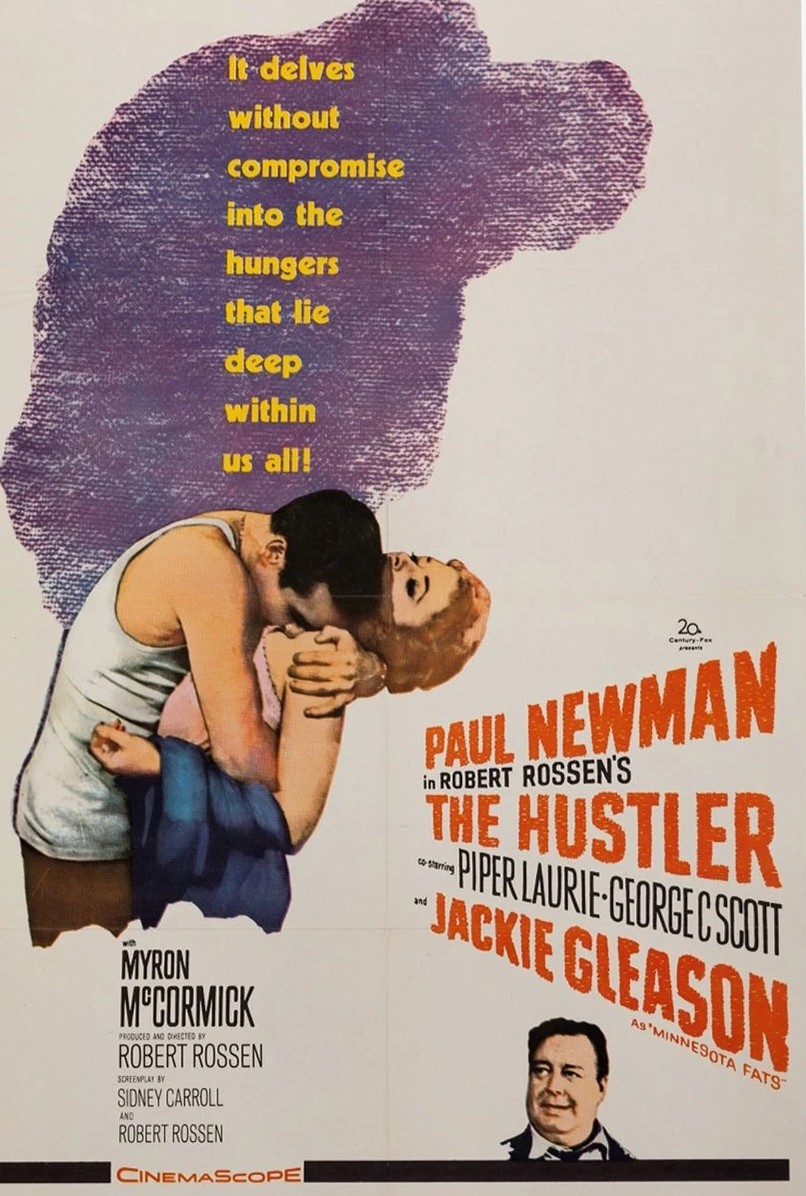

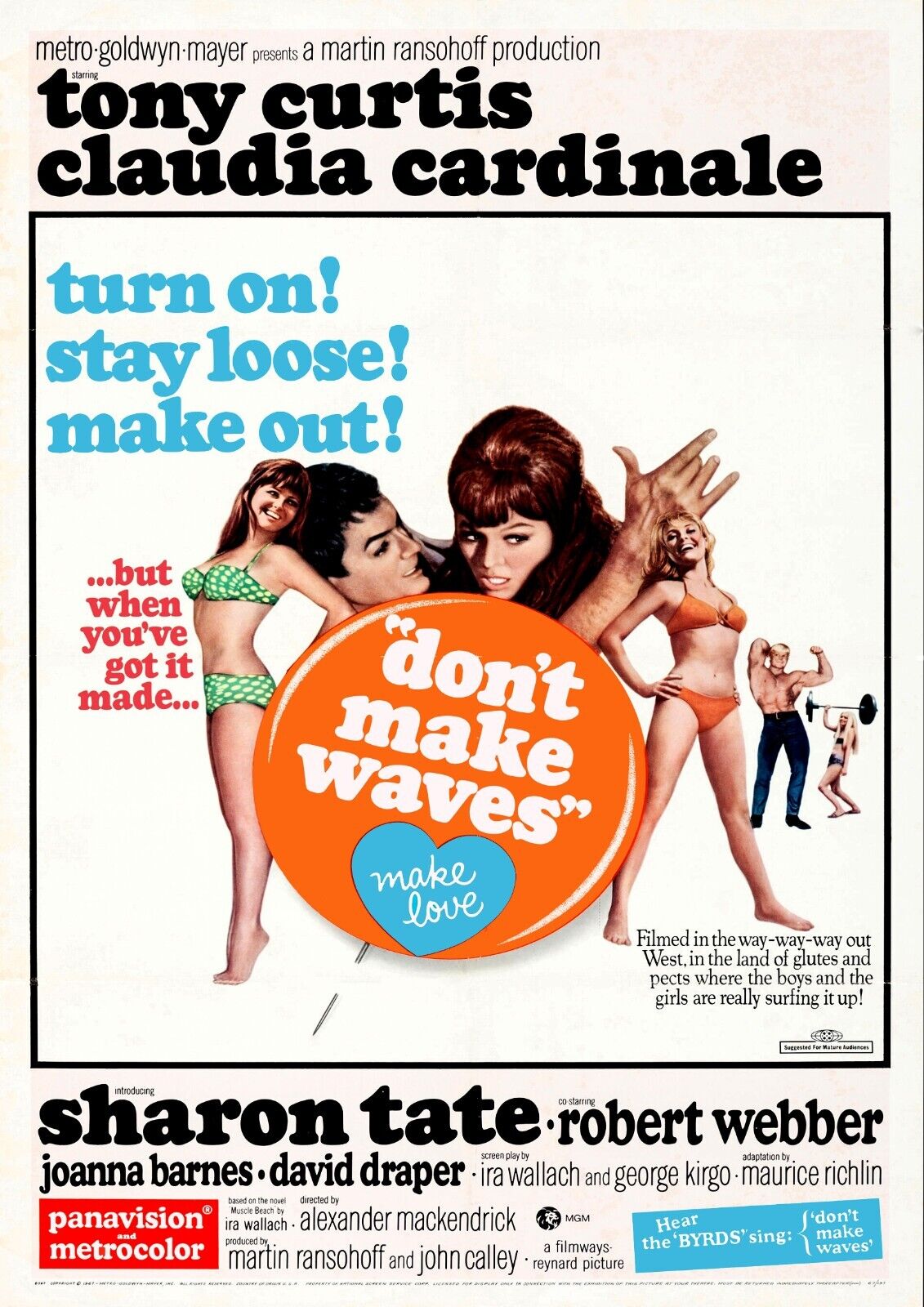

While Twentieth Century Fox head honcho Spyros Skouras initially balked at the title, with its connotations of prostitution, by the time the movie appeared that subject matter was less contentious thanks to critical and commercial big hitters Butterfield 8 (1960) and Never on Sunday (1960). Given that the idea of a movie set in a poolroom was going to be a hard sell to a female audience, despite the marquee lure of Paul Newman, the studio gave marketeers free rein to pitch it as a raw, sex-oriented drama.

