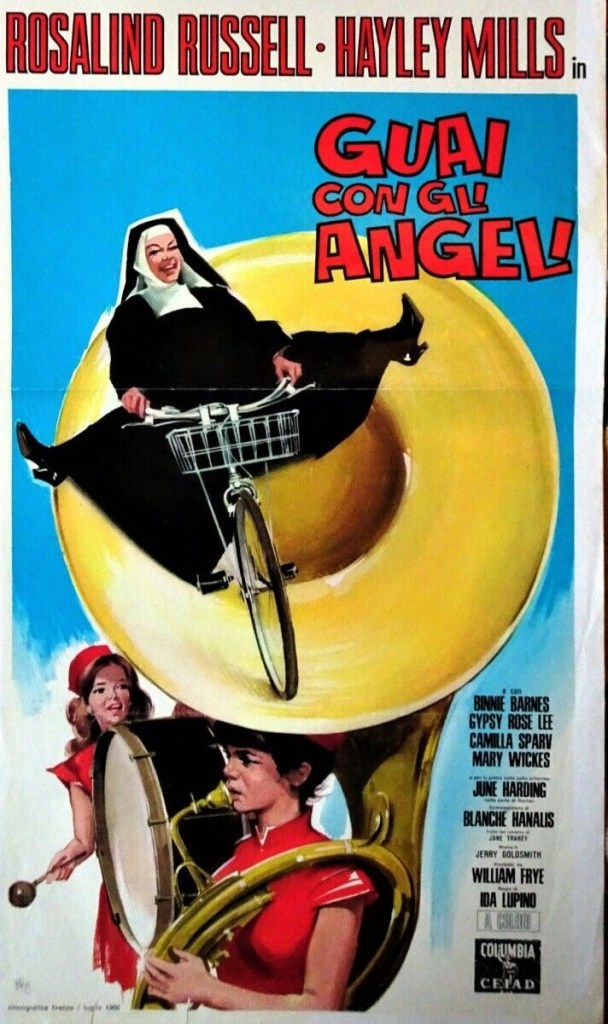

Shocking Fact No 1: director Ida Lupino was the only female director working in Hollywood at this time. And she hadn’t worked in features for over a decade. Her previous picture, The Bigamist (1953), was her fifth. And while she had continued to find work in television, the movie business shunned her. What was perhaps more shocking, as I pointed out in my book When Women Ruled Hollywood, was that in the period 1910-1919 more women worked as directors in Hollywood than at any time since and that it was a woman, Alice Guy, rather than Melies, who actually made the first narrative movie. Worst of all, despite being a major box office hit, this was Lupino’s last picture.

Shocking Fact No 2: this didn’t turn Hayley Mills into a major adult star. Oh yes, she made the transition – and how – in The Family Way later that year, a British romantic drama that saw her shed her clothes. Big hit in Britain, not so well-received in the USA. Her career then took an odd turn, into thrillers like Twisted Nerve (1968) and Endless Night (1972).

I say an odd turn because if there was any better demonstration that the actress had properly developed her comedy chops I’d yet to see it. Sure, Disney had used her in comedy, but that was mostly routine stuff. Here, she revealed an emotional maturity lacking in her previous work and, to some extent, in her future movies.

And, in part, because Lupino keeps her away from big dramatic moments, relying entirely on her facial expression to reveal character development. I am surprised that, at this point, with Doris Day’s box office allure dimming, that nobody saw Mills as her natural successor. She had the same puckish demeanor and she deftly handled comedy. Give her a few years and she would have been a natural for such polished items as Barefoot in the Park. You get the feeling there was more natural ability that was left untapped.

Anyway, on with the show.

This is just a delight. It shouldn’t work at all, certainly not for a modern audience accustomed to sharply-honed laugh lines. But it’s so cleverly constructed, in covering a three-year period, it could easily have been a string of loosely-connected episodes rather than a picture with an underlying narrative that mostly takes place beneath the surface.

Orphan Mary (Hayley Mills) has been dumped by rich playboy uncle (Kent George) in a convent boarding school that looks more like a medieval fortress than anything else. She teams up with the equally unhappy Rachel (June Harding), whose parents are at least indulgent, and together they torment the life out of the nuns and other kids, pouring detergent into tea-pots, setting off fire alarms, charging their schoolmates for an illicit guided tour of the convent, developing their smoking habits, breaking everything in sight. One scheme goes so badly awry the nuns have to take shears to a face mask.

Throughout all of this, she comes up against a tough Mother Superior (Rosalind Russell) who comes across like Miss Jean Brodie, minus her dangerously progressive side, but ever ready with a quip, able to tackle any emergency, though Mary drives her to distraction. While set in her ways, the nun does sail close to the wind, kitting out the girls in red cheerleader outfits in order to give them an unfair advantage in a marching band competition.

Any other director would have made the marching band competition the climax of the movie. I was fully expecting it to take up the final third, as pupils with little musical ability work hard and discover they can improve enough to win the competition and in so doing find out some platitudes about themselves. Instead, every episode is kept short and sweet, often the pay-off delivered in unexpected manner, for example, that we discover the girls have won when Mother Superior takes the opportunity to gloat over her rival headmaster (Jim Hutton). Or a section where teenage girls sent to buy their first bra go wild trying on all sorts of outrageous outfits that in other hands could easily have been expanded is ended sharply by Mother Superior holding up the plainest item and ordering two dozen of them.

It fairly skates along. But every now and then it dramatically slows down. And for what? Pretty much nothing at all. Just Mother Superior taking a quiet moment to herself amid all the hurly burly of running a school and dealing with mischief. But gradually, in those quiet moments, she is joined, at a distance, by a staring Mary, wondering about the nun’s inner calm.

Ida Lupino’s color palette is extraordinary. Sure, it’s nuns, so we can expect a lot of black and white. But Lupino avoids the temptation to compensate with huge swathes of color. Instead, for most of the film, the girls are decked out in grey. So when splashes of yellow or pink or red appear they are distinctive. Only as the girls grow older does more color emerge.

The wry Rosalind Russell (Gypsy, 1962) is on top form. Instead of attempting to dominate, she nips in and steals scenes with her dry delivery. She shifts from indominable to maternal and eventually engages the psychological attention of Mary in a superb scene about her own life.

In that sense Hayley Mills has her work cut out to hold her own against such an accomplished professional, which she achieves through her own delivery, but much more through facial expression. This was June Harding’s only movie. But look out for Camilla Sparv (Assignment K, 1968) in her movie debut and a cameo from Gypsy Rose Lee.

Terrific direction for Ida Lupino – watch for example how the camera closes in on characters – from screenplay by Blanche Hanalis (Where Angels Go Trouble Follows! 1968) from the bestseller by Jane Trahey.

As old-fashioned as they come and a joy to watch.

Catch it on YouTube – the first link is rent or buy, the second one is free but punctuated by adverts.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=37FnvNp2EYc