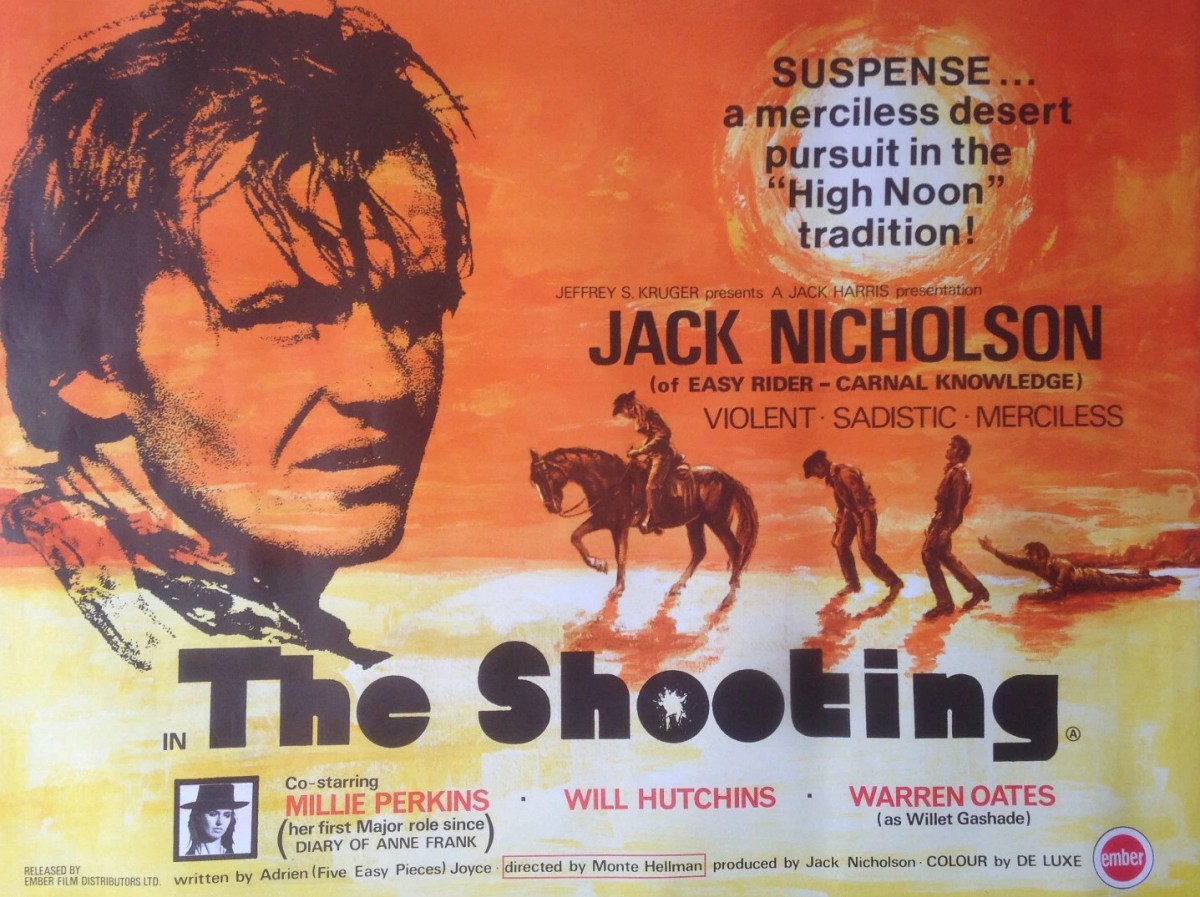

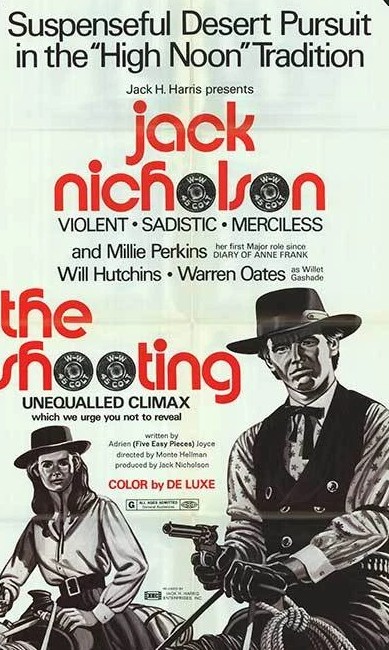

Director Monte Hellman struck lucky three times. In the first place French critics took such a shining to this disjointed elliptical western that they tabbed it a work of existential genius. Then Jack Nicholson, who only has a small part, became a global star and it picked up a second head of steam. And now, with grief porn the latest craze thanks to the likes of Hamnet (2025) and Wuthering Heights (2026) I reckon it’s worth reassessment. But not for that wallowing in grief aspect so popular these days, but for the way genuine grief works its way out in cantankerous maddening fashion.