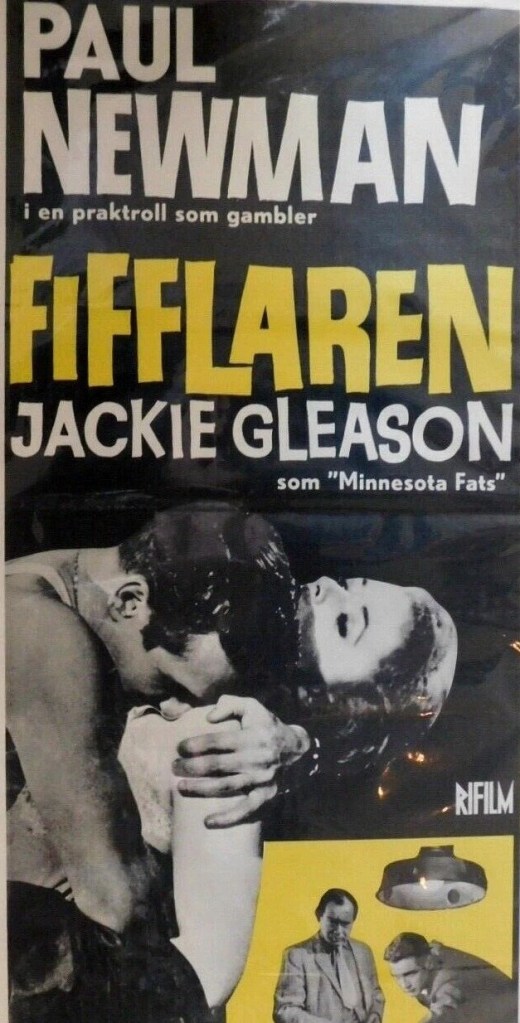

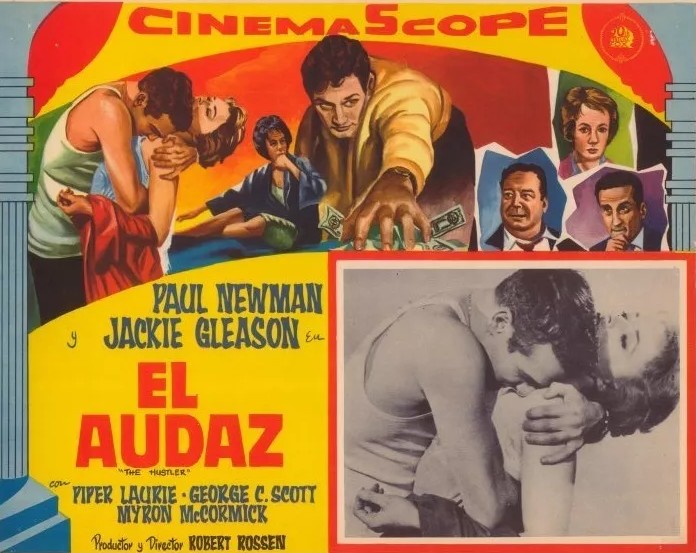

There’s little sign of a pool cue in some of the artwork. Instead, we have Paul Newman lustily nuzzling Piper Laurie’s neck or bosom. The taglines promise something far removed from a sports picture.

“It probes the stranger…the pick up…the savage realities,” screamed the main tagline. Another tempted with: “It delves without compromise into the inner loneliness and hunger that lie deep within us all!” In other words we’re talking about sex, not love, and casual sex at that, the world of the one-night stand between consenting adults for whom marriage is the last thing on their minds. “The word for Robert Rossen’s The Hustler is prim-i-tive” suggested out of control lust.

Fast Eddie Felson (Newman) has “the animal instinct.” Sarah (Piper Laurie) has a “bottle, two glasses and a man’s razor always in her room.” Bert (George C. Scott) is on the look-out for the “sucker to skin alive.”

Those images which did show a cue and pool balls did not suggest an august sport like football or baseball, not with a tagline like “he was a winner, he was a loser, he was a hustler.”

With such talented actors to hand, the Pressbook wasn’t short of good stories relating to the actual movie rather than the kind of snippets that might appeal to an editor on a slow news day. So we learn that Piper Laurie continually limped, Method-style, around on the set. “When I limp in the picture, I don’t want to act it. It’s something that has to be a part of me, something of which I am no longer conscious, apart from its being a physical defect. I must be able to limp as if I had a bad foot from birth.”

