In 1964, Twentieth Century Fox created a new way of selling pictures by inventing the advance buzz.

Of course, movies had always had some kind of pre-launch push but mostly on a small-scale via gossip columnists, who, while they had some influence, did not actually receive much space in a newspaper. Fox set out to change all that and put movies on the front pages and gain big feature spreads inside, an event that only usually occurred through unwanted scandal (Cleopatra, for example), death or a photo of a big female star.

Fox revamped the press junket – at that time primarily used as a vehicle to announce a movie premiere – and turned it into a method of creating advance publicity and expanding awareness on new pictures long before they reached the screen. And did so with enormous style, transporting over 100 American journalists to Europe to watch the production of three major big-budget roadshows.

Cecil B. DeMille of all people had invented the movie press junket – for the world premiere of his swashbuckler The Buccaneer in 1938. At a time when world premieres were confined to New York and Los Angeles, Hollywood had begun experimenting on a small scale with different locales for a first showing – whaling picture I Conquer the Sea (1936) was unveiled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, The Petrified Forest (1936) in St Louis and Sutter’s Gold (1936) in Sacramento. But these were all local affairs, the selected city putting on a big show for local dignitaries but the media were drawn only from the immediate surrounding area with stories syndicated to bigger newspapers.

When he selected New Orleans for his world premiere, DeMille, as skilled in marketing as he was in direction, hired a deluxe train to bring journalists from the top newspapers and magazines down from New York and Chicago. The train had a special compartment kitted out with typewriters, telephones, radio, Dictaphones and even stenographers to “relay hot news as it happens.”

All expenses – accommodation, meals, alcohol and various other sundries – for an entire week were picked up by Paramount. Three radio stations made daily broadcasts and the journalists filed news stories and features about the stars and the city, and, most important of all, reviews of the film they were privileged to be the first to see. The city went to extraordinary trouble, proclaiming a local holiday, organizing parades, enlisting the help of local organizations to ensure there was some event worth reporting every day. Local retailers, hoteliers and restaurateurs made a fortune as hundreds of thousands of people piled in to see the stars and witness the festivities.

The press junket was born.

In the following years, world premieres were held all over America either in locations where the movie was filmed or places linked with a star or character. These varied from major metropolises like Detroit (Disputed Passage, 1939), Houston (Man of Conquest, 1939), Memphis (Dr Erlich’s Magic Bullet, 1940) and Philadelphia (Intermezzo, 1939) to smaller locales like Littleton, New Hampshire (The Great Lie, 1941) and South Bend, Indiana (Knute Rockne, All American, 1940).

But by the 1960s, the world premiere idea had been done to death. There was scarcely a town, city or venue that had not been the subject of premiere marketing.

So in 1964 with an unprecedented three roadshow pictures in production Twentieth Century Fox upped the press junket ante by flying a fleet of 110 journalists on a specially chartered Boeing 707 to Europe to watch filming on actual locations in Britain, Austria and Italy.

Over 40 cities were represented by reporters and included representatives of the New York Post, Los Angeles Times, UPI, Detroit Free Press, Kansas City Star, Boston Globe and the Seattle Times as well as The Mike Wallace Show (television) and NBC Radio and magazines as diverse as McCalls, Cue and Newsweek.

At the reconstructed Booker Airport in Britain, journalists watched stunts for Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines (1965) and interviewed stars like Sarah Miles, Terry-Thomas and Robert Morley. Each journalist had a photograph taken as a personal souvenir alongside a replica of a 1910 Antoinette airplane specially built for the film, but undoubtedly many such photographs found their way into the newspapers and magazines.

When the media cavalcade shifted to Austria they were treated to a massive banquet at Schloss Klessheim in Salzburg where The Sound of Music (1965) was being filmed. Julie Andrews was interviewed with her feet on a table and the reporters watched choreographer Marc Breaux rehearsing the “I Have Confidence” number (the music had been recorded in Hollywood and then played back synchronized to the action). Andrews and co-star Christopher Plummer were interviewed at Frohnburg Castle.

