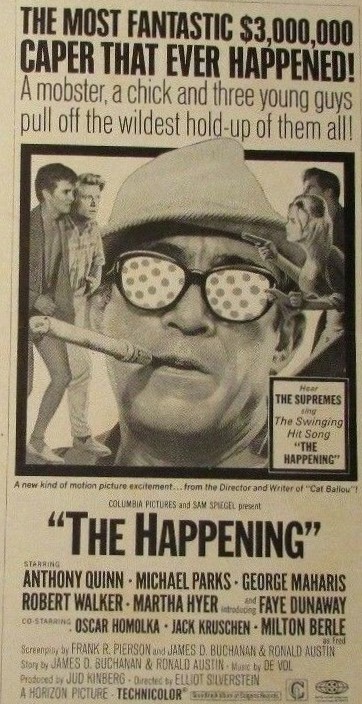

Poor casting blows a hole in this picture’s great premise and only an excellent turn by Anthony Quinn as an indignant kidnappee prevents it achieving “so-bad-it’s-good” infamy. In fact for the first third of the movie you could pretty much guarantee it’s going to be a stinker, so dire are the performances of the quartet of hippy kidnappers. Only when the camera cuts Quinn a bit more slack and the script skids into a clever reversal does the movie takes flight although still hovering dangerously close to the waterline.

Faye Dunaway (Sandy), all blonde hair and pouting lips, looks for the most part as though she has entered an Ann-Margret Look-A-Like Competition. Michael Parks (Sureshot) resembles a fluffy-haired James Dean. George Maharis is condemned to over-acting in the role as ringleader Taurus while Robert Walker Jr. as Herby does little more than mooch around. None shows the slightest spark and behave virtually all the time as if they are in on the joke.

For no special reason, beyond boredom, they kidnap hotel tycoon Roc (Quinn) hoping to make an easy score with the ransom. Unfortunately for Roc, none of those he is counting on to cough up the dough – wife Monica (Martha Hyers), current business partner Fred (Milton Berle), former business partner Sam (Oscar Homolka) and offscreen mother – will play ball. In fact, Monica and Sam, enjoying an affair, would be delighted if failure to produce a ransom ended in his death.

Eventually, while the movie is almost in the death throes itself, Roc fights back, using blackmail to extort far more than the kidnappers require from his business associates and taking revenge on his wife by setting her up as his murderer. It turns out Roc is a former gangster and well-schooled in the nefarious. So then we are into the intricacies of making the scam work, which turns a movie heading in too many directions for its own good into a well-honed crime picture.

Quinn is the lynchpin, and just as well since the others help not a jot. From a kidnappee only too willing to play the victim in case he endangers wife and son, he achieves a complete turnaround into a mobster with brains to outwit all his enemies. But in between he has to make a transition from a man in control to one realizing he has been duped by all he trusted.

Director Elliott Silverstein, who got away with a lot of diversionary tactics in Cat Ballou (1965) – such as musical interludes featuring Stubby Kaye and Nat King Cole – essays a different kind of interlude here, fast cars speeding across the screen at crazy angles. But that does not work at all. Probably having realized pretty quickly that he can’t trust any of the young actors, he mostly shoots them in a group.

Some scenes are completely out of place – a multiple car crash straight out of It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, for example. But occasionally he hits the mark in ways that will resonate with today’s audience. Sureshot, confronted by a policeman, refuses to lower his hands in case he is shot for resisting arrest. Although drug use is implied rather than shown, Sureshot is so stoned he can’t remember if he has actually made love to Sandy. And like any modern Tinderite, neither knows the other’s name after spending a night together.

The strange thing about the youngsters was that they were not first-timers. Dunaway had made her debut in Hurry Sundown (1967). George Maharis had the lead in The Satan Bug (1965) and A Covenant with Death (1967), Michael Parks the male lead in The Idol (1966) and played Adam in The Bible (1966) and although it marked the debut of Robert Walker Jr. he had several years in television. Oh, and you’ll probably remember a snappy tune, the music more than the lyrics, that became a single by The Supremes.

I’ve got an old DVD copy but I don’t think this is readily available but you can catch it for free on YouTube, although it’s not a good print. Via Google you should be able to see The Supremes performing the title song.