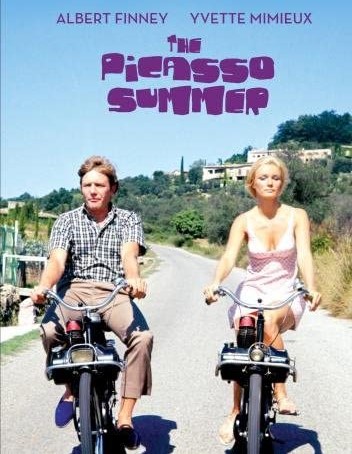

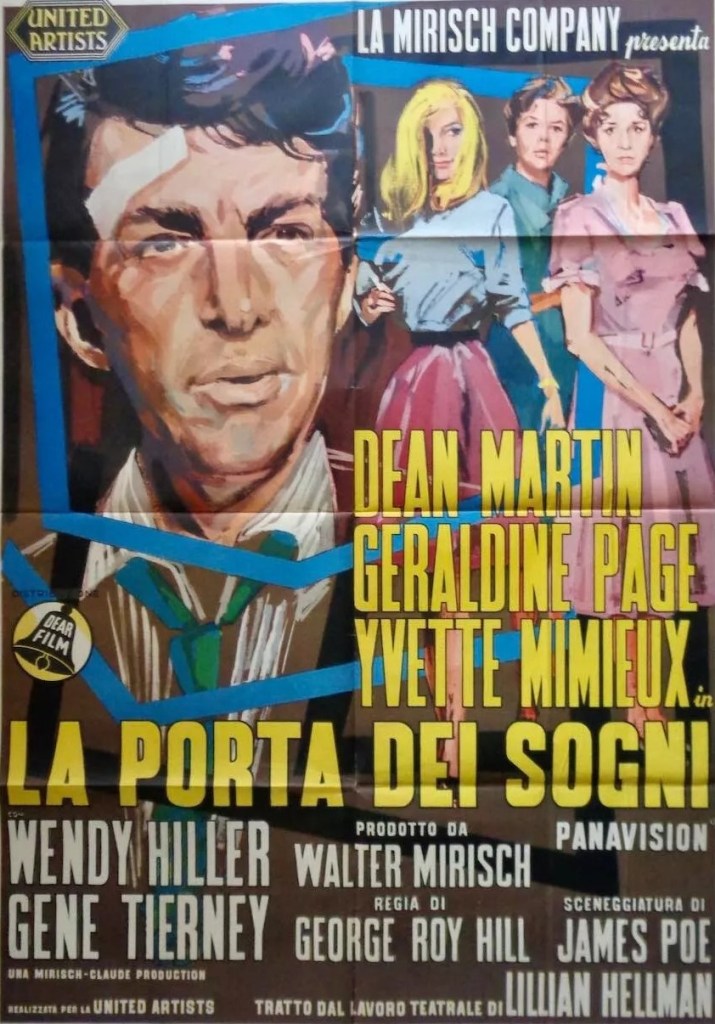

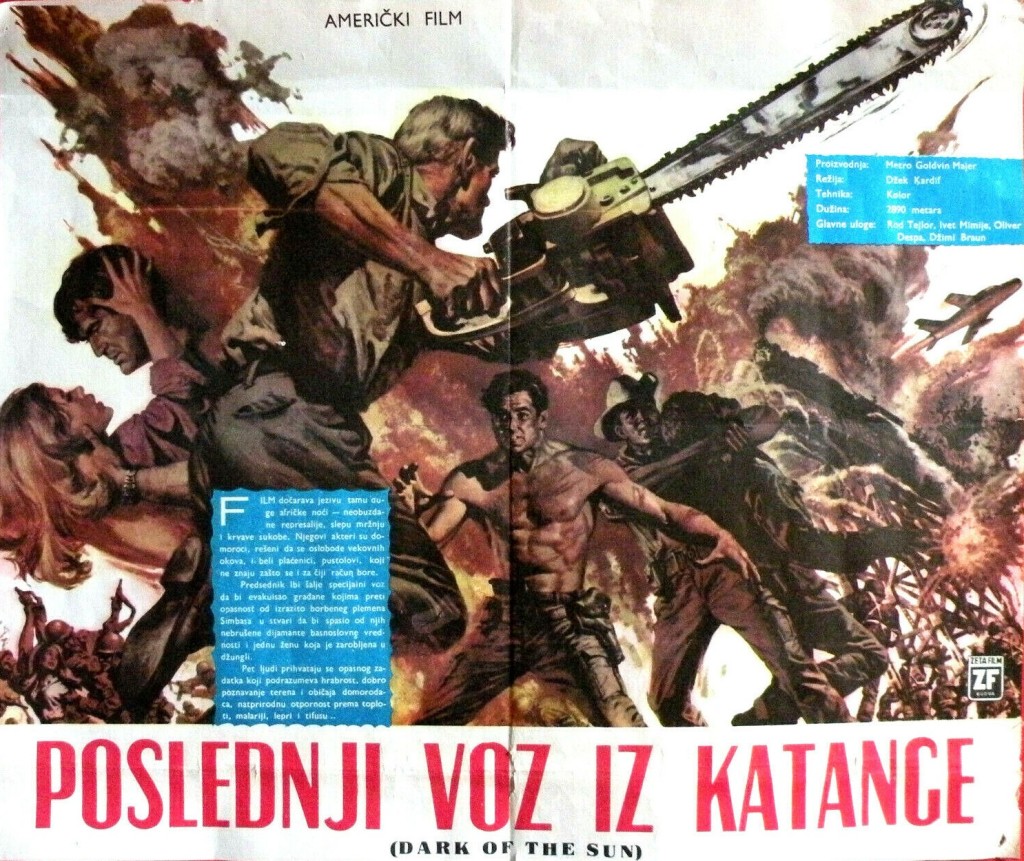

Must-see for collectors of cinematic curios. A treatise on entitlement, bullfighting, Picasso, the impact of celebrity on everyday lives and the hermaphroditic qualities of snails? Or an innovative piece of moviemaking through its use of a jigsaw split-screen, an audacious reimagining of the painter’s work, documentary and animation. Or despite the involvement of top talent like Albert Finney (Tom Jones, 1963), Yvette Mimieux (Dark of the Sun, 1968), composer Michel Legrand (The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968) and writer Ray Bradbury (Fahrenheit 451, 1966), rightly consigned to the vault and never given a cinema release.

George (Albert Finney), a disenchanted San Francisco architect who designs warehouses, and wife Alice (Yvette Mimieux) take a holiday in France to rekindle his love of Picasso and set out to find and – in in a severe case of early onset entitlement – talk to the legendary painter. So they fly to Paris, take the train to Cannes and cycle around. Romance, it has to be said, in that idyllic countryside is the last thing on his mind, although George does pluck a guitar and sing a love song on a riverbank and they do dally in the sea. And he is far from a stuffed shirt, in one scene stealing a boy’s balloon to prevent the kid hogging a telescope.

There are barely ten lines of meaningful dialog, though Alice’s frustration at her husband’s obsession is soon obvious. The best sequences are the reimagining of Picasso paintings as animation. Picasso broke down the world, so we are told, and represented it as his own so by this token it seems pretty fair to do the same to the artist’s work. In the best scene George turns toreador (not sure the budget ran to stuntmen) facing up to a real bull. But there is plenty Picasso to make up, including a candlelit walk along the “Dream Tunnel” displaying the artist’s War and Peace murals, a lecture on the painter’s ceramics and his self-identification with death in the bull ring.

And there is a twist at the end, as the couple on a beach do not loiter long enough to see a man resembling the famed artist make Picasso-like drawings on the sand. But mostly it’s a story about American entitlement, that a painter should not shut himself off from the world in order to prevent the world stopping him getting on with painting. When George, denied entrance or even acknowledgement of his bell-ringing, stands at the gate to the Picasso villa, it is almost as he is the one imprisoned by his need for celebrity. Half a century on, the need for ordinary lives to be validated by contact with celebrities has become an insane part of life. The fact that the impossible mission ends in defeat (“everything is still the same”) lends a tone of irony.

Finney’s box office status at this point in his career allowed him to retain his thick Lancashire accent – Sean Connery managed that trick for his entire career. As in Two for the Road (1967) he does a trademark Bogart impression and eats with his mouth open. And he is game enough to stand in a bull ring with a raging bull. Yvette Mimieux is scandalously underused, insights into her thoughts conveyed by lonely walks through night-time streets, although she is the only one to fully appreciate art when she comes across a blind painter (Peter Madden). The best part goes to Luis Miguel Dominguin playing himself, a bullfighter and renowned friend of Picasso. In the incongruity stakes little can match Graham Stark (The Plank, 1967) as a French postman.

