Of the 25 million stories you could have chosen when New York and the surrounding area was hit by an electricity blackout in the mid-1960s, you could have elected for something more interesting than this farce-style comedy that after the opening sections resembles nothing more than a stage play. But that’s because, somewhat surprisingly, it is based on a play and one concerning not the great fracas in the Big Apple but a similar occurrence in Paris almost a decade before. Once you know that, the farce element makes sense, but not much else does.

The three constituent parts that eventually coalesce into little more than a collage of double takes and startled expressions are: thwarted businessman Waldo (Robert Morse) making off with a couple of million bucks; Broadway star Margaret (Doris Day) finding architect husband Peter (Patrick O’Neal) in a clinch with journalist Roberta (Lola Albright); and impresario Ladislaus (Terry-Thomas), the most English-sounding Eastern European you ever came across, terrified Margaret is going to quit his play.

The lights going out malarkey is an ill-judged MacGuffin so that all except Roberta can end up in a classy Connecticut apartment and get into a quandary about who loves who and who’s cheating on who and career choices to be made. It’s pretty hard work all round to make all the pieces misalign and then fit. Waldo’s car has broken down so he has no real reason to be there nor to gulp down a beaker of alcohol that knocks him out without noticing that Margaret is fast asleep on the same couch after imbibing the same concoction.

Cue not much hilarity when guilty Peter turns up hoping to win back his wife, not expecting to find her unconscious from booze and once he discovers her bed partner convinces himself that she is as much of a cheat as himself. Meanwhile, Ladislaus tries to keep the jealousy pot boiling in the hope that she will divorce her husband and be forced to continue working.

I’m not sure I really cared whether it all worked out or not. Sure, comedies often pivot on bizarre instance, but this is just awful. More to the point, the structure doesn’t focus sufficiently on Margaret. The Waldo scenario seems wildly out of place and not enough is made of the chaos of the blackout. More to the point, with streets completely jammed and traffic signals not working, just how all four manage to get out of the city is beyond belief.

Sure, Doris Day grew up fast in the decade; at the start we worry about her losing her virginity; by the end it’s whether she’s going to embark on an affair. She’s always on the brink of the kind of sophistication that might tolerate an affair before drawing back in shock at such a notion.

The laffs are thin on the ground, even Doris Day drunk – one of her trademark touches – seems to lack punch. The best written scenes are those between Ladislaus and his cynical psychiatrist

