I’m conscious of puncturing a sacred arthouse cow. While applauding the cinematic bravura of Jean-Luc Godard’s debut feature that launched the French New Wave, what are we to make of a leading man who is a sexist pig? Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) refers to women repeatedly as “dogs”, complains about their driving skills, accuses them of cowardice, steals from them, forbids them to see other men, chases after them in the street to lift their dresses, constantly gropes his sometime girlfriend Patricia (Jean Seberg), and boasts of other sexual conquests.

While attempting to ape hero Humphrey Bogart, he hasn’t a shred of that star’s romantic inclination, all his energy directed towards getting sex from the nearest available female with nary a notion of love. He’s not just hard-boiled, he’s hard work, as close to the despicable males of Guide for a Married Man (1967) as you could get.

I’m no proponent of woke, but I guess audiences these days who happily accept him as thief and murderer will draw the line at his attitude to women. I found myself squirming at times at being asked to swallow this amoral character in what was otherwise a homage to the Hollywood B-picture. And it says a lot about the directorial skills that he ends up with any audience sympathy at all. And part of that certainly comes from his proximity to the more existential-minded arty Patricia. Not for the first time are we asked to re-examine our instinctive reaction to a charming thug because a sympathetic woman in either loving him or appearing to offer him understanding provides a conduit between audience and character, asking us to see him from her less judgemental perspective, no matter how misguided that might be.

