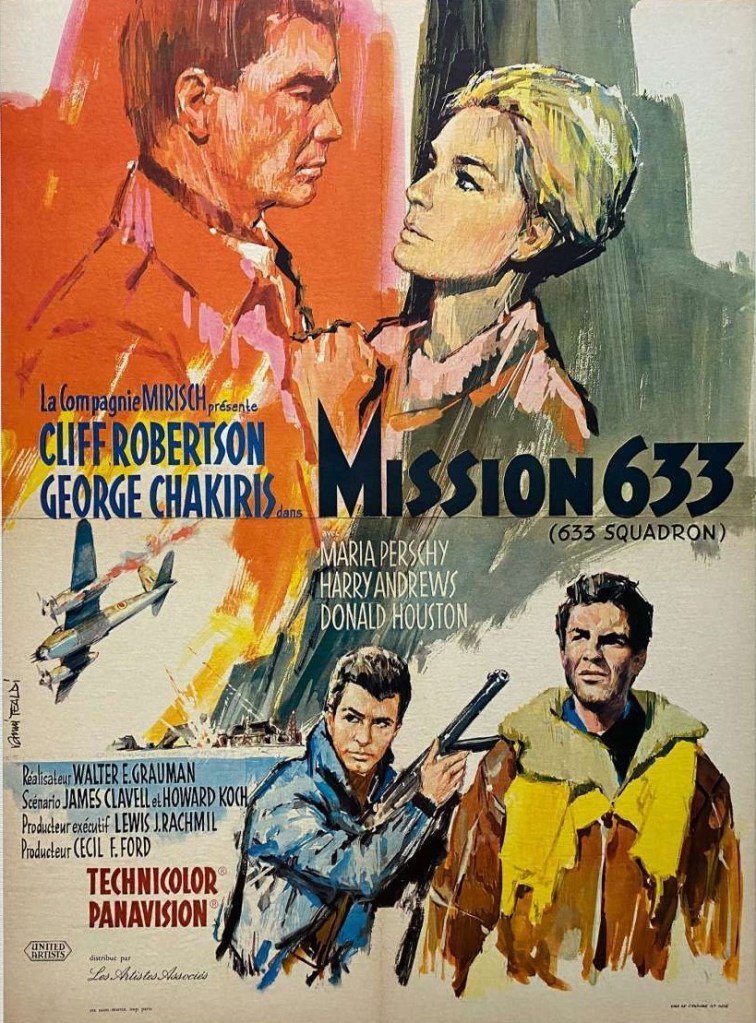

You can keep your current and future Oscar winners, George Chakiris (for West Side Story, 1961) and Cliff Robertson (for Charly, 1968). The stars here are the mechanical birds, the Mosquito bombers, and the Ron Goodwin score, a thundering rehearsal for Where Eagles Dare (1968).

The aerial photography was pretty amazing for the day, though there were no Top Gun: Maverick shenanigans with actors supposedly actually flying the planes, just sitting there with an occasional turn or yank of the controls. Even so, watching the planes take off, land, propellers describing perfect arcs, being attacked on ground or in the air, firing back, and the (apologies) bird’s eye view of dashes along precipitous cliffs takes up a huge amount of the running time.

You’ll know by now there was no actual 633 Squadron – but there was an international squadron (see the current Masters of the Air) to accommodate the various accents on show – and that the mission is also fictional, though the idea that the Germans had chosen the Norwegian fjords to hide a factory making rocket fuel for the V1s currently in production elsewhere wasn’t too far off the mark given (see The Heroes of Telemark, 1965) they were using that country for atomic bomb experiments.

The British know the rockets are inevitable, impossible to completely destroy them, but as long as they don’t interfere with D-Day that will be good enough. Wing Commander Grant (Cliff Robertson), although his squadron is exhausted from flying too many daily missions, has his leave curtailed, and told he’s on a strict deadline to destroy the factory.

Like the factory in The Heroes of Telemark, it’s virtually impossible to hit, buried beneath too much rock, but the Germans ain’t that clever, and it’s the rock that is the weakness. The theory is hit the overhang with sufficient bombs and the mountain will come tumbling down and destroy the factory.

Norwegian Resistance fighter Lt Bergman (George Chakiris) is on hand to explain just how difficult the task is, flying at extremely low altitude along fjords guarded by anti-aricraft guns. To add more tension, or just for the hell of it, Air Vice Marshal Davis (Harry Andrews) keeps on truncating the already tight deadline. The pilots have barely got time for a few practice runs along Scottish glens before it’s M-Day (no idea where that daft moniker came from, presumably a D-Day discard).

But there is just enough time for Grant to make pretty with Bergman’s refugee sister Hilde (Maria Perschy). Although after Bergman returns to help out his mates and is unhelpfully captured by the Nazis, Grant has to bomb the Gestapo building to kill him before he can be tortured and give out vital information.

In another film, Hilde would have been a spy or cut off the burgeoning romance after discovering Grant’s mission, but instead she’s not in the espionage line and she thanks the wing commander for sparing her brother torture. In the only major twist in the picture, it turns out Grant was too late, for there’s a nasty welcome committee awaiting the bombers.

Not quite the Boy’s Own derring-do adventure tale I remember, what with the torture and the climax, but it was still in my day one of the few films that appealed heart-and-soul to the pre-teen and teenage boy, along with The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape, in part, I guess, because it was so thrifty in terms of character development.

No time is wasted giving everyone a character arc, beyond the usual daredevil and someone getting married, the characters are sketchy beyond belief, but who the hell cares, let’s get on with the action. So, it certainly delivers on that score. But watching as an adult, and I’ve probably not seen this in four decades, it’s a good bit tougher than the surface might suggest, eating away at the idealism of war, of the noble sacrifice, and tuning in better than most World War Two pictures to raw finality.

Perhaps it’s emblematic that the best cinematic introduction is given to the arrival of the new-style bombs, although Hilde turning up to a torrent of wolf whistles in the bar runs it close, and she does have a habit of leaning out a window to give the audience a glimpse of cleavage every now and then.

No wonder we all came out humming the Goodwin theme. You can’t escape it. It’s in virtually every scene. Memorable final line uttering by the air vice marshal, “You can’t kill a squadron.”

It would have set the bar high for aerial photography, except that by showing how it could be done, triggered a small flurry of similar pictures, most notably The Blue Max (1966) and The Battle of Britain (1969).

Walter Grauman (A Rage to Live, 1965) clearly adores the machines more than the humans, but the script by James Clavell (The Great Escape, 1963) and Howard Koch (The Fox, 1967) based on the novel by Frederick E. Smith doesn’t give him much option.

Still worth a watch.