endless beatings and shootings, so if there’s going to be a sequel it will be on the head of Stray.

I had half-expected Antonio Banderas (Uncharted, 2022) to sleepwalk through this kind of good guy-tough guy role but in fact his mostly soft-voiced portrayal is very effective, and his occasional stupidity lends considerable depth to the character. Kate Bosworth (Barbarian, 2022) has been undergoing a transition of late and is very convincing as a smooth, if distinctly evil, bisexual gangster.

I’ve never heard of Mojean Aria though if I’d kept my ear closer to the ground I might have ascertained he was a Heath Ledger Scholarship recipient. He had a small role in the misconceived Reminiscence (2021) and took the lead in the arthouse Kapo (2022). Judging on his performance here, I’d say he is one to look out for. He has definite screen presence, action smarts and can act a bit too.

And just to show my ignorance I was unaware that Alexis Ren is one of the biggest influencers in the world. This is her second movie and she doesn’t really have much of a part beyond compromised girlfriend. Zolee Griggs (Archenemy, 2020) is another newcomer. But you remember that old Raymond Chandler saying that when the plot sags have a man come through the door with a gun. Well, here, there’s a different twist – it’s a woman, in fact both these women turn up trumps when it comes to rescuing the guys.

This is the directing debut of Aussie commercials wiz Richard Hughes and, thankfully, there’s none of the flashiness than would have drowned a tight picture like this. He keeps to the script by W. Peter Iliff who’s been out of the game for some time but who you may remember for Point Break (both versions), Patriot Games (1992), Varsity Blues (movie and TV series) and Under Suspicion (2000).

Undemanding action fare, for sure, but still it delivers on what it promises. It doesn’t have a wide enough release or a big enough marketing budget to even qualify as a sleeper but I reckon it will keep most people satisfied. I had thought this might be DTV but that’s not so. Although it’s not been released in the States it’s had a wide cinema release in Europe. However, this looks like it’s already on DVD but been thrown into cinemas to coincide with the launch of Puss in Boots.