Ross Hunter had been a big wheel in the production business for the best part of two decades, shepherding home hits like Midnight Lace (1960), remakes of universal weepies like Back St (1961) and Madame X (1966), play adaptations such as The Chalk Garden (1964), the Tammy movie series and Julie Andrews musical Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967). He was as close to a sure thing as you could get. Even so, Airport, with a $10 million budget, was the biggest gamble of his career.

He paid $350,000 upfront plus another $100,000 in add-ons for the rights to the runaway Arthur Hailey bestseller. Initially, Hunter was targeting the roadshow audience, filming in 70mm, the first time Universal had employed Todd-AO.

Dean Martin, who had made Texas Across the River (1966) and Rough Night in Jericho (1968) for Universal, was first to sign up for his usual fee plus a percentage. Martin was at a career peak, carried along effortlessly at the box office by the Matt Helm quartet and targeted for westerns.

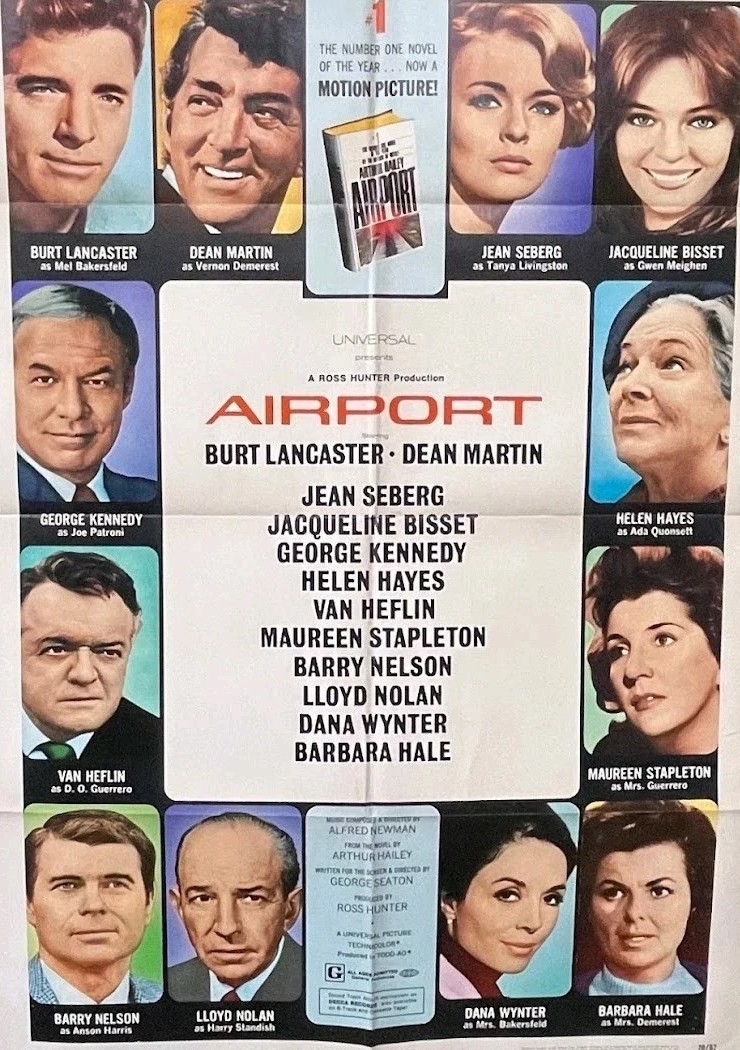

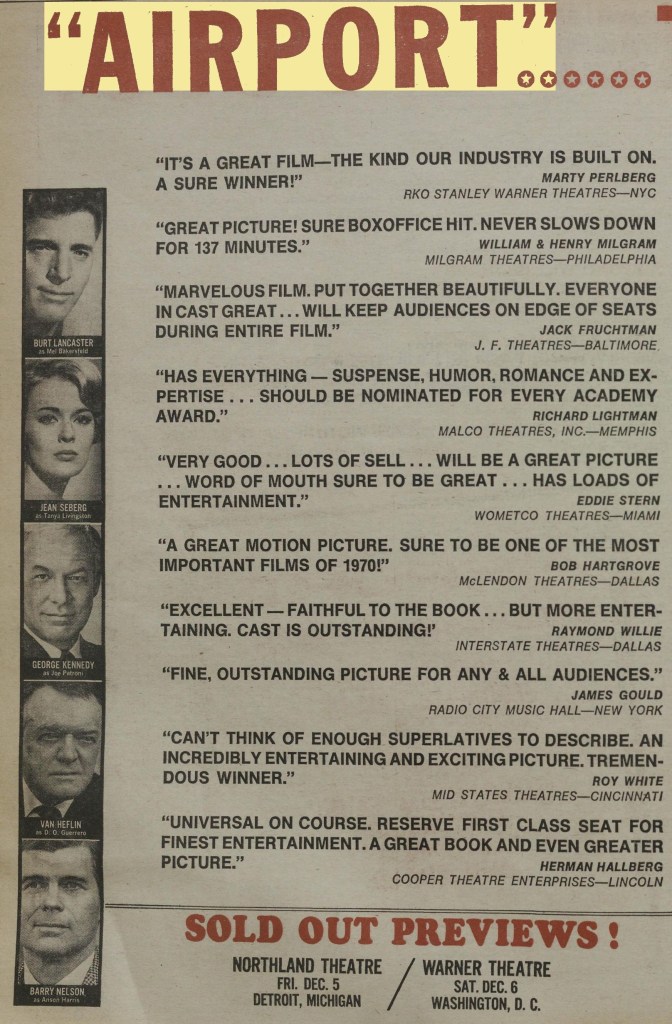

Hunter was pitching a movie with four major stars in Oscar-winner Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry, 1960), Dean Martin, Jean Seberg (Paint Your Wagon, 1969) and Oscar-winner George Kennedy (Guns of The Magnificent Seven, a1969) and another half-dozen names of varying marquee appeal that included British actress Jacqueline Bisset (Bullitt, 1968), and mature stars in Van Heflin (Once a Thief, 1965), Lloyd Nolan (The Double Man, 1967), Barry Nelson (The Borgia Stick, 1967), TV Perry Mason’s Barbara Hale and Oscar-winner Helen Hayes (Anastasia, 1956).

The picture came at a fortuitous time for Burt Lancaster. A trio of more challenging movies – The Swimmer (1968), Castle Keep (1969) and The Gypsy Moths (1969) – had flopped, so his marquee value was in question, especially at his going rate of £750,000 (plus a percentage). Doubts had set in with The Gypsy Moths, with MGM dithering over the opening date, switching it originally from summer to Xmas and then back again but happy to censor the picture to meet the approval of the Radio City Music Hall where it premiered.

And while he was still clearly in demand in 1968-1969, he had lost out the starring role in Patton (1970) with James Stewart in the Karl Malden role, which would have coupled commercial success with critical approbation. The shooting of Valdez Is Coming (1971) was postponed for a year. Originally it had been set for a January 1969 start date with Sydney Pollack directing. Face in the Dust, a Dino De Laurentiis production, never saw the light of day.

And although Lancaster later described Airport as “the biggest piece of junk ever made” (luckily he didn’t live to see Anora or Mercy), the disaster blockbuster put his career back on track. It was quite a change of pace for him, too. He wasn’t in every scene and at times he had to take whatever Dean Martin’s character threw at him. But what he brought to the picture was his natural electricity, the tension of never knowing what he was going to do. But Airport barely merits a page in Kate Buford’s biography.