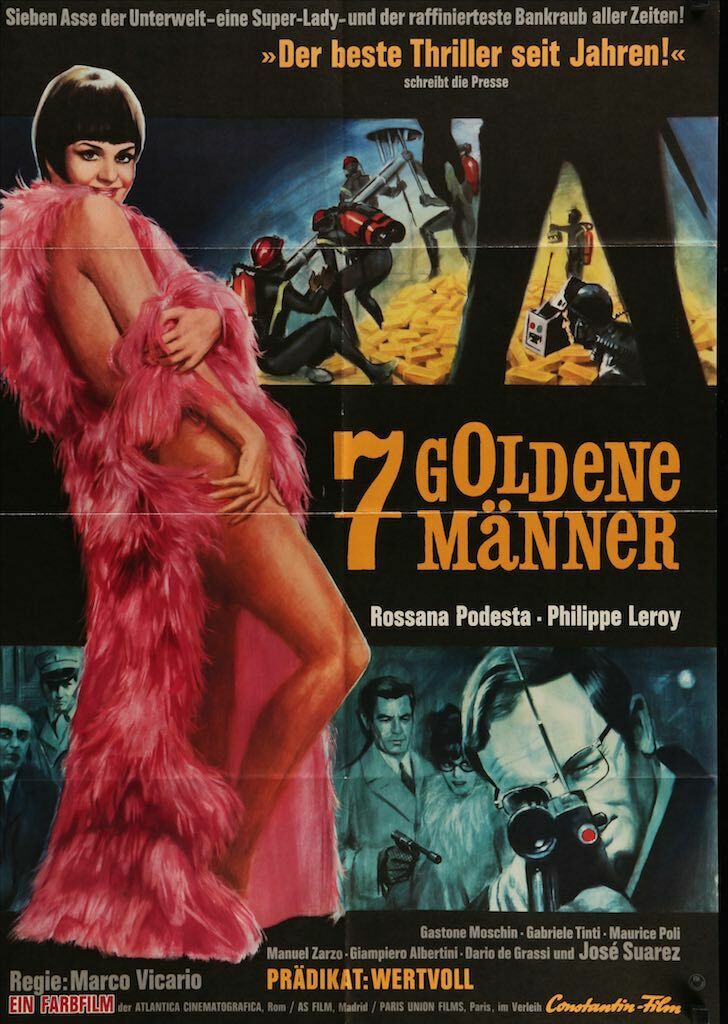

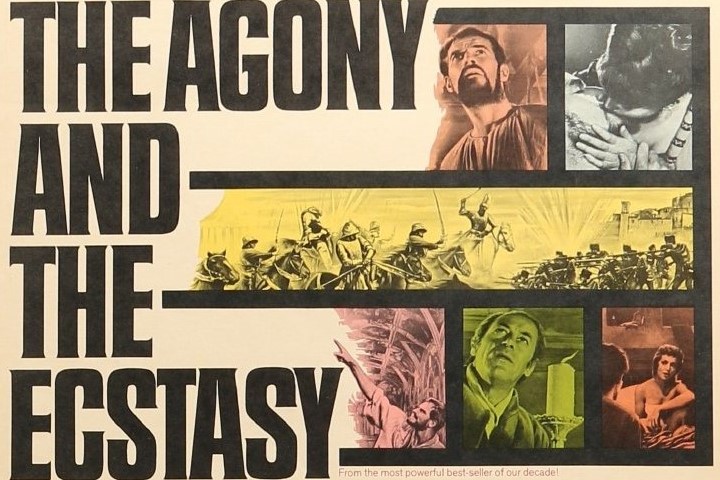

Italy – where The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) was being shot – was the final destination. The visitors were conveyed up the perilous Carrera Mountains to the 4,700 ft Monte Altimissino to watch a scene being filmed in a quarry usually closed to visitors of a 200-ton block of marble being cut. Director Carol Reed, producer Darryl F. Zanuck and star Charlton Heston were on hand to welcome them. Rex Harrison (playing the Pope) was interviewed outside a restaurant in Rome that bore the Pontiff’s name

Even before the journalists returned from the seven-day trip, they were sending stories back – over $8,000 (worth about $70,000 today) was spent on cable fees and nearly one million words had been written. Many of the journalists had never been to Europe before and took full advantage of the opportunity. Newspaper and magazines would not permit journalists to spend such a length of time away from the office without expecting a substantial bounty in the shape of news stories – the trip itself received extensive coverage.

Feature editors were deluged with stories and interviews that ran in the main sections of the newspaper and in weekend supplements, shifting the coverage of movies away from the entertainment sections. In addition, to justify their time away, stories ran in the food, travel and fashion sections.

It was an unprecedented publicity bonanza for films that were still a full year away from release, creating a tsunami of public interest. For the first time a studio had created movie awareness on its own terms. While movies filmed in Europe had often received coverage based on reports by journalists living in that continent, this was rather cursory, had always appeared piecemeal in American newspapers, largely depended on an editor’s decision about reader interest in a particular star, and, more importantly, such stories usually coincided with the film’s launch rather than well in advance.

This huge media onslaught whetted public appetites well in advance. In addition, there were enough articles left over to be used up when the movies actually did open.

The trade press also widely reported on the event and Box Office magazine ran a 12-page feature one month later. In its evaluation of the junket, the studio concluded that it was the “most advanced type of industrial marketing.”

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, In Theaters Everywhere: A History of the Hollywood Wide Release 1913-2017, p32-36 (McFarland Publishing, 2019); “That Was the Week That Was…Fantastic,” Box Office, Jul 6, 1964, p10-21.