J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone, 1961) saw a much-needed boost to a drifting career vanish when he ducked out of this project – he had spent considerable time developing the project – in favor of Mackenna’s Gold (1969). Blake Edwards, first director attached, probably also lamented losing out. This was to have been Edwards last outside film before committing exclusively to Mirisch.

Producer Arthur P. Jacobs, who had bought the rights to Pierre Boulle’s Monkey Planet in 1963, could hardly believe his luck after the calamitous Doctor Dolittle (1967). Unusually, the two films were not cross-collaterized, a standard studio device whereby the losses on one film were played against the profits in the other, which would have almost certainly resulted in no profit payments to Jacobs.

And you could probably say the same for eventual director Franklin J. Schaffner, relegated to television and movie stiffs like The Double Man (1967) after the failure of big-budget historical drama The War Lord (1965) and his abortive attempt to film the Travis McGee novels of John D. MacDonald, whose total sales exceeded 14 million. He wasn’t involved in Darker than Amber (1970), the first McGee title to be filmed. Heston, who Schaffner had directed in The War Lord, pushed for his involvement.

Charlton Heston was also in dire need of career resuscitation, his past five movies – Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee (1965), The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), The War Lord (1965), Khartoum (1966) and realistic western Will Penny (1967) – had all tanked. “In my view,” he opined, “I haven’t made a commercial film since Ben-Hur,” clearly ignoring the success of El id (1961).

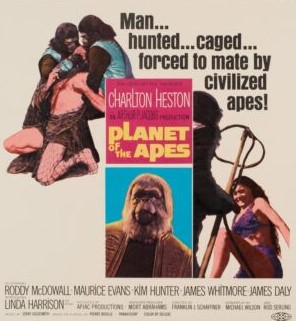

And once it became a success Warner Brothers regretted letting it go. The studio had been involved in the project when Blake Edwards was to direct. The movie was cancelled due to cost – it was budgeted then at $3-$3.5 million – and script and production problems. The studio might also have shied away after learning of the booming budget and lengthening schedule for MGM’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Twentieth Century Fox ended up forking out $5.8 million to turn the project into reality.

As was often the norm in Twentieth Century Fox pictures, studio head honcho Darryl F. Zanuck found a part for his mistress, in this case Linda Harrison as Nova, the mute love interest. She was a graduate of the studio’s program of investment in young talent. Others included Jacqueline Bissett (The Detective, 1968) and Edy Williams (The Secret Life of An American Wife, 1968). Had Raquel Welch (One Million Years B.C, 1966) considered the opportunity to don a fur bikini again, it is doubtful Harrison would have won the role. But she turned it down as did Ursula Andress (The Southern Star, 1969). Angelique Pettyjohn (Heaven with a Gun, 1969) was auditioned

Former child star Roddy McDowall (Lassie Come Home, 1943), Kim Hunter (A Streetcar Names Desire, 1951) and Maurice Evans (The War Lord) fleshed out the ape contingent. Ingrid Bergman (The Visit, 1964), also in much need of a career uplift, turned down the role of Zira. Other stars in the frame for roles included Yul Brynner, Alec Guinness and Laurence Olivier. Edward G. Robinson should have played Zaius, but couldn’t manage with the make-up.

Source material was Monkey Planet by Pierre Boulle, author of Bridge on the River Kwai. Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling took a year and a reported 30 drafts to turn in a viable screenplay and the former blacklisted Michael Wilson, whose name had been removed from the credits of Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962), added the polish. Wilson had won an Oscar for A Place in the Sun (1951) and another one for Friendly Persuasion (1956) although that was actually awarded to Jessamyn West since Wilson’s involvement was kept secret. If he had not been blacklisted, he would have been in the unusual position of having won four screenplay Oscars, although in the end the others were retrospectively awarded.

If you were looking for a sci-fi picture with dramatic heft, decent action, mysterious outcome and an examination of the human condition this was a more straightforward bet than 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). While Fox reckoned its previous sci-fi venture Fantastic Voyage (1966) had worked out well, it had reservations about the cost of Planet of the Apes and the possibility of making an ape setting believable. In this case the special effects’ conundrum was make-up for the apes. If they just looked like humans wearing monkey suits the movie would not fly. Fox spent $5,000 on a test with Heston in a scene with two apes before it greenlit the movie.

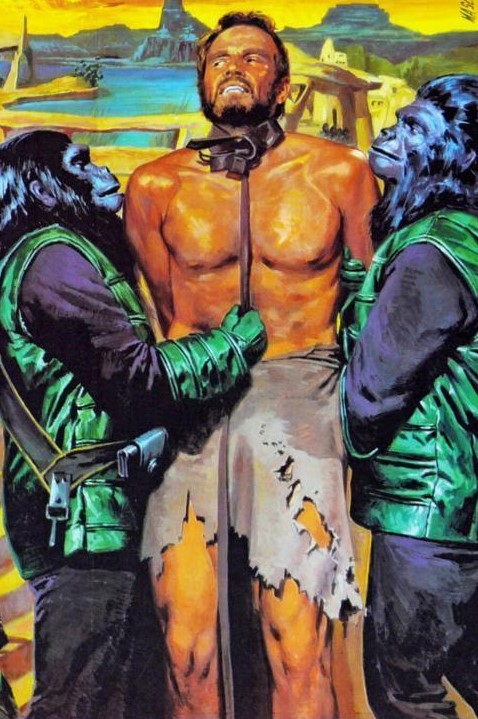

Faces that could not express emotion and were as stiff as a botox overdose would invite audience ridicule. In the end the studio spent a reported million dollars on pioneering ape renditions by John Chambers, who previously been a surgical technician repairing the faces of wounded soldiers. He had a team of 78 make-up artists There were almost as many scripts as crew and the changes wrought as the picture moved closer to being greenlit were to switch from a futuristic setting to a primeval one (which, incidentally, saved on costs), covering up the breasts of the female prisoners and inventing the stunning ending.

There were three possible endings, the one shot being that favored by the star.. Heston’s hoarse voice was not in the script, but an