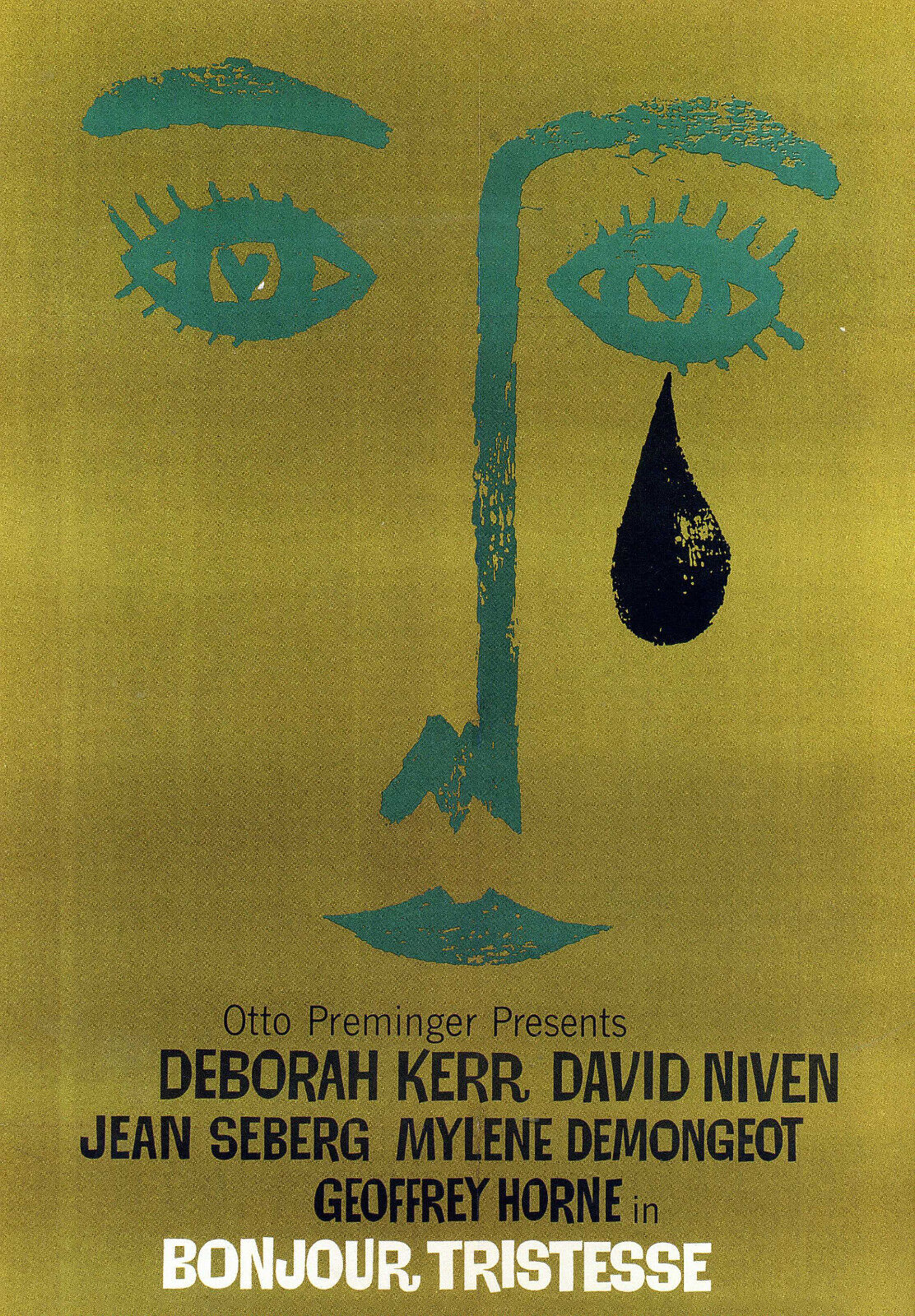

You can see the connection between the Cecile of Bonjour Tristesse (1958) and Patricia here but it’s hardly as clear-cut as Godard suggests. Patricia has qualms not just a nice comfort blanket of guilt. She’s not, as Michel wishes, some kind of sidekick or accomplice. He fails to unlock her criminal tendency as Clyde would later in the decade with Bonnie in Arthur Penn’s gangster picture. But, just as Cecile rids herself of a rival in Bonjour Tristesse, Patricia finds it relatively straightforward to turn in to the police a man for whom she has no feelings and who would prove, without the parachute of love, an irritation in her life.

Certainly, Michel is the quintessential bad guy but with entitlement issues. He wants it all, or nothing. If Santa came knocking, top of his wish list would be death. He’s a dab hand at stealing cars, can whack anybody over the head, and not above rifling through a girlfriend’s purse. But, essentially, he’s the delinquent who never grew up and Patricia is one of the many saps he’ll try to con throughout his life.

But, in fact, if you were making this today, the angle would be different. It would be the vengeful woman, as epitomized by Jenna Coleman in television mini-series Wilderness, relishing the prospect of being tagged a “bunny boiler” or predatory wolf. Much as Patricia is happy to spend some time with Michel while working out her feelings towards him, given that he is the father of her unborn child, she is far from the soft touch he imagines, betrayal in her genes.

I’m guessing budget issues contributed to much of the cinematic bravura. It’s much cheaper to eliminate close-ups, and to film outdoors where light is less of an issue than indoors, and where nobody’s bothering to seek civic approval to shoot. So, there’s certainly a freshness, a boldness, the kick in the pants that stuffy Hollywood with its insistence on certain procedures required.

The camera is restless, not just in the tracking shots (especially the famous final one), but in bobbing around, as if questioning just what was the Hollywood obsession with nailing everything down, keeping it fixed, as if the camera was merely a tool rather than a means of directorial expression. And Godard does bring to exceptional life characters who would otherwise be passersby, dreamers who are more likely to fail than succeed, who try to provide themselves with codes as if that will assuage inner doubt.

Except for her self-preservation instincts and urge for independence, there’s every chance that Patricia would end up the dissatisfied housewife, especially with baby in tow. Michel is a dumb criminal, not the heist genius of so many other movies. Cocking a snook at authority might be the only true freedom he ever attains.

I’m not sure this was part of Godard’s thinking, but it’s plain to me that Michel’s biggest problem is crossing over into the real world. The minute he comes up against a woman who lives an ordinary life, albeit with elevated expectation, he comes a cropper because she doesn’t subscribe to his limited world-view. It’s not exactly a clash of cultures, because, in reality, she’s every bit as vicious as him. If she loved him, it might be a different story. But as with Jenna Coleman in Wilderness, fail to safeguard that love and it’s curtains.

Without doubt a singular earthquake of cinematic proportions, freeing up a generation to filmmakers to challenge the hierarchy, but requiring reassessment in view of its dubious attitude to women.