The property had been bouncing around Hollywood for over decade. It had its origins in the true-life tale of the five Marlow brothers involving murder, revenge, and jailbreak, the story making national headlines when the case was heard at the U.S. Supreme Court in 1892. Based on the book The Fighting Marlows by Glenn Shirley,William H. Wright (Assignment in Brittany, 1943) shopped around a screenplay, jointly written with Talbot Jennings (Northwest Passage, 1940), that was purchased by Paramount in 1955.

Alan Ladd (Shane, 1953), who owed the studio a movie, was cast in the lead and the script went through rewrites by Frank Burt (The Man from Laramie, 1955) and Noel Langley (Knights of the Round Table, 1953) with shooting scheduled for 1956. John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven, 1960) was set to direct until Ladd quit, having bought his way out of his contract. Burt Lancaster (The Train, 1966) was brought in as his replacement.

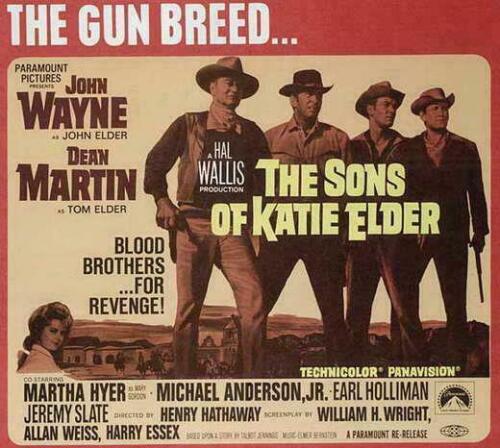

When Lancaster dropped out, producer Hal Wallis took over the movie in 1959 and considered replacing him with James Stewart (Shenandoah, 1965) or Charlton Heston (The Hawaiians, 1970) with Dean Martin (Rio Bravo, 1959) as the second lead. But still the movie stalled for another five years before Wallis settled on John Wayne who signed on for $600,000 plus a one-third share of the profits and one-third ownership of the negative (a bounty that would continue to pay off through reissues and leasing to television). Henry Hathaway was paid a flat $200,000.

Wayne and Hathaway had history dating back to The Shepherd of the Hills (1941) based on the million-copy bestseller by Harold Bell Wright, and groundbreaking in its use of Technicolor, then in its infancy. They didn’t work again until desert treasure hunt Legend of the Lost (1957) which teamed Wayne with Sophia Loren. A few years later came North to Alaska (1960) followed by Circus World / The Magnificent Showman (1964).

Despite this long-term relationship, the most the director could offer about his star was that “Wayne is more particular about the pants he wears than anything in the world…unless he gets the thinnest kind of material it drives him crazy.”

When the script was finally knocked into shape, the Marlow siblings had been trimmed from five to four, and that family had been replaced by the Elders, a nod to western aficionados who would recognize the name Katie Elder (“Big Nose Kate”), occasional companion of Doc Holliday whose story Wallis had previously filmed as Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957). Even though Elder wasn’t dead enough – she lived till 1940 – to conform to this picture, it seemed an odd decision to choose that name unless resonance was expected.