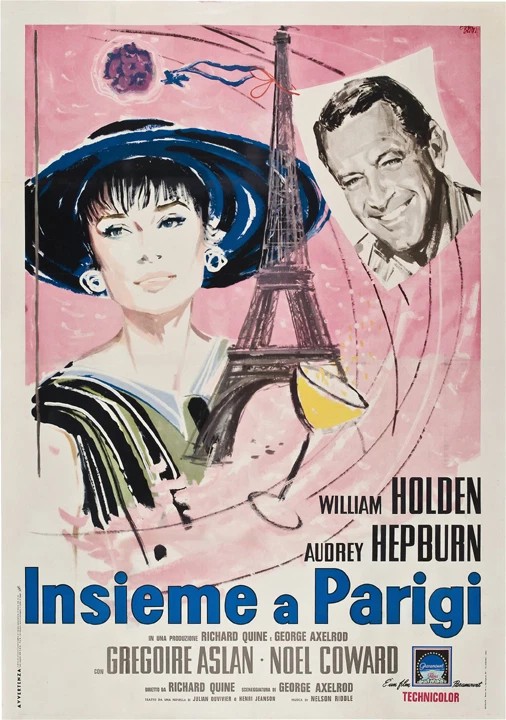

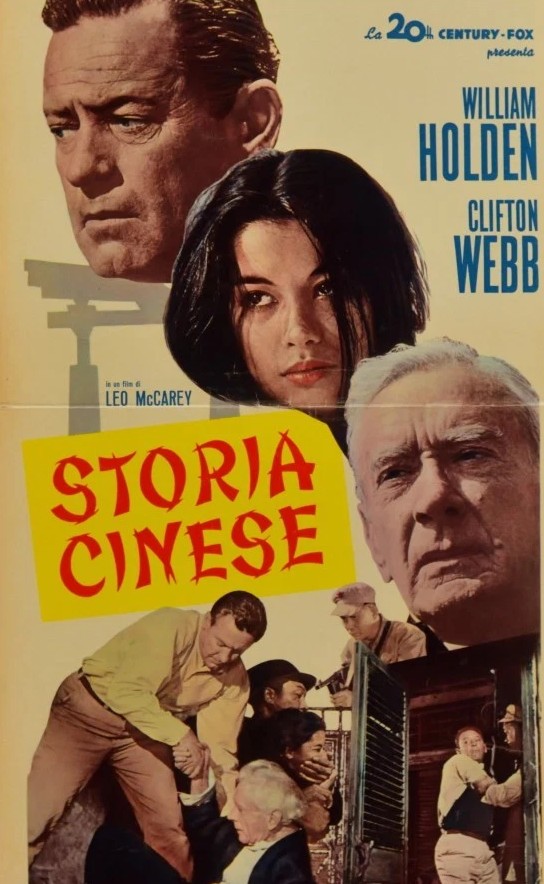

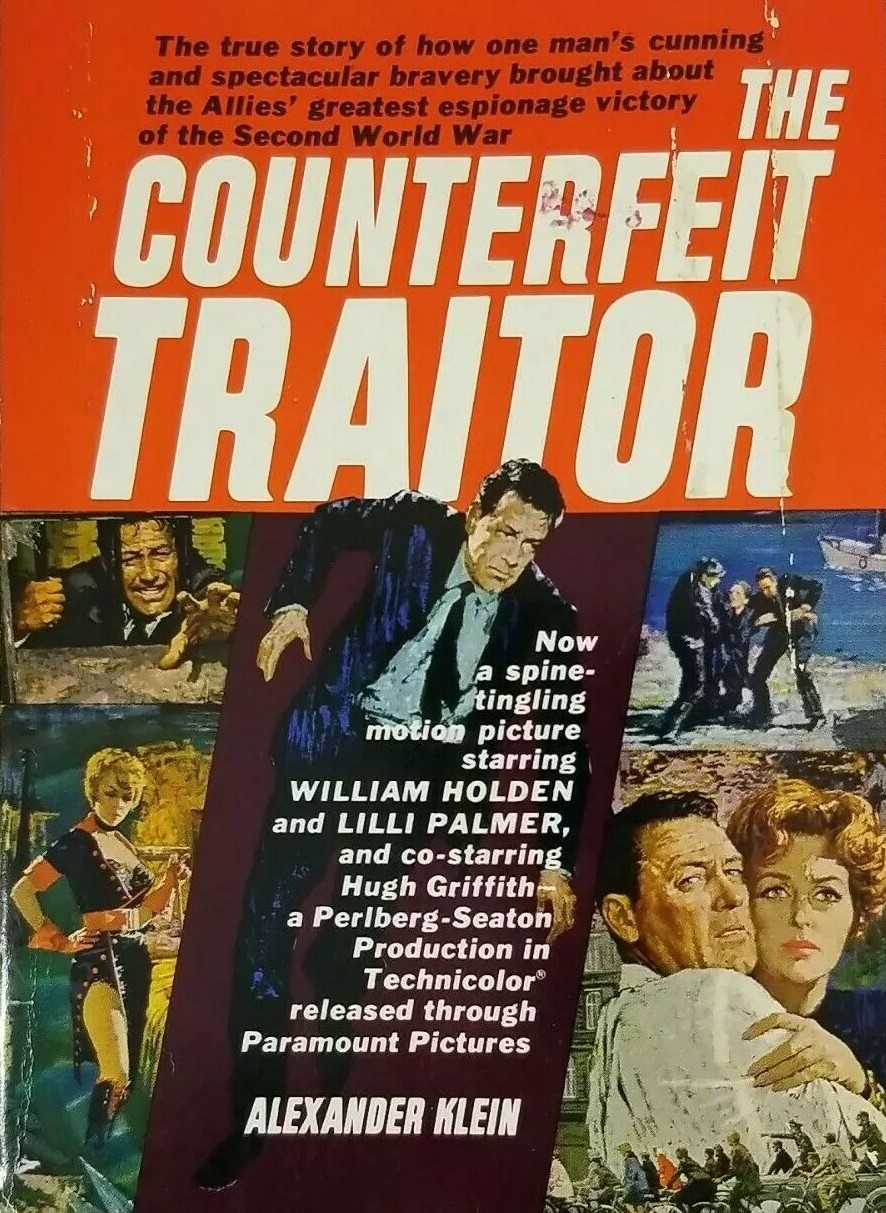

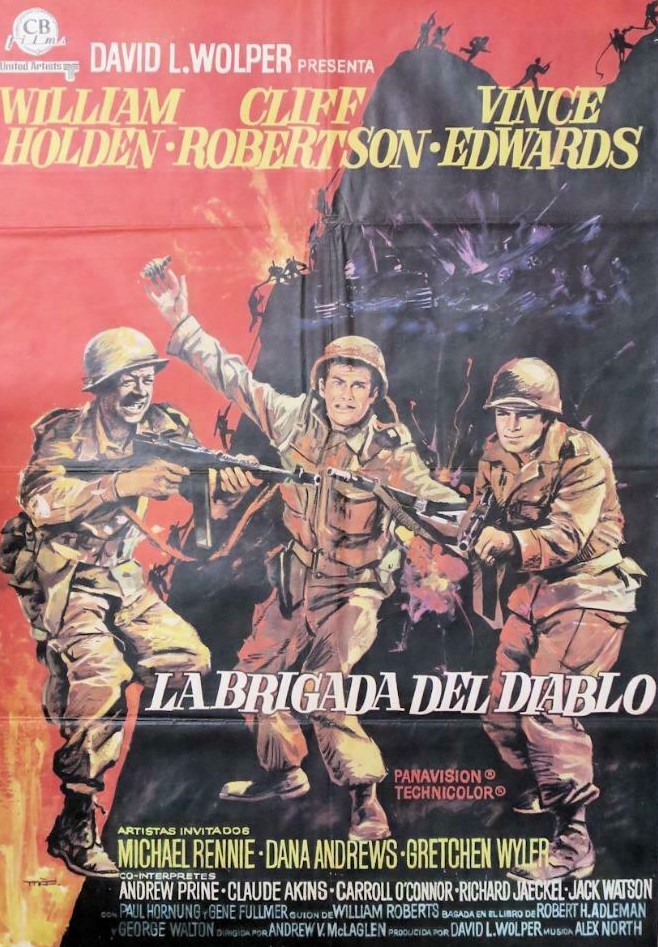

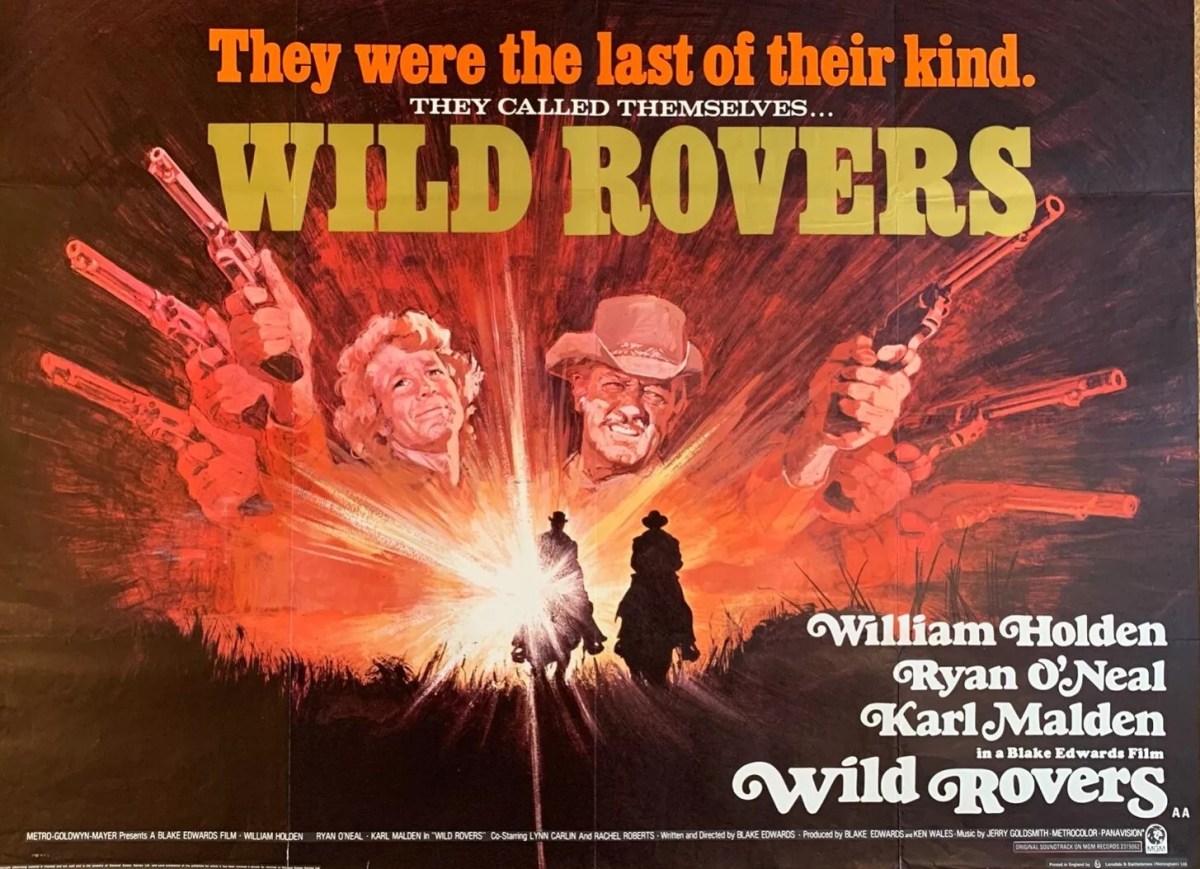

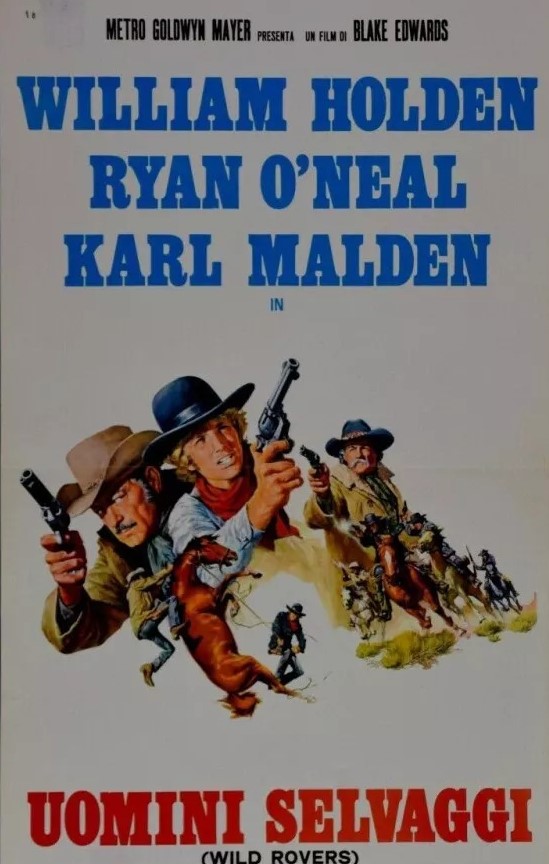

Double Oscar-winner George Seaton was set the dual task of condensing Arthur Hailey’s 500-page novel into a lean two-hour movie which he would direct. In a directing career spanning a quarter of a century, Seaton was well-used to handling big stars of the caliber of William Holden (three pictures including The Counterfeit Traitor, 1962), Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly (The Country Girl, 1953) Kirk Douglas (The Hook, 1962), Montgomery Clift (The Big Lift, 1950) and Clark Gable and Doris Day (Teacher’s Pet, 1958),

