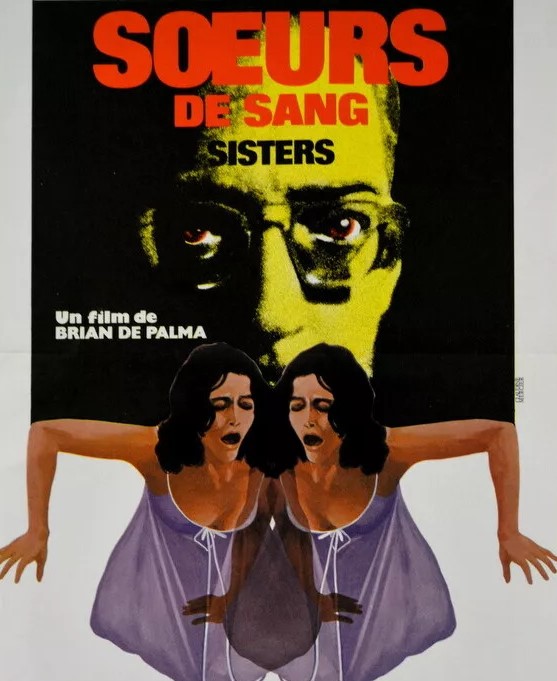

Trust Brian De Palma to invent a gameshow called “Peeping Toms.” And give Hollywood an insight into the delicious malevolence to come later in his career. Often compared to Hitchcock, this is Hitchcock diced and sliced, awash with style. Not simply inspired use of split screen but an ending Edgar Allan Poe would have been proud of. De Palma plays with and confounds audience expectation and has mastered enough of the Hitchcock approach to make the villainess more attractive than the heroine. If you’re in the mood for Hitchcock homage, this is a good place to start.

Both main characters are strictly low end, sometime model Danielle (Margot Kidder) gameshow fodder, journalist Grace (Jennifer Salt) handed run-of-the-mill reporting jobs instead of, as she would prefer, investigating police corruption. Grace also has to contend with a mother (Mary Davenport), in typical non-feminist fashion, determined to marry her off.

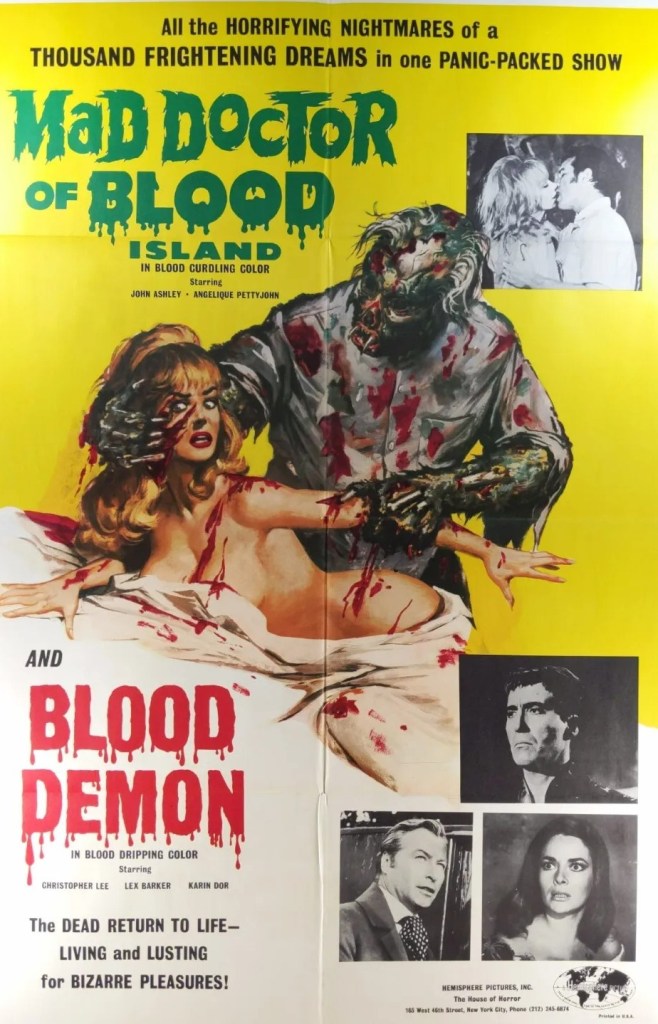

While the Siamese twin notion is straight out of the B-movie playbook and right up the street of exploitation maestros AIP, De Palma takes this idea and hits a home run. But you’ll have to be very nimble to keep up with the narrative.

Danielle meets Philip (Lisle Wilson) at the gameshow and after dinner she invites him to her apartment for sex. In the morning, he buys a surprise birthday cake for Danielle and her twin Dominique. On his return, he is murdered, an act witnessed by Grace, a neighbor across the street. She calls the police but before they can arrive Danielle’s ex-husband Emil (William Finley) – introduced to the audience, incidentally, as a creepy stalker – cleans up the mess and hides the corpse in the fold-up bed-couch.

Fans of the forensic may have trouble with this section as these days blood is more difficult to hide, but that’s evened up by the notion that a pushy journo would be allowed to sit in on the investigation. But heigh-ho, this was back in the day, so anything goes, and in any case, a la Hitchcock, it’s the woman who enters harm’s way. The cops, annoyed to hell by Grace, give up on the case and the reporter, having found the cake carrying the names of both twins, manages to destroy the evidence.

An audience searching for schlock doesn’t want art.

Grace isn’t the kind of reporter easily thwarted so she hires private eye Larch (Charles Durning) who burgles the apartment and finds proof Danielle has been separated from her Siamese twin, who died during the operation. Grace follows Emil and Danielle to a mental hospital where, in a brilliant twist, mistaken for a patient, she is sedated and becomes an inmate. Later, hypnotised by Emil, she is convinced there has been no murder.

You’re going to struggle with the sharp turn exposition takes, but, heigh-ho, how else are we going to uncover the truth. Effectively, we learn that sex releases murderous thoughts in Danielle. The detail is a good bit creepier than that, but I wouldn’t want to spoil too much.

But the ending is a corker. Grace is a prisoner. There’s another twist after that, but the notion of the investigator driven mad and ending up a prisoner of their own delusions, true Hitchcock territory, is honed to perfection here.

De Palma uses the split screen in the same way as Hitchcock employed the cutaway shot to increase the tension of potential discovery. Several sequences are rendered very effectively through this device. Oddly enough, Grace doesn’t fit the Hitchcock mold of classy heroines. She’s way too feisty and independent and there’s almost a feeling that she gets what she deserved for tramping uninvited around a vulnerable person’s life. Here, Danielle is the victim, taken advantage of by the medical profession and her creepy husband, separation from twin ravaging her intellect.

Margot Kidder (Gaily, Gaily, 1969) and Jennifer Salt (Midnight Cowboy, 1969) are both excellent in difficult roles. Charles Durning (Stiletto, 1969) makes a splash in the kind of role that made his name. As a bonus, there’s a great score from Bernard Herrmann (Psycho, 1960).

But this is De Palma’s picture, serving notice to Hollywood that here was a talent of Hitchcockian proportions.