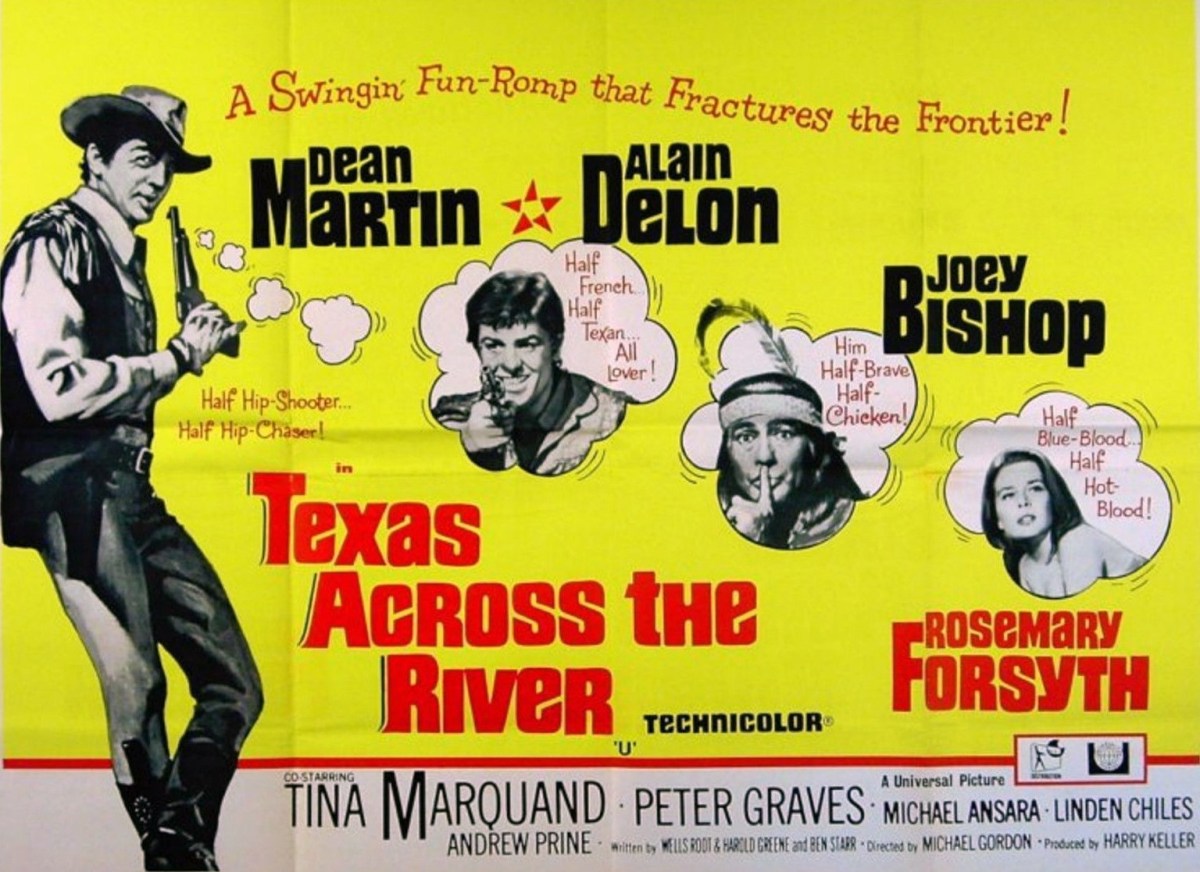

Excellent comedy western mixing dry wit and occasional slapstick to joyous effect. The wedding between Spanish duke Don Aldrea (Alain Delon) and Louisiana belle Phoebe (Rosemary Forsyth) is interrupted by her previous suitor Yancy (Stuart Cottle) who is killed in the resulting melee. Escaping to Texas, Don Aldrea’s marksmanship leads settler Sam (Dean Martin) to recruit him to help fight raiding Comanches. Romantic entanglement ensues when the Don rescues Native American Lonetta (Tina Marquand) and Sam has more than a passing interest in Phoebe.

It is so tightly structured that nothing occurs that doesn’t have a pay-off further down the line. Bursting with terrific lines – including a stinger of a final quip – and set pieces, it pokes fun at every western cliché from the gunfight, the cavalry in hot pursuit, and fearsome Native Americans to the snake bite and the naked bathing scene. Incompetence is the order of the day – cavalry captain Stimpson (Peter Graves) issues incomprehensible orders, chief’s son Yellow Knife (Michael Linden) cannot obey any.

The Don, with his obsession with honor and his tendency to kiss men on the cheeks, is a comedy gift. Despite his terrific head of hair, he is stuck with the moniker “Baldy” and every time he is about to save the day he manages to ruin it. Sam is the kind of guy who thinks he is showing class by removing his spurs in bed while retaining his boots. His sidekick Kronk (Joey Bishop), a mickey-take on Tonto, mostly is just that, a guy who stands at the side doing nothing but delivering dry observations.

Lonetta is full of Native American lore and has enough sass to keep the Don in his place. “What is life with honor,” he cries to which she delivers the perfect riposte, “What is honor without life?” Phoebe is a hot ticket with not much in the way of loyalty.

Two sequences stand out – the slapping scene (whaat?) and a piece of exquisite comedy timing when Sam, Phoebe and the Don try an iron out a complicated situation.

Good as Dean Martin (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) is the picture belongs to Alain Delon (Once a Thief, 1965) and I would argue it is possibly his best performance. Never has an actor so played against type or exploded his screen persona. Delon was known for moody, sullen roles, cameras fixated on his eyes. But here he is a delight, totally immersed in a role, not of an idiot, but a man of high ideals suddenly caught up in a country that is less impressed with ideals. If he had played the part with a knowing wink it would never have worked.

Martin exudes such screen charm you are almost convinced he’s not acting at all, but when you compare this to Rough Night in Jericho it’s easy to see why he was so under-rated. Joey Bishop (Ocean’s 11) is a prize turn, with some of the best quips. Rosemary Forsyth (Shenandoah, 1965) is surprisingly good, having made her bones in more dramatic roles, and Tina Marquand (Modesty Blaise, 1966) more than holds her own. Michael Ansara (Sol Madrid, 1968) played Cochise in the Broken Arrow (1956-1958) television series. Under all the Medicine Man get-up you might spot Richard Farnsworth. Peter Graves of Mission Impossible fame is the hapless cavalry leader.

Director Michael Gordon (Move Over, Darling, 1964) hits the mother lode, the story zipping along, every time it seems to be taking a side-step actually nudging the narrative forward. He draws splendid performances from the entire cast, knowing when to play it straight, when to lob in a piece of slapstick, and when to cut away for a humorous reaction, and especially keeping in check the self-indulgence which marred many Rat Pack pictures – two of the gang are here, Martin and Bishop. There’s even a sly nod to Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns when the electric guitar strikes up any time Native Americans appear. Frank De Vol (Cat Ballou, 1965) did the score. Written by Wells Root (Secrets of Deep Harbor, 1961), Ben Starr (Our Man Flint, 1966) and Harold Greene (Hide and Seek, 1964).

Terrific fun.