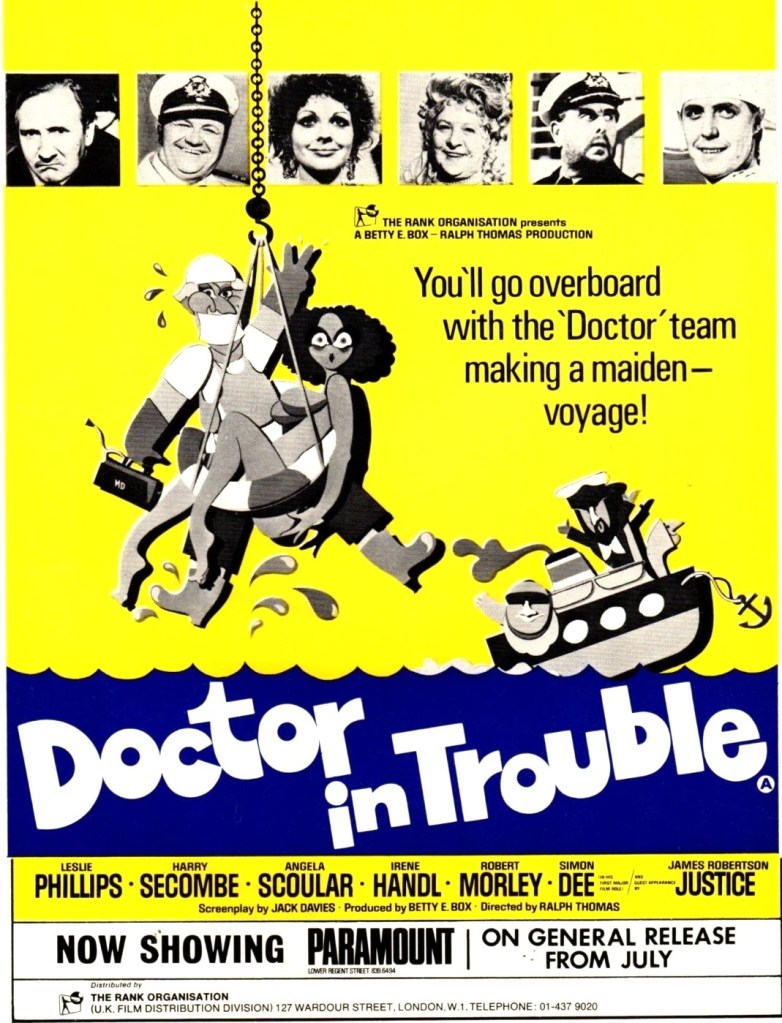

Limp ending to a fine series. Torpedoed by too many oddities. Leslie Philips returns in the top-billed role, but he’s not playing the suave Dr Gaston Grimsdyke of the previous iteration, but instead a more hapless version of Dr Paul Burke, the character he played a decade before in Doctor in Love (1960).

