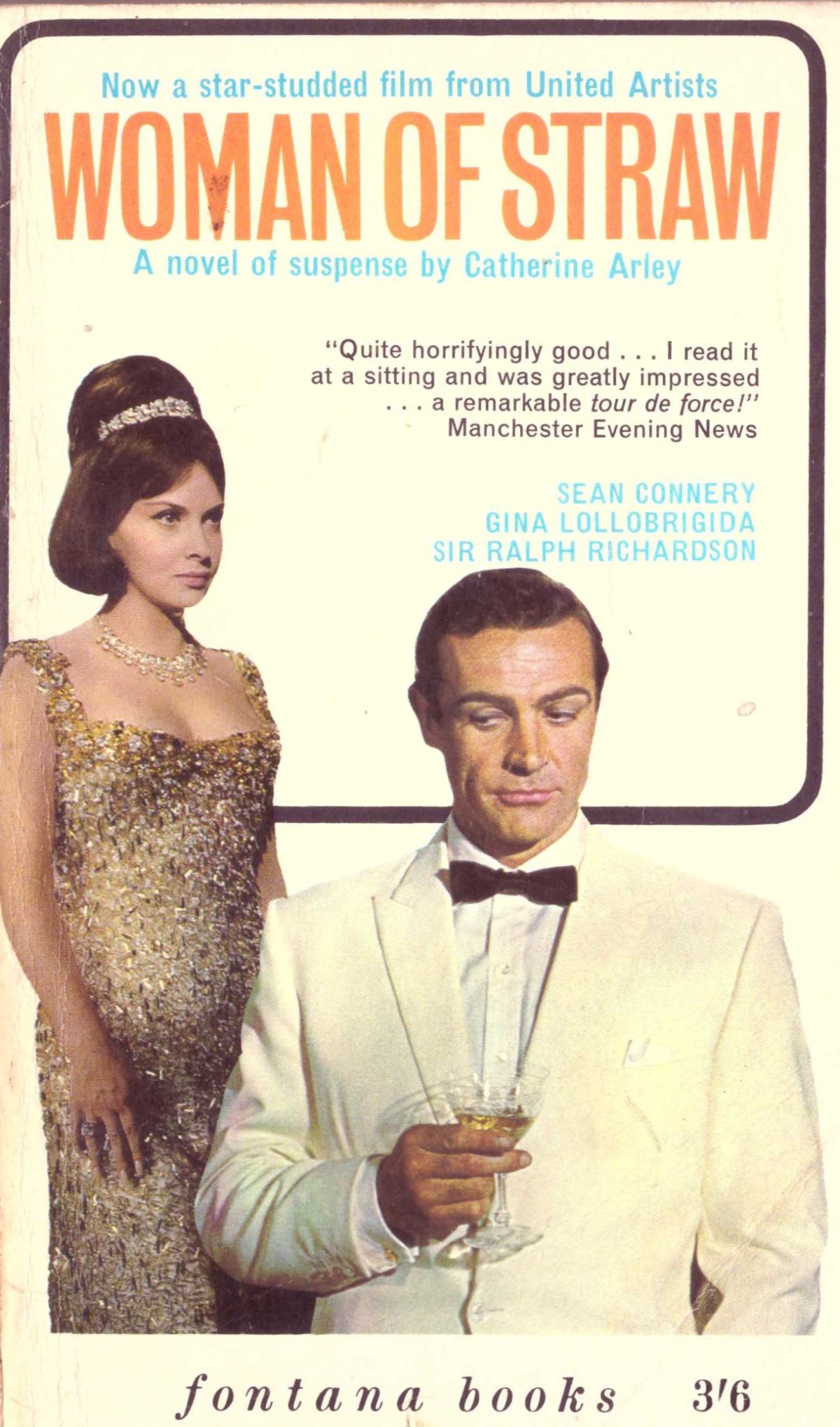

A new episode in the James Bond legend began on February 23, 1966, when a plasterer from Scotland made an audacious bid for movie stardom. His name was Neil Connery, currently earning $10 a week, shooting for a $5,000 payday as he took part in a screen test in Rome for producer Dario Sabatello (Seven Guns for the MacGregors, 1966) for a film entitled Operation Casbah that would later be tagged Operation Kid Brother (O.K. Connery in Italy).