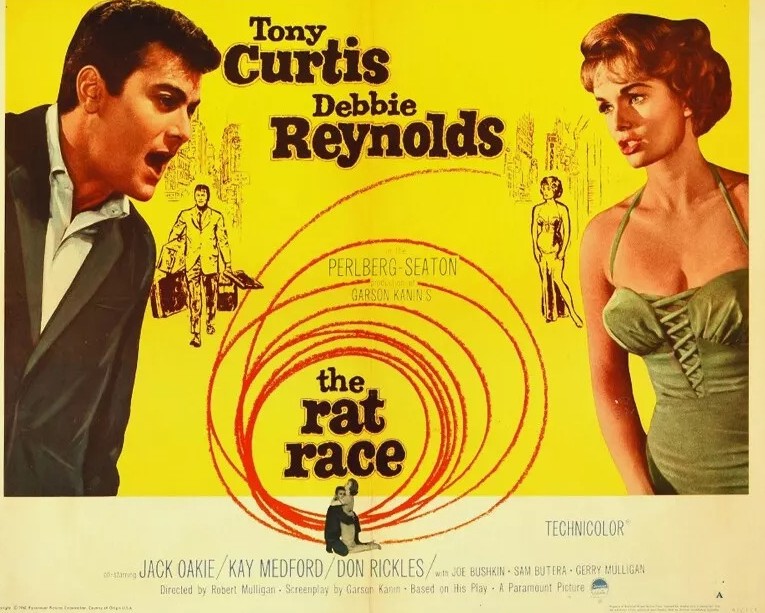

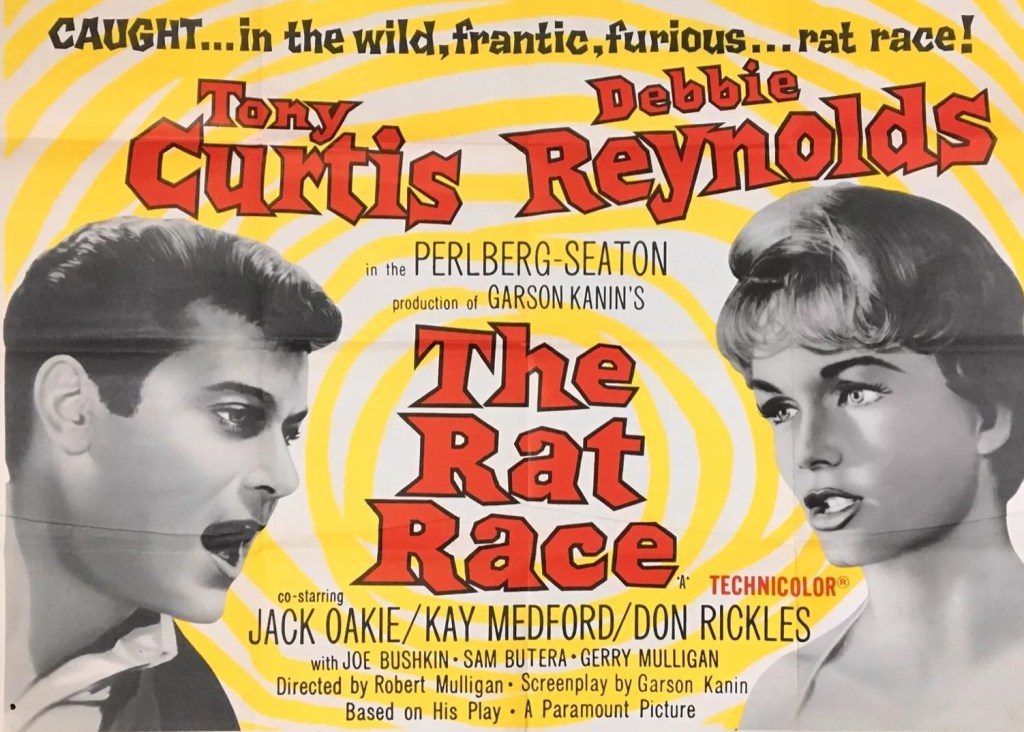

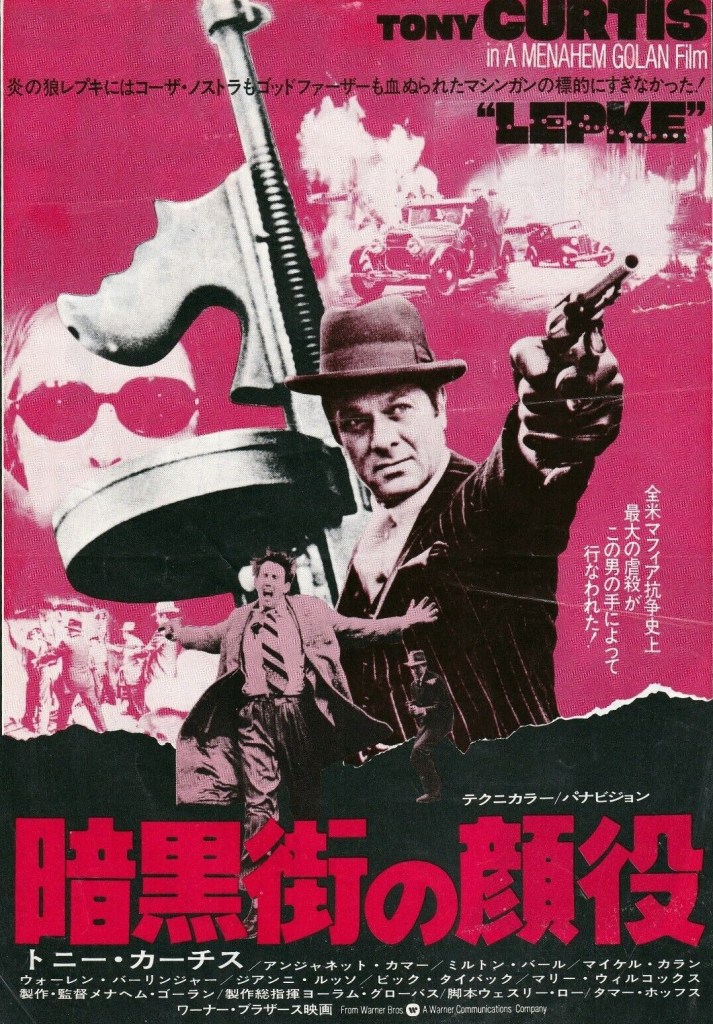

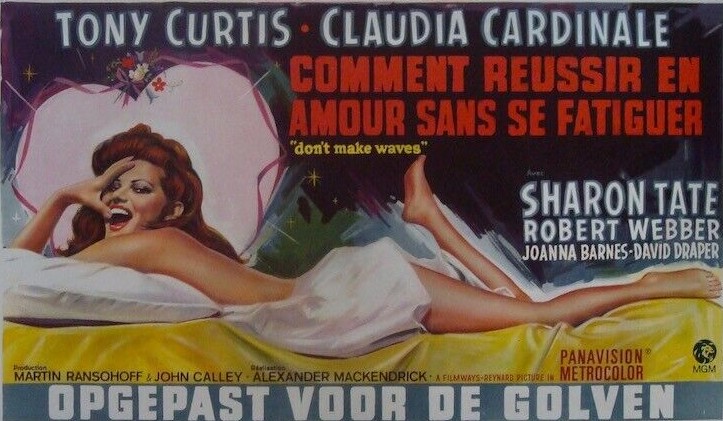

Laurie had made so few pictures that her name wouldn’t be on any director’s wanted list and what she was best known for – ingénue roles when a contract player for Universal (who gave out that she bathed in milk to keep her skin soft) opposite the likes of Tony Curtis – wouldn’t have inspired confidence. Robert Rossen might well have spotted her in two Emmy-nominated performances in successive years including Days of Wine and Roses (1958), but instead said he remembered her for “a sensitive characterization” from a stage production of Rosemary.

Ames Billiards Academy had once been a Chinese restaurant so boasted a balcony. This was unseen in the picture but allowed director Robert Rossen to shoot from widely varied overhead angles. The crew took over the Manhattan Bus Terminal for a day and a night. A row of lunch booths was constructed in front of the existing lunch counter. “It looked so real,” we are told, “that passers-by sat down and waited for their orders to be taken.” A nice story, and the kind often furnished by Pressbook journos, but rather fanciful, since it would be obvious what with the crew milling around and the lights and cameras and miles of cable that this was a movie set with security posted to prevent trespassing.

Just how good a pool player was Jackie Gleason, who came to the picture with a reputation for handling a cue? Well, at one point, the affable television comedian with a top-rated show, potted 96 consecutive balls.

Paul Newman plays the iconic hero as a “figure cut from the fabric of our time.” He had a firm grasp of the character. “With him it’s a question of commitment. He is so wrapped up in his drive to win and be somebody that he has no time to give of himself that which others need. It is a disease of our time, both the ambition and the isolation. I want him to be understood.”

Needless to say there was no mention of author Walter Tevis. That wasn’t so unusual in the make-up of Pressbooks, but if the marketeers these days were looking for something to write about the eclectic Tevis would be prime. He followed up The Hustler, published in 1959, four years later with sci fi The Man Who Fell to Earth, filmed in 1976 with David Bowie. A sequel to The Hustler, The Color of Money, was directed in 1986 by Martin Scorsese with Newman reprising his role and managing Tom Cruise. Tevis also wrote The Queen’s Gambit, turned into an acclaimed television mini-series in 2020 with Anya Taylor-Joy.