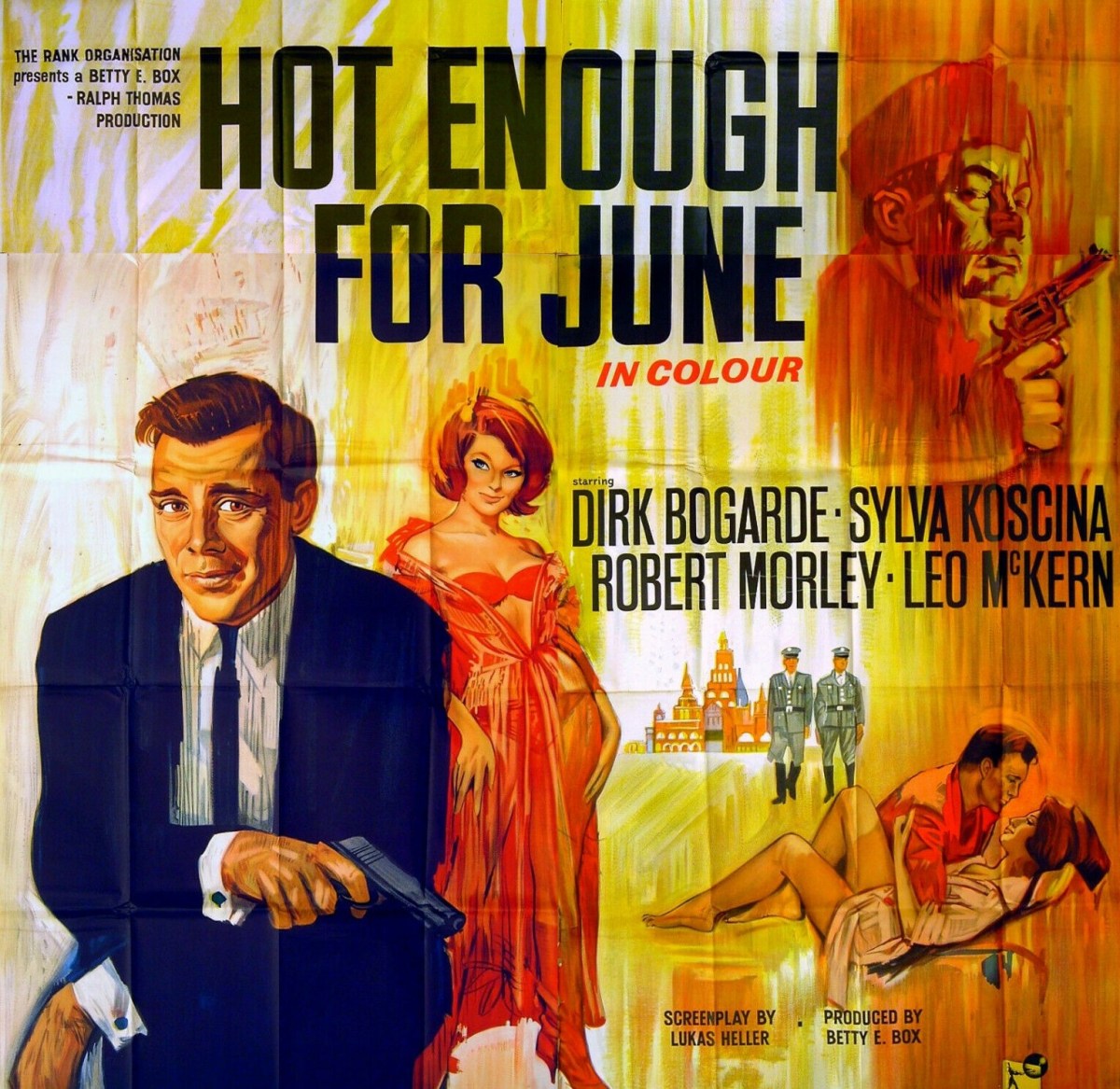

Confused? You will be. It’s clearly set up for James Robertson Justice to play two characters, a la Sinners (2025), his usual Sir Lancelot Spratt and his presumably identical brother, ship’s captain George Spratt. But Justice fell ill and the naval part was taken by Robert Morley, of similar bombastic ilk, but in diction more long-winded and fluffy and lacking the bite of the surgeon.

In the last two episodes I’d seen there had been an obnoxious salt-of-the-earth character who turned out to be surprisingly artistic. Here, we have to settle for the nouveau riche Pools-winner (a gambling game of the era) who is channeling his inner Sidney James, all leer and not much else. And if you want proof that it’s never a good idea to hire a television personality merely because he has a large following, look no further than Simon Dee.

Several notions will not endear themselves to the contemporary audience – the cross-dressing, the cliché gays, and the Englishman in brownface playing an Indian. That’s not to mention the pratfalls and endless falling into swimming pools.

There’s even less of a plot than in the last outing. Dr Burke (Leslie Philips) accidentally stows away on a cruise ship after pursuing model girlfriend Ophelia (Angela Scoular) who’s working there. He also comes up against actor Basil Beauchamp (Simon Dee), an old school bete noire, who plays a doctor in a television soap.

Dr Burke is hounded by the ship’s Master-at-Arms (Freddie Jones) so occasionally it lurches into farce. And there’s any number of sexy debutantes either desperate to climb into bed with the TV star or hook the gambler.

If it had settled on one tone – slapstick, sex comedy or farce – it might well have worked even in the face of the poor script. Cor blimey, there’s even some fleeting nudity from Ophelia and Leslie Philips and a striptease that’s way out of place for what was originally a much gentler comedy than the Carry Ons. In terms of style it’s all over the place and not a single member of the cast is appealing enough to rescue it.