Jean Seberg, under investigation by the FBI, had revived an ailing career with Paint Your Wagon (1969). Producer Ross Hunter initially preferred Angie Dickinson (Jessica, 1962) or Stella Stevens (Rage, 1966) for the role of Lancaster’s screen lover, but had to go along with Universal with whom Seberg had a two-picture “pay-or-play” deal (she got paid whether she made a picture or not). However, she was considered a marquee name in the international market, especially France where she had remained a cult figure after Breathless (1960).

Disconcerted by being considered unwanted, her natural nervousness increased until Hunter made a point of convincing her that he was “genuinely happy” at her involvement.

She wasn’t the only person to be considered second best. For the part of the elderly stowaway, six-time Oscar nominee Thelma Ritter (Boeing, Boeing, 1965) and Jean Arthur, who hadn’t appeared in a movie since Shane (1953), had been wooed before Hunter settled on Helen Hayes.

For Seberg, it was the biggest pay cheque of her career – $150,000 plus use of a studio car and $1,000 a week expenses for the 16-week schedule, but she lost out on a percentage. She was billed third. High-flying her career might be, but personally she was struggling, her marriage to Romain Gary in trouble and under pressure to help raise funding for the Black Panther movement. She was receiving calls in the middle of the night. “Many nights she’d be so frightened, she’d come and sleep on the couch at my home,” recalled Hunter, “there’s no doubt it was an extremely difficult period for her.”

Helen Hayes reminded Seberg of her grandmother, to whom the stowaway’s exploits would have appealed. As a teenager, Seberg had idolized Hayes. Dean Martin pushed for Petula Clark (Goodbye, Mr Chips, 1969) for the Jacqueline Bisset role and Stella Stevens (Rage, 1966), as well as being considered for the Seberg part, was also in the frame.

Virtually all the bit parts were played by Universal’s contract players. For Airport, the studio rounded up thirty-two of them. Patty Paulsen, who played stewardess Joan, was a genuine stewardess for American Airlines before she won the role on the strength of winning a beauty contest. It was veteran Van Heflin’s final picture, and also for composer Alfred Newman. George Kennedy would reprise his role through three other pictures in the series – though he turned down Airplane! (1980).

Location filming at Minneapolis-St Paul International Airport began in January minus director George Seaton who had come down with pneumonia. Henry Hathaway stepped in, at no cost, to cover. The producer had headed to Minnesota for the snow, but there was none around, and the production team had to import tons of fake stuff made out of whitened sawdust. Filming took place at night in plunging temperatures. Despite wearing face masks, cast and crew suffered and the freezing conditions slowed down the shoot.

Hunter hired a $7.5 million Boeing 707 for $18,000 a day. For studio work in Los Angeles Hunter brought in a damaged Boeing. Ironically, Dean Martin had a fear of flying and travelled to the location by railway. Ditto Maureen Stapleton.

Seberg’s outfits, including calfskin sable-lined coats designed by Edith Head, cost $2,000 apiece, though Seberg was less keen on the airport uniform. With Seberg’s hometown less than a five-hour drive away she was able to head home during breaks in filming.

John Findlater, who played a ticket checker in the film, remembered Seberg as “frail and lonely…very shy…she had a very hard time of it.” It took four days to film the scene where Helen Hayes explains the art of the stowaway and feels the brunt of the wrath of Burt Lancaster and Seberg. Delays always niggled Lancaster, for whom they smacked of unprofessionalism. To raise her spirits, Seaton improvised little comedy skits.

Seberg befriended Maureen Stapleton, playing the bomber’s wife. Seberg was “impressed” that Stapleton could cry on cue and the minute the scene was over be laughing.

In the end Hunter gave up the idea of a prestigious roadshow run, settling instead for a premiere opening at the Radio City Music Hall and first run houses across the country. There had been no shortage of pre-publicity. Any time an airplane hijack hit the headlines or a snowstorm shut down airports or an airplane skidded off the runway, editors were happy to insert a mention of the picture.