Sabatello was an experienced producer beginning with The Thief of Venice (1950) starring Hollywood legend Maria Montez. Connery was a skilled laborer living in the four-year shadow of elder brother Sean and with little intention of moving out of that shadow. However, as a result of a work-related incident, he became the subject of a newspaper article and then a radio interview. Nobody was much interested in the reason for the interview – stolen tools – but everyone was impressed by the sound of Neil’s voice. “Sean’s brother spoke exactly like him.”

The newspaper interview caught the eye of Sabatello, who noted the actor’s likeness to his brother and who flew over to Edinburgh to interview Neil and in so doing becoming aware of his athletic attributes, height and good looks. A month later came an invite for the screen test. Neil’s agent, who had no right to make such a claim, promised that if Neil got the part big brother Sean would play a cameo. For the test, Connery had to “embrace a girl, sing, dance and finally end up in a hand-to-hand fight with a guy with a knife.” However, the test was so successful that the presence of Sean was not required. Sabatello signed the neophyte actor to a six-picture deal that would generate a six-figure salary if the film turned the Scot into a star.

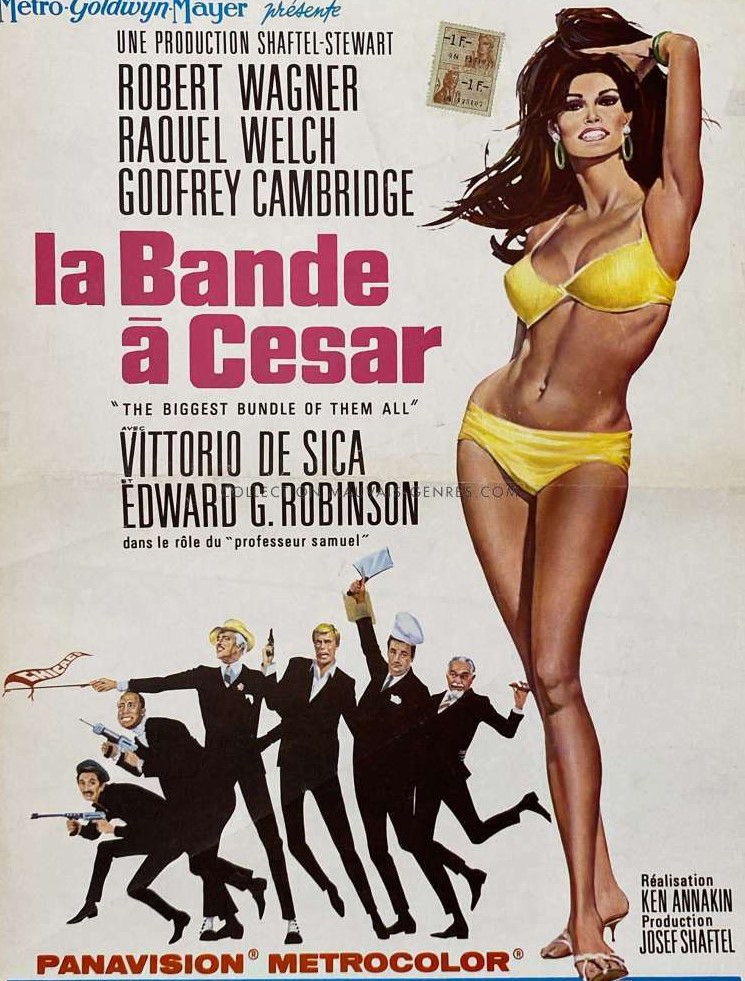

Italian production giant Titanus sold the world rights (except for Italy) to United Artists, ironically the distributor of the James Bond pictures, thus securing the funding for the $1.2 million three-month shoot that kicked off in Cinecitta in Rome on December 14, 1966. Locations were scheduled to include Monte Carlo, San Remo, Turin, Barcelona, Malaga and Tetuan.

