Soubriquets were not common currency in Hollywood. Names might be shortened to a Christian name or a surname, as in Marilyn or Garbo, and occasionally a reporter might suggest an unlikely familiarity by referring to a star as “Coop” and for sure Bogie must have been desperate for people to call him anything other than Humphrey, hardly a name that spun off the tongue for a supposedly hardbitten hero eschewing his middle-class origins. But the world swung on its axis when simple use of the star’s initials were enough to guarantee universal acceptance.

BB was born on a wave of controversy. After And God Created Woman (1956) broke box office records all over the world, a star was born. But one who seemed to live as much on the pages of newspapers as on the screen. She could forever be guaranteed to provide a revealing photograph to spice up the more puritan newspapers.

But BB’s global fame didn’t translate into worldwide box office in part because her movies were mostly X-certificate in the U.K. and, being made generally by foreign companies, slipping past the Production Code in the U.S. and therefore into arthouses or shady emporiums in both countries rather than mainstream houses.

This isn’t the best introduction to her canon, but in many senses it’s pretty typical. The camera adores BB and shuns anyone else in her presence. There’s not much story here – bored wife dashes off to a model assignment in London and has an affair and can’t decide whether he’s ready for divorce.

To fill in the time we get plenty Carnaby St fashion shoots, certainly put into the shade by the likes of Blow-Up (1966), but of the kind that used to be so common, beautiful women in outlandish clothes against backdrops like zoo animals or suits of armor and all the while flirting with photographers and being chatted up in night clubs by all and sundry. As you might expec, red buses and mini cars are common, though the chances of a cop on horseback at night seems to stretch it a bit.

Cecile (Brigitte Bardot) seems too lively for staid husband Philippe (Jean Rochefort) and burdens him with ensuring her happiness. But he seems, I guess unusually for the time for such a wealthy character, to be happy for her to continue in her profession. She’s never been unfaithful unlike model buddy Patricia (Georgina Ward). But all this cavorting brings out the lech in photographer Dickinson (Mike Sarne) and while she flirts with him she fancies for no apparent reason the doe-eyed Vincent (Laurent Terzieff) although his doe-eyed dog is livelier.

Anyway, off they go to Scotland for a romantic idyll since every filmmaker in the world has been duped by Scottish Tourist Board fantasies of sunshine, tartan, heather and miles of unspoiled beaches (unaware they are empty because the natives have more sense than to go diving into icy water in freezing temperatures). Mostly, what they get is damp streets and grey skies, though if you have BB romping in the water then nobody’s really going to notice the awful weather. And, naturally, the highways and byways are filled with tartan-clad gents so Brigadoon rides again.

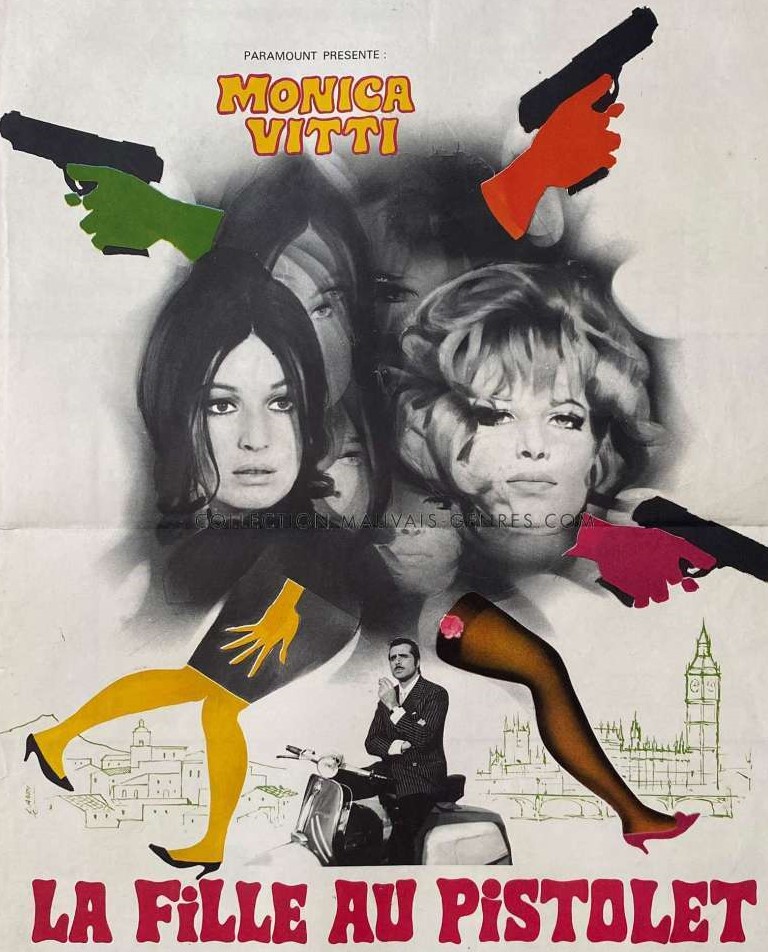

is turned into the dull “Two Weeks in September.” Though she hardly seems happy in the poster.

In any case, by the time September comes round, the sun has already packed up for the winter in Scotland, so there’s your get-out-of-jail-card in the title. Not much happens in Scotland either, mostly soulful camera work, soulful BB and dull-as-ditchwater Vincent. There’s a contrived ending.

What impresses most is how little BB you need to make a picture work, even one as patchy as this. It is almost the same template as an Elvis picture minus the songs. Just like BB, Elvis scarcely required a working script, just any excuse to get him on screen. Some stars possess screen charisman that it’s impossible to shift. Shame it was left to Serge Bourguignon (The Picasso Summer, 1969) to get more out of the faint storyline because he was never that bothered with narrative and inclined just to get by on close-ups and scenery. With BB she was as much scenery as audiences ever seemed to require.

Hardly falls into the recommended bracket but nonetheless an interesting example of how Bardot could get away with the mildest of trifles.