And there was an abundance of airports and travel companies willing to sign up for cooperative promotions, helped along by the fact that Edith Head had designed the “Airport Look” launched not just with male and female fashions but a range of travel accessories. A beauty queen competition “International Air Girl” managed to hook a 45-minute television slot in Britain.

Opening at the Radio City Music Hall in New York, a couple of weeks in advance of the national roll-out, Airport plundered a record $235,000, topping that in its second week, and scooping up $1 million before the end of the month. It was gangbusters everywhere, opening in prestigious first run locations, with nary a showcase/multiple run in sight. “Wham” was the description beloved of the Variety box office headline writers, the word preceding its $80,000 opening week tally in Chicago, $28,000 in San Francisco, and $25,000 in Louisville. “Smash” was also brought into play for its $40,000 in Baltimore and $33,000 in Philadelphia. The subject matter allowed the sub-editors who wrote the headlines some license, so it was a “sonic” $40,000 in Boston and a “stratospheric” $45,000 in Detroit. And it had legs. Week-by-week fall-offs were slight. It was still taking in $25,000 in the 24th week in Detroit, for example.

By year’s end it was easily the top film of the year with $37 million in rentals, way ahead of Mash on $22 million and Patton $1 million further back. And it kept going, adding another $8 million the following year as it was dragged back into the major cities for multiple showings (seven in New York) in multiple engagements.

Business was not so robust abroad. Though Airport managed a six-week run at the Odeon Leicester Square, where it received a Royal Premiere on April 22, 1970, its opening week’s figures were down on both the final week of its predecessor at the London West End cinema, Anne of the Thousand Days, and its successor Cromwell and the film didn’t make the Annual British Top Ten. But in Australia it led the field, though its returns were one-third down on the previous year’s Paint You Wagon and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

For its television premiere on ABC in 1973, the network demanded a record $140,000 per minute for advertising. Outside of Gone with the Wind, it earned the highest rating of any movie from 1961 to 1977.

But it also set up an industry. Sequels were the name of the game. And though Airport ’75 (1974) headlining Charlton Heston and Airport ’77 (1977) starring Jack Lemmon were cut-price operations, they were huge successes at the box office, the former hauling in $25.8 million in rentals, the latter $16.2 million. A fourth venture, The Concorde…Airport ’79 (1979) with Alain Delon, flopped and put an end to the series.

SOURCES: Garry McGee, Jean Seberg, Breathless, 2018, p167-171; Kate Buford, Burt Lancaster, An American Life (Aurum Press, 2008) p264-265; “Cast Patton & Bradley,” Variety, September 20, 1967, p13; “Airport Film Deal,” Variety, May 29, 1968, p60; “Steiner at Goldwyn Plant,” Variety, July 24, 1968, p7; “Dean Martin First to Sign for U’s Airport,” Box Office, August 5, 1968, pK4; “Hollywood Happenings,” Box Office, January 6, 1969, pW2; “Airport Will Be U’s First Feature in Todd-AO,” Box Office, January 13, 1969, p12; “Seaton’s Temp Sub at U: H. Hathaway,” Variety, January 22, 1969, p7; “Airport Sequence Follows Real Event,” Box Office, January 27, 1969, pNC3; “17 Inches Snow Brings North East Business To Complete Standstill,” Box Office, February 17, 1969, pE1;“Ross Hunter’s Roadshow,” Box Office, April 28, 1969, pK2; “De Laurentiis Slates 3 Aussie Locationers,” Variety, September 24, 1969, p18; “Put Back Moths Scenes Cut Solely for Radio City,” Variety, October 22, 1969, p5; “Airport Smacks $1-Mil,” Variety, April 1, 1970, p4; “Airport Contest on TV,” Kine Weekly, April 18, 1970, p18; “Big Rental Films of 1970,” Variety, January 6, 1971, p11; “Encore Hits,” Variety, June 16, 1970, p5; “ABC Flying 140G Per Minute for Airport,” Variety, June 27, 1973, p14; “Hit Movies on TV Since ’61,” Variety, Sep 21, 1977, p70; “All-Time Film Rental Champs,” Variety, May 12, 1982, p5. U.S. weekly box office figures – Variety, March-April 1970; U.K. weekly box office figures, Kine Weekly, April-July 1970.