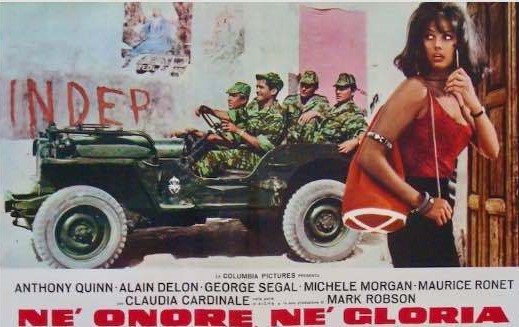

Remembering this picture as a summer holiday matinee of stiff-upper-lip-ness entangled in all sorts of Khartoumery, I came at this film with low expectations. Given producer Charles H. Schneer’s (First Men on the Moon, 1964) involvement, there were no Ray Harryhausen magical special effects. I was only aware of star Anthony Quayle as a bluff supporting actor in epics like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) and Sylvia Syms as a willowy supporting actress (The World of Suzie Wong, 1960). So I was in for a pleasant surprise. Take away the back projection, stock footage and the unlikely zoo of wild animals and there is a fairly decent action film set in the Sudan on the fringes of the Mahdi uprising (that story filmed as Khartoum the following year).

Quayle is a former army sergeant awaiting court martial when he escapes from a battle near Khartoum, ends up saving governess Syms, her charge Jenny Agutter (making her debut), officer Derek Fowlds (BBC Yes, Minister) and a wounded soldier. The motley crew flees down the Nile in a boat. You know you are in for something quite different when the soldier dies and Quayle wants to toss him overboard. Overruled by prim Syms and stiff upper lip Fowlds, this good deed is rewarded by losing their beached boat while burying the dead. A picture like this only survives on twists. Burning the remainder of their boat to attract the attention of the British relief force only brings in their wake a mob of Arabs, who we are informed, in a spicy exchange, don’t know the ten commandments, especially “thou shalt not kill.” It turns into a battle of the sexes, with Syms’ innocence and good breeding quickly eroded in the face of danger, her natural antipathy towards a scallywag like Quayle softening. Lacking due deference, said scallywag is given some choice lines which spark up proceedings. It being Africa, the animals have nothing better to do than torment them, so cue snakes, crocodiles, charging rhinos, hippos, elephants without even an entertaining monkey to lighten proceedings. Quayle sets his ruthless tendencies to one side to take a tender, paternal interest in young Agutter. Ongoing action prevents the usual male-female meet-cute African Queen-style banter and it’s all the better for it.

Capture by African tribesman takes the story on an interesting detour. Quayle, attempting to make friends, shouts out despairingly (and without irony), “Don’t any of you even speak English?” only for chieftain Johnny Sekka (The Southern Star, 1969) to stride out of the bushes with the reply, “I speak, English, Arabic and Swahili.” Quayle explains, “We come in peace.” Sekka retorts, “With gun in hand?” Game on! The plot goes offbeat when we become involved in Sekka’s life. A former slave, his village presents an unusually realistic alternative world not least for Agutter, ill by this time, saved by an African witch doctor. There are further surprises, clever ruses to foil the enemy, revelations about Syms and a surprising but very British ending.

Quayle is convincing, reveling in the opportunity to create a fully-formed character rather than confined to a small chunk of a picture. Syms, too, with more on offer than normal, Agutter (Walkabout, 1971) not a precocious Disney cut-out, and Fowlds revealing what did for all those years before turning up on television as puppet Basil Brush’s sidekick. As a British B-picture making do on a small budget, it overcomes this particular deficiency with some sparkling dialogue and attitudes that go against both the time in which it was set and the era in which it was made.

NOTE: Khartoum, The Southern Star, The Fall of the Roman Empire, The Southern Star and First Men in the Moon (with Harryhausen effects) have all been reviewed on this blog.