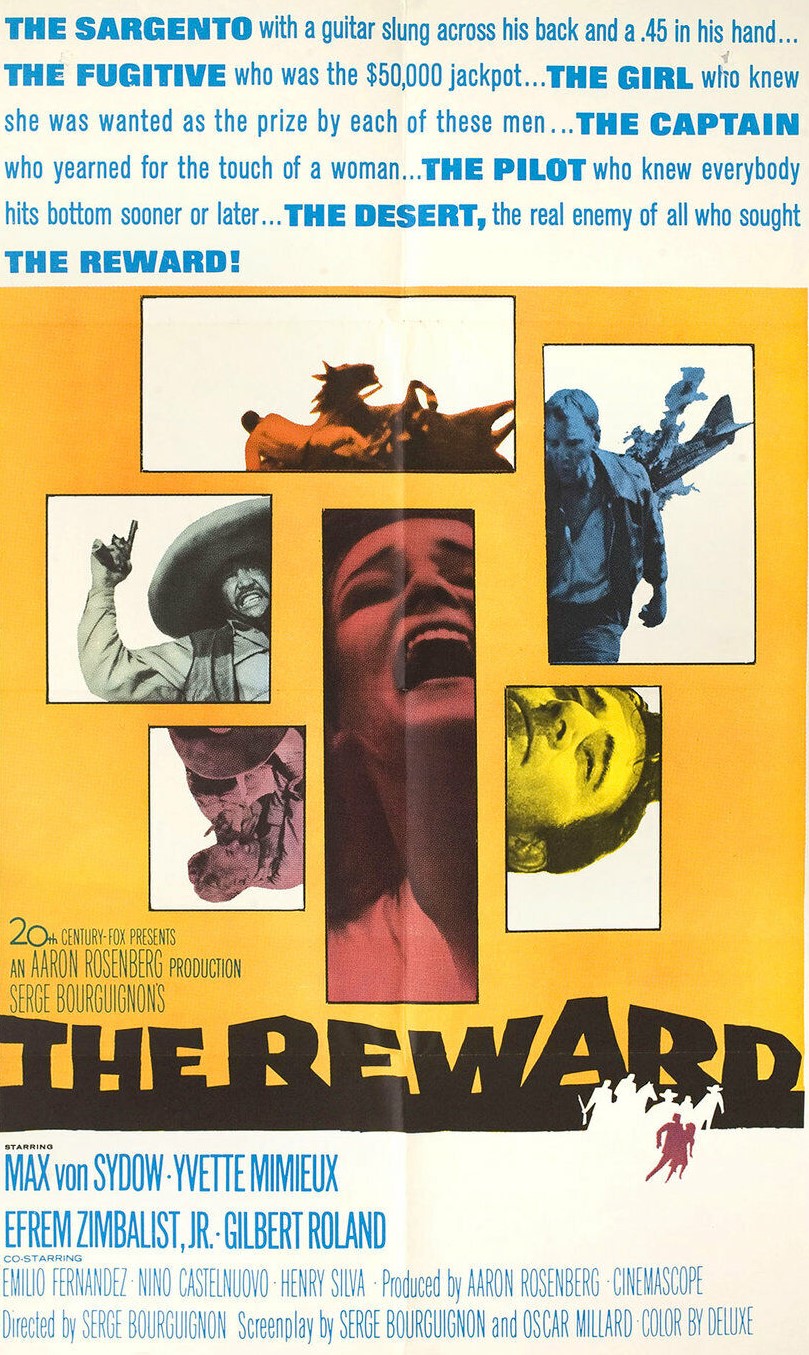

As you might have guessed this had a somewhat complicated production. Three directors were involved: Robert Sallin, Serge Bourguignon and Wes Herchendsohn. It was the only directorial chore for Sallin, better known as the producer of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982). It brought a temporary halt to the career of Oscar-nominated director Bourguignon (Sundays and Cybele, 1962) whose previous film was Two Weeks in September starring Brigitte Bardot. Herchendsohn was primarily an animation layout artist/supervisor credited with episodes of Star Trek: The Animated Series (1973-1974).

There is some stunning cinematography from Vilmos Zsigmond (Deliverance, 1972) and a superb score by Michel Legrand. This was the beginning and end of the movie career of Edwin Boyd who shared screenwriting credit with Bradbury. And it was the beginning and the end of the movie as a viable film for general release, Warner Brothers promptly shelved it.

In the hands of a French or Spanish arthouse moviemaker, with a tale of protagonists going nowhere, this might have gained more critical traction. It’s hardly going to fall into the highly-commended category, but in fact from the present-day perspective says a lot about celebrity obsession and entitlement. Despite the oddities – perhaps because of them – I was never bored.