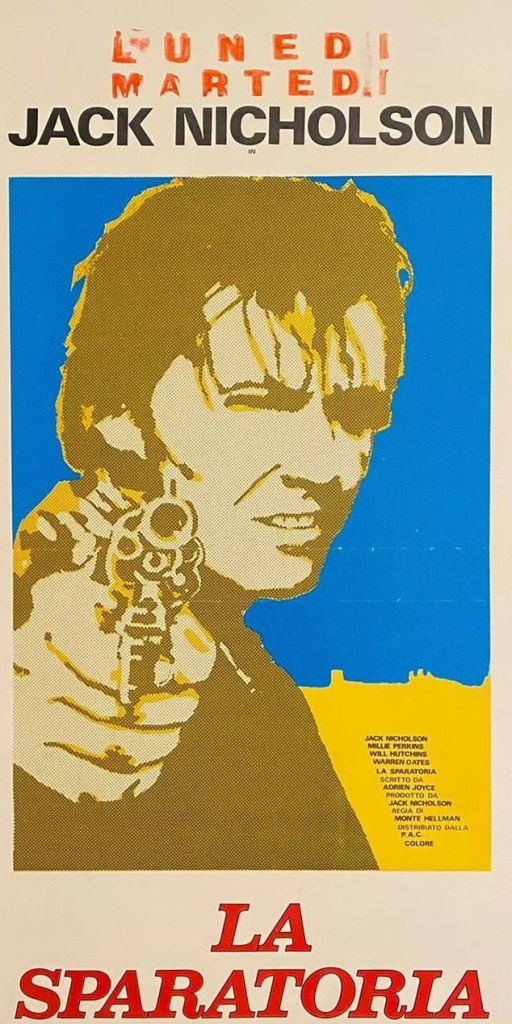

You’d have thought the performance of Millie Perkins would have been highlighted long before now for its feminism. Her un-named woman runs contrary to the notion of the female star in a western. She doesn’t come on all sexy in a Raquel Welch fashion, nor does she fall victim to a predatory male. But she is a heck of a creation.

She doesn’t play by any of the man-made rules in this male-dominated world. She gets what she wants by foul means and she doesn’t give a hang about whose feelings she tramples underfoot. She’s not interested in seduction, nor in finding a man, so strike out any thoughts of sex or romance, and she’s domineering, rude and contrary.

Given the western is weighted down with enigma, you have to work hard to find out what it’s all about and what’s she’s after. And her introduction tells you she’s trouble. She kills her own horse so she can appear to two cowboys running a defunct mine as a woman needing help. The younger Coley (Will Hutchins) would be easily duped by any woman with an ounce of the smarts. The older Willett Gashade (Warren Oates) is less easily led, though when the woman offers $500 if they help her reach the nearest town, they’re ready to oblige.

But she wants to make haste, while Willett wants to ensure they are equipped for the journey, so saddling up an extra mule to carry their supplies. But a mule slows them down, so she finds a way to stampede it off. And every now and then she lets off a random shot, Willett working out she’s trying to attract someone’s attention. The someone turns out to be gunslinger Billy Spear (Jack Nicholson). When she insists on going off-trail Gashade works out she’s hunting for someone.

That’s another elliptical moment. She’s hunting the killer of her son. Even though it was an accident, she wants revenge.

And that’s the grief spelled out in a variety of ways but never with the usual emotional baggage, not even a tear. Eventually, we’re in Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) territory where men are going mad. Here, they keep going after their horses die and trek over desolate merciless country until they find their quarry, who turns out to be Gashade’s brother.

Turns out, too, she hardly needs her entourage. She finishes off her nemesis while Spear and Gashade struggle behind. She only needed the men for their tracking skills.

So what we have instead of the existential is something considerably more solid and worth far more than falling in with some arthouse accolade. This is both an exceptional study of grief and an exceptional study of a woman, possibly the first in the feminist line if you discount Barbara Stanwyck who still, generally, was better off with a man at her side.

All her deriding of the men, her mental cruelty, her whimsical actions, make every bit of sense when you realize these are all expressions of grief. Except for her murderous intent, she’s almost stoical in her grief, never allowing wanton emotion to get in the way, and even when turning tearful might work in winning men over she doesn’t give in to the temptation. She can twist Coley round her little finger anyways and she knows how to handle Gashade, teaching him in no uncertain terms who’s boss.

In some respects Monte Hellman (Ride the Wild Whirlwind, 1966) is the inheritor of the Budd Boetticher mantle, purveyor of lean westerns short on running time with a principled hero, here read heroine. But Hellman lacks Boetticher’s compositional artistry and could do with putting some more work into the storytelling department.

If you’ve come looking for the Jack Nicholson of Chinatown (1973) you’ll be disappointed. He’s hardly in it, though he is an exemplar of that mantra in The Housemaid (2025) of teeth being a privilege. Warren Oates (The Wild Bunch, 1969) is a better bet, providing a foretaste of his grizzly characters to come.

But Millie Perkins (Wild in the Streets, 1968) tears up the screen. From her bold introduction to the savage conclusion she presents a vivid characterization of a woman expunging her grief with violence. Written by Carole Eastman (Five Easy Pieces, 1970).

Well worth a look.