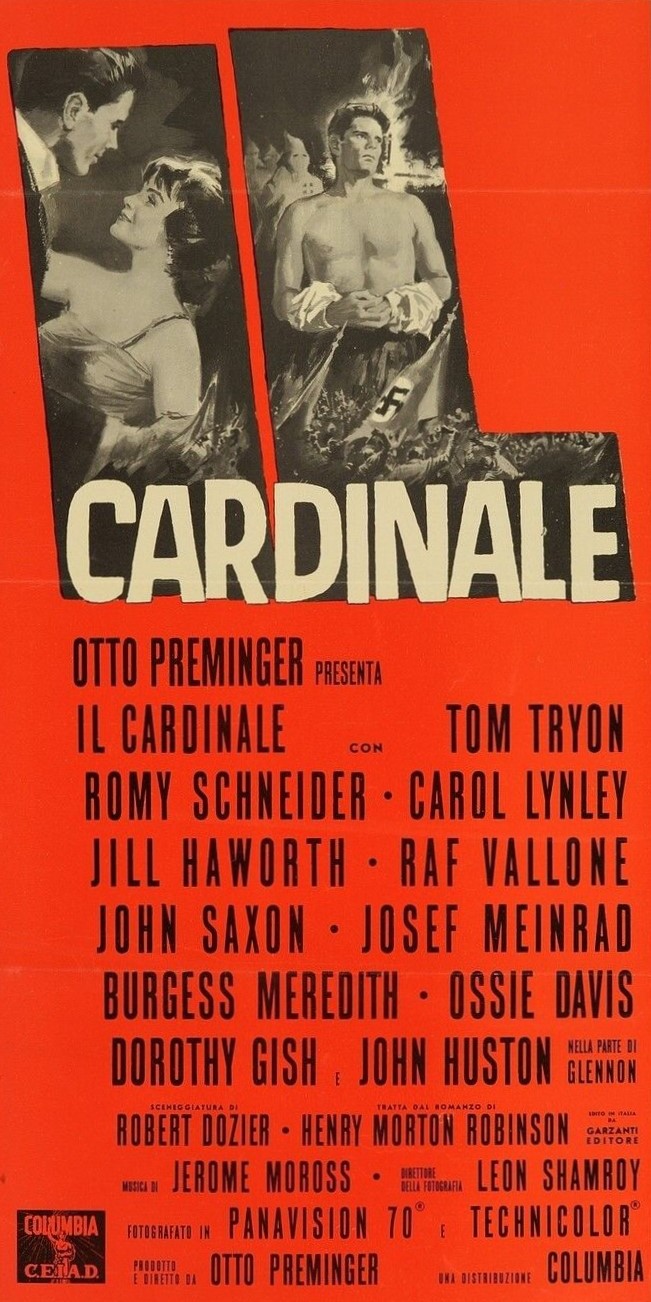

But it was still far from a done deal because Wayne’s cancer threatened to scupper the picture. Start of shooting scheduled for October 20, 1964, was shuttered when the disease was diagnosed on September 13 following the completion of Otto Preminger WW2 epic In Harm’s Way (1965). Aware surgery might jeopardize the picture, Wayne suggested Wallis replace him with Kirk Douglas (Cast a Giant Shadow, 1966).

Hathaway rejected the notion, but while neither star nor producer had any idea whether the operation would be successful, and whether Wayne would be even fit enough to work, or – God forbid, that the actor might already have made his last picture – Wallis took an optimistic approach and announced the picture would be delayed for a month and “even a little later.” Hathaway’s optimism was based on the fact that he had survived colon cancer a decade before.

At least the surgeon moved fast, operating four days after diagnosis, and again five days later. As well as fighting the damage surgery and pain had done to his body, Wayne found himself slipping into depression, convinced the operation would render him unemployable. “I’ll never work again if they find out how sick I am. If they think an actor is sick, they won’t hire him,” he said, a legitimate observation given the cost of shutting down a picture should the actor be unable to play his role.

Wallis’s business partner Joseph Hazen shared Wayne’s pessimism and urged the producer to recast with either William Holder (The 7th Dawn, 1964) or Robert Mitchum (The Way West, 1967). Paramount, too, fretted about insurance, the studio couldn’t risk hiring an uninsurable actor. Wallis refused to abandon Wayne and the studio finally agreed to tough conditions from the insurance company. So, on January 6, 1965, the principals gathered in Durango to commence the 46-day shoot on a production budgeted at $3.19 million.

The high elevations – 8,500 ft in places – were not conducive to someone recovering from a lung cancer operation and Wayne found it difficult to breathe. It didn’t help that on the fourth day of shooting Wayne was expected to jump into icy water for the sequence where the brothers were ambushed by the villains. It didn’t help, either, that Wayne was too big to wear a rubber suit to stave off the cold like his fellow actors.

Wayne never complained that Hathaway “worked me like a damn dog.” He realized that it “was the best thing ever happened to me. It meant I got no chance to walk around looking for sympathy.” The star put on a brave front, publicly acknowledging his battle with cancer as a way of giving hope to others while privately terrified not so much of dying but of being helpless. “I just couldn’t see myself lying in bed…no damn good to anybody.”

“He had to be the macho man,” commented Earl Holliman (The Power, 1968), a late substitute for original star Tommy Kirk (Swiss Family Robinson, 1960) who was sacked after being caught smoking marijuana, “he had to have more drinks than the next guy.” And despite the severity of his condition, and although publicly pretending he had given up tobacco, he continued smoking cigars.