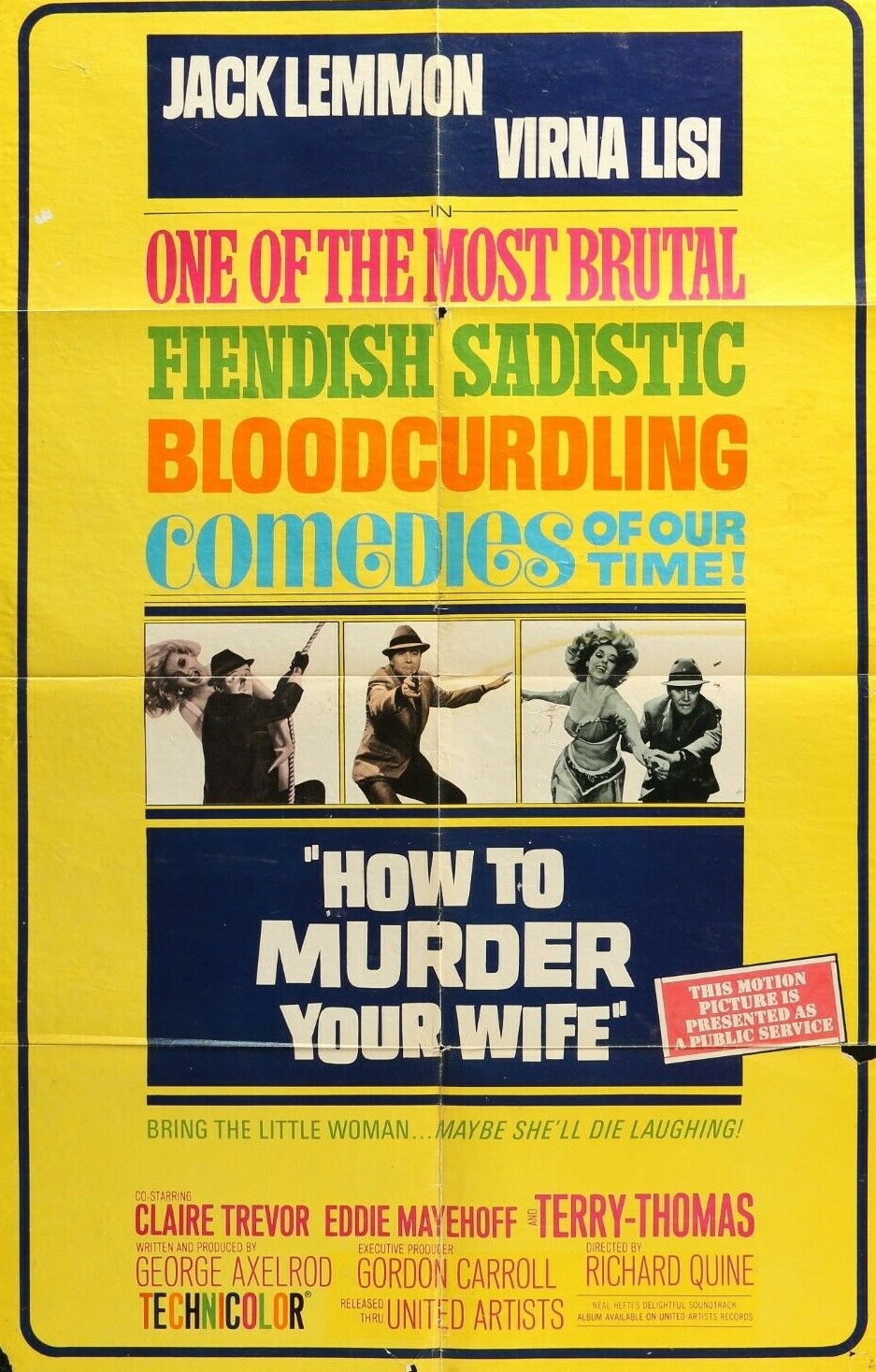

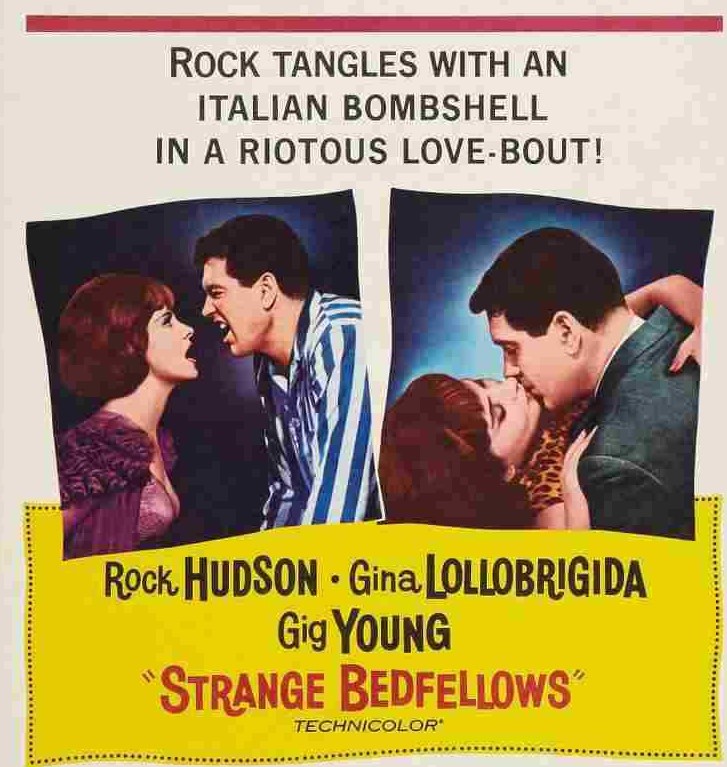

Doris Day does her best but it’s far from the sparkling form of Pillow Talk (1959) that kicked off her very own rom-com subgenre. The quality of her male co-star had diminished over the years, from the peaks of Rock Hudson and Cary Grant to the acceptable Rod Taylor and James Garner but Patrick O’Neal (Stiletto, 1969) acts as if he is curling his lip and about to belt someone in the harder-edged dramas with which he made his name. Robert Morse (The Loved One, 1965) looks as though he’s still trying to work out what his character’s doing there. However, Terry-Thomas (Arabella, 1967) exudes such charm he’s always a joy to watch. Lola Albright (A Cold Wind in August, 1961) isn’t in it nearly enough.

The original French play by Claude Magnier was a sex farce, but casting Doris Day meant the sex angle was played down, inhibiting the movie. An unlikely vehicle for screenwriter Karl Tunberg – Ben-Hur (1959) and Harlow (1965) – who co-wrote with producer Everett Freeman (The Maltese Bippy, 1969). Director Hy Averback (The Great Bank Robbery, 1969) doesn’t come close to demonstrating the lightness of touch required to make such a ponderous effort work.

File under disappointment.