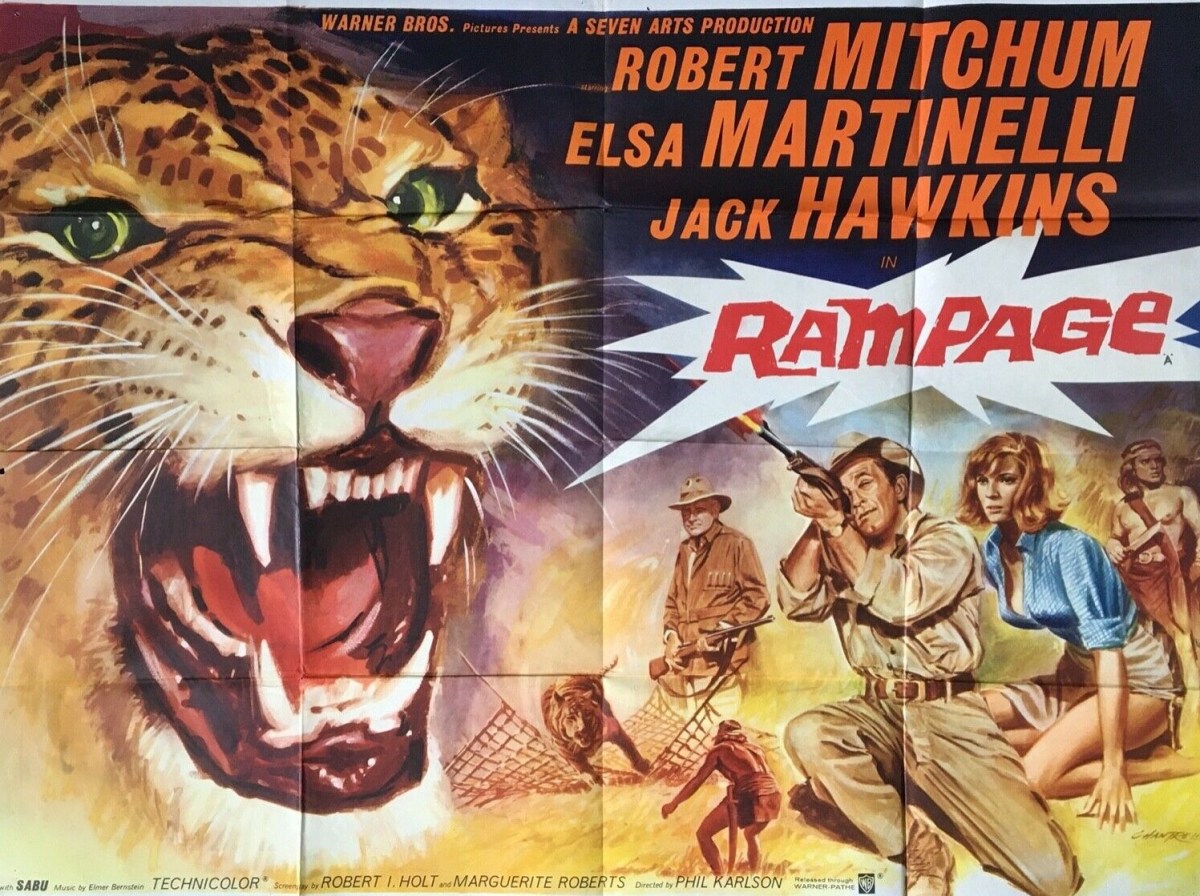

A more misleading title you’d struggle to find. There’s no sign of a rampage until the last 20 minutes, and even then it plays out on a rooftop in a city. Not a patch, action-wise, on Howard Hawks’ Hatari! the previous year, but sharing the female lead Elsa Martinelli. More romantic drama than jungle adventurer, and not much Malaysian jungle at that given Hawaii was the stand-in.

Big on metaphor, women viewed as trophies to boost the male ego or requiring male protection. Surprisingly contemporary with reference to the grooming of young women. Though Hatari! went down the same line, hunting animals for zoos rather than sport, this again take contemporary approach, animal conservation seen as a battle of cultures, between men for whom shooting an elephant or a rhino reinforces their macho tendencies, and those who want to preserve rare wildlife for future generations.