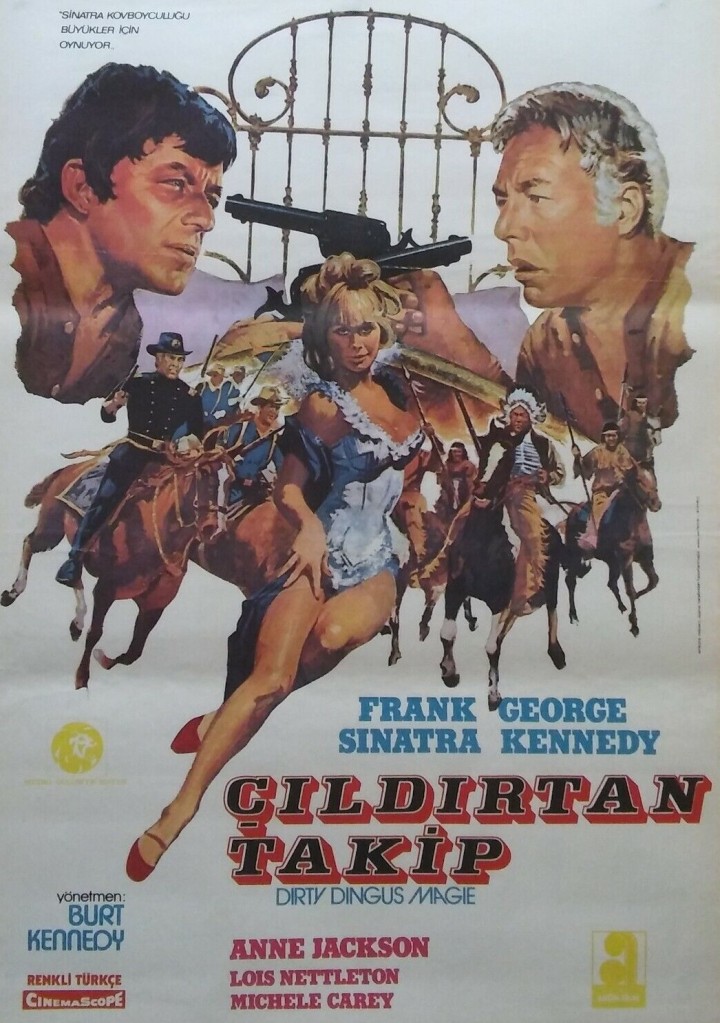

Recalled Dean Martin (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967), “He’s two loud-speaking guys in one.” George Kennedy (Cool Hand Luke, 1967) asserted, “If you put him in a group with other movie stars, the eye went to him and that is the ultimate marker of respect. He was John Wayne. He was very real. It didn’t matter if he wasn’t Olivier; Olivier wasn’t John Wayne.”

But there were outward signs of the effect the illness had upon him. He was less sure of himself on a horse, riding with a shorter rein out of fear a horse would get away from under him, trying to minimize the chances of falling or being bucked from the animal. And as the film wore on, an oxygen inhaler was set up beside him on set.

Dennis Hopper (Easy Rider, 1969) was wary of working again with Hathaway after a difficult experience with him on From Hell to Texas (1958) starring Don Murray and Diane Varsi where the actor suffered the indignity of endless takes. Hopper quit three times and for good measure the director put the word around and virtually grounded the actor’s career. Hopper only made one movie in six years. In the interim he had married Brooke Hayward, daughter of actress Margaret Sullavan whom Hathaway respected, and peace was brokered.

Although on his best behavior on the shoot, Hopper was no less impressed. “He was a primitive director, he rarely moved his camera, the movement came from the actors.”

“Westerns are art,” declared Wayne. “They’ve got simplicity and simplicity is art…There’s simplicity of conflict you can’t beat…Westerns are our folklore and folklore is international…In Europe they understand that better than we do over here. “

Whether it was public sympathy for an ailing star and his resolve to fight cancer, or audience delight that he was back in a western after a gap of a few years, The Sons of Katie Elder was a huge hit with $5 million in initial rentals (what studios were left with after cinemas had taken their share). It earned more later in reissues but that initial sum was enough for thirteenth spot in the annual box office rankings though beaten by both Shenandoah and Cat Ballou. Its foreign earning would probably match domestic, to make it one of Wayne’s biggest earners for the decade.

SOURCES: Scott Eyman, John Wayne: His Life and Legend (Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2014) p111, p387-396 ; Ronald L. Davis, Duke: The Life and Image of John Wayne (University of Oklahoma Press, 1998) p266; Hal Wallis Collection, Margaret Herrick Library; Hedda Hopper, “Ladd To Star in Film of Pioneers’ Reunion,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 9, 1955, p16; Thomas M. Pryor, “Hecht-Lancaster Obtains 2 Novels,” New York Times, January 12, 1956, p22; Oscar Godbout, “TV Movies Extras Get Salary Rises,” New York Times, July 3, 1956, p17; John Wayne, “Me? I Feel Fine,” Los Angeles Times, January 18, 1965; James Bacon, “Wayne’s Biggest Bout vs. Killer Cancer,” Los Angeles Herald Examiner, March 14, 1965; Roderick Mann, “John Wayne – A Natural as The Shootist, Los Angeles Times, March 7, 1976.