The supporting cast was dominated by actors with a Bond connection including Adolfo Celi, Daniela Bianchi, Anthony Dawson, who had all worked with director Alberto De Martino on Dirty Heroes (1967) and Lois Maxwell and Bernard Lee. Ennio Morricone, another De Martino aficionado, was brought in to do the score.

Connery’s boxing training in the British Army came in handy when he had to become an archer. Pulling a bow takes considerable physical exertion. Target practice was held at Adolfo Celi’s house outside Rome. “I had remembered everything about putting the bow down, bringing it up, pull and push, as there was quite a pull on it,” he said. Celi’s arrow managed just a few yards but Connery hit the target. His luck did not hold when filming the real thing in Monte Carlo. Celi’s shot did not go far again but this time Connery’s arrow missed the target.

Although Connery had read the script he was only given his lines in the morning as he went into make-up. He acquitted himself well in the fight scenes, except for one scene which ended with him being taken to hospital.

The film opened in Britain at the Pavilion in London’s West End on April 25, 1667, with a general release slated for May 5. But it didn’t get a circuit release. That is, it didn’t go out on either of the two main cinema chains, ABC or Odeon, or the lesser Gaumont circuit, so its bookings would have been restricted. It didn’t appear in the United States until November, 1967, having been reviewed without much enthusiasm in Variety which posited “at best the film deserves bottom half bookings”, i.e. the bottom half of a double bill, which means it would play for a fixed rental rather than a percentage.

It did open in first run in a number of city center picture houses in November and December, to occasionally decent but hardly lush box office. Its $20,000 week in Chicago was deemed “good”, as was the $4,000 in Providence, while $13,000 in Philadelphia was considered “brisk” but $5,000 in St Louis considered only “fair.” There was a first run showing in New York but only at a 600-seater arthouse.

But when it went wider in “Showcase” releases the box office collapsed. In New York it managed only $67,000 from 25 theatres compared to, in the same week, British film The Family Way on $223,000 from 26, and the second week of Point Blank with $145,000 from 25. Business was worse in Los Angeles, just $49,000 from 26 compared to $125,000 from 29 for Barefoot in the Park, and it was dire in Kansas City, only $9,000 from eight houses.

Given the relatively low budget, the film globally may well have broken even but it certainly did not send Neil Connery’s box office status into the stratosphere. He had small parts in two more low-budget movies, The Body Stealers (1969) and Mad Mission 3: Our Man from Bond St (1984) plus some television.

SOURCES: Brian Smith, “Bond of Brothers,” Cinema Retro, Vol 4 Issue 12 2008, p13-19; Allen Eyles, Odeon Cinemas 2, (CTA 2005), p212; Allen Eyles, ABC (CTA, 1993), 123-124; Allen Eyles, The Granada Theatres (CTA 1998)’ p247; Allen Eyles, Gaumont British Cinemas, (CTA 2005), p197; William Hall, “Big Brother Is Watching Him,” Photoplay, June 1967; “International Soundtrack,” Variety, February 23, 1966, p33; “Titanus Sets Pre-Prod Deals for Two UA Pix,” Variety, December 14, 1966, p24; “International Soundtrack,” Variety, December 21, 1966, p24; “Hollywood and British Production Pulse,” Variety, December 28, 1966, p17; Advertisement, Variety, January 4, 1967, p65; “Connery Pix a Family Affair with UA,” Variety, March 8, 1967, p24; Review, Variety, October 11, 1967, p22; “Picture Grosses,” Variety November 1, November 8, November 15, November 29, December 13, 1967.