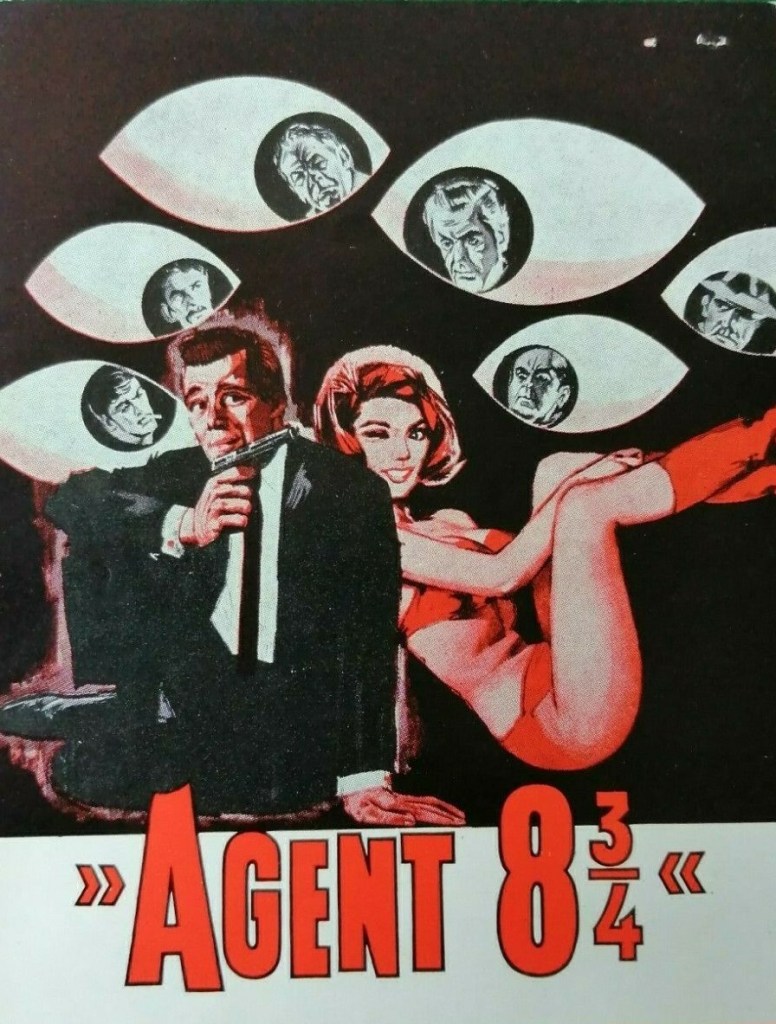

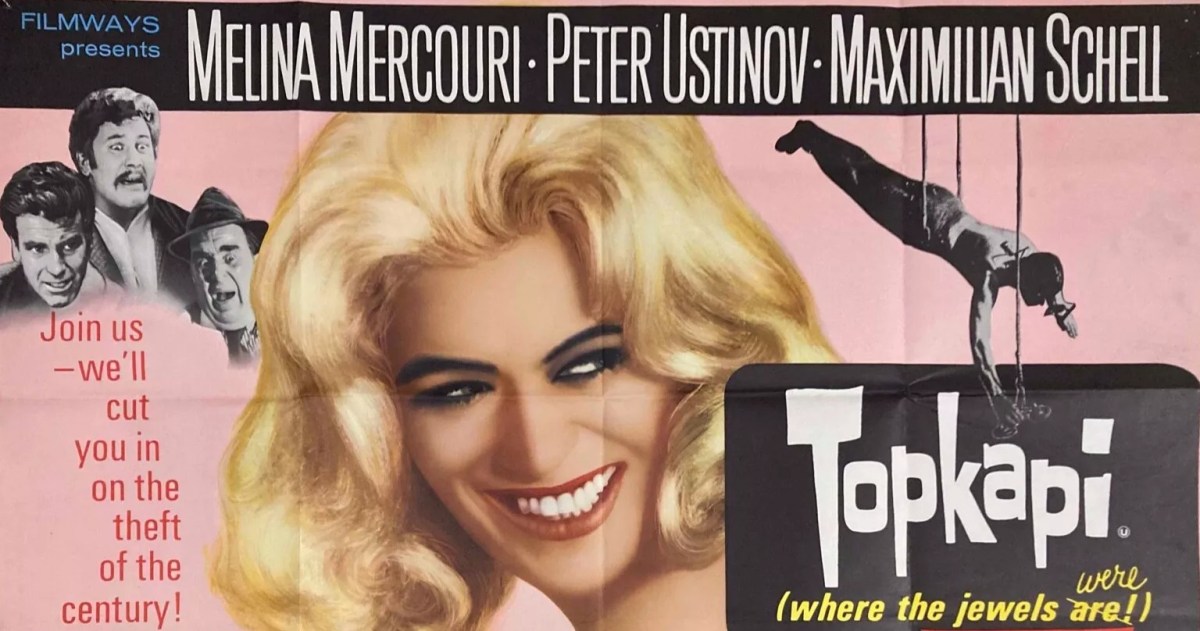

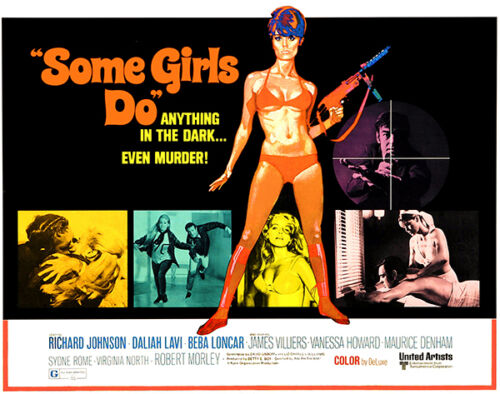

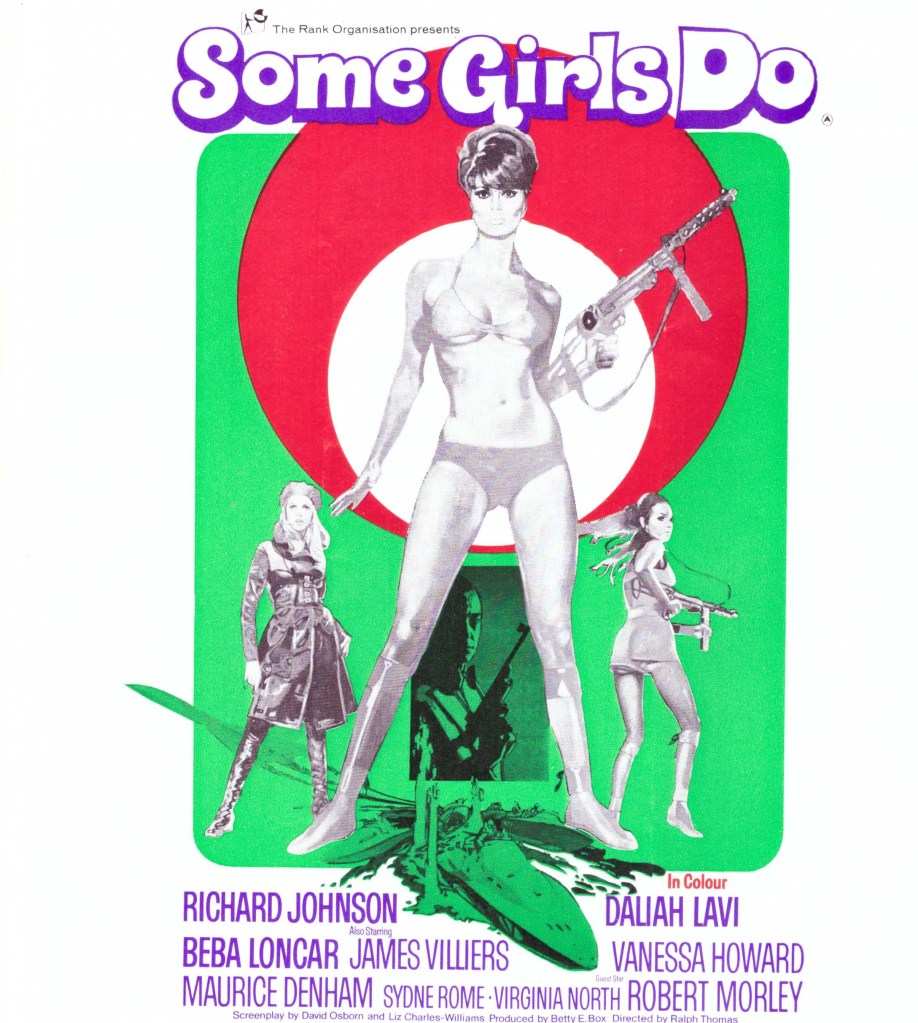

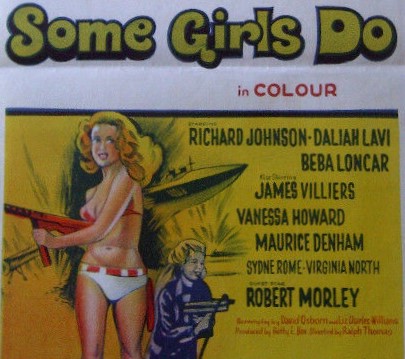

Had Leslie Philips been in traditional “ding-dong” comfort zone it might have passed muster but here he’s just the butt of all the jokes without generating an ounce of sympathy. Robert Morley (Some Girls Do, 1969) isn’t a patch on James Robertson Justice. Angela Scoular (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, 1969) seems off-key, Freddie Jones (Otley, 1969) as if he’s in a different picture while the constantly leering Harry Secombe (Oliver! 1968) belongs in a Carry On. Graham Stark (The Picasso Summer, 1969) is deplorable as the Indian waiter Satterjee.

The only person to rise above their station is Joan Sims (Doctor in Clover, 1966) who makes a cameo appearance as a Russian nurse. In bit parts you might spot Yutte Stensgaard (Zeta One, 1969) and Janet Mahoney in her debut.

Directed as usual by Ralph Thomas. Script by Jack Davies based on a Richard Gordon bestseller.

After this, the series was reimagined for television and returned to its gentle comedy roots.

For completists only – and even then…