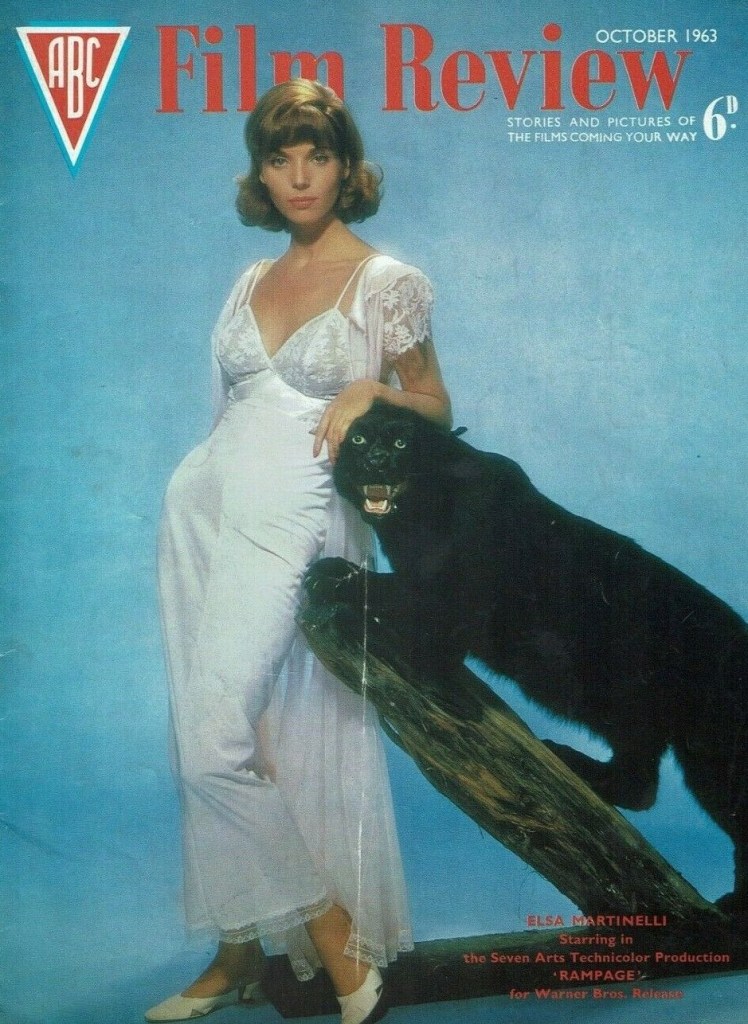

Trapper Harry (Robert Mitchum) and hunter Otto (Jack Hawkins) team up to capture for a German zoo two tigers and a legendary panther-like creature known as “The Enchantress.” From the outset, sexual tension sizzles between Harry and Otto’s young partner Anna (Elsa Martinelli). Although Otto is possessive, he permits Anna to take male companions on the assumption that she will always return to him.

Anna’s not quite as submissive as Otto would like to believe and she puts Harry in his place more than once. There’s a 35-year age difference between Otto and Anna. But Harry is disturbed at how they became lovers, persistently asking how soon, after the older man saved the orphaned girl from poverty, he seduced her.

The love triangle is set against a more primitive background where women have no rights and are as likely to be offered up to any passing male. Native guide Talib (Sabu) feels duty-bound to pass his wife onto to Harry. The wife not only acquiesces, but is insulted when the American refuses.

The men represent different cultures, Otto a marksman who prefers to bring his trophies back dead, hanging his virility on every scalp, Harry more emancipated for whom capture is enough. There’s a stand-off with a local tribe when Otto is too hasty with his rifle.

more of a leopard with some red marks.

Given the lack of budget and the consequent lack of action, it’s no surprise that the drama revolves around whether Anna will betray her lover. Despite his apparent laid-back approach, Otto watches Anna with an obsessive eye, her potential loss deemed a blow not just to his esteem but a sign of approaching death.

What sets this aside from the submissive female trope is that the decision rests with Anna. Harry certainly doesn’t push his luck and until his pride is dented Otto allows the situation to play out. The shift in Anna’s feelings is discreetly rather than dramatically handled. The traditional bathing scene is used to reveal that Anna is not actually married and therefore neither committing adultery nor under legal obligation.

When we finally get down to some action, the build-up is interesting, Harry using beaters to nudge tigers towards his traps, but, unfortunately the majority of these animals are a disgrace to their wild forefathers, on the whole appearing pretty obliging if not outright dumb. There’s one charging rhino and, heaven forfend, Otto commits the cardinal son of requiring two bullets to finish it off.

The movie picks up when they encounter “The Enchantress,” by a long way the smartest beast in this particular animal kingdom, who enhances her mythical status by hiding in a cave, clash of personalities between the alpha males triggering the movie’s final, more dynamic, phase, Anna coming into her own not just as a crack shot but as an independent woman, Otto making Harry his prey.

More interesting as an examination of contemporary mores, not quite as sexist as initially it appears, and nudging in the direction of a woman attempting to attain independence, and in discussing the issues surrounding conservation. Just as bold is the questioning of Otto’s motivation is saving Anna from poverty, an act of kindness or grooming? You might wonder how much better off Anna would be with a man two decades older rather than one three decades older, but nobody goes there.

The acting is uniformly under-played. Elsa Martinelli is given a better showcase for her talents here than in Hatari! and this is Robert Mitchum (Five Card Stud, 1968) at his laid-back best while Jack Hawkins (Masquerade, 1965) keeps his simmering under control until the end.

Without the budget to ape Hatari! director Phil Karlson (The Secret Ways, 1961) has no option but to focus on characters rather than animals, but finds interesting ways to put various messages across. Marguerite Roberts (Five Card Stud) and Robert I. Hope (White Commanche, 1968) based their screenplay on the novel by Alan Caillou a.k.a Alan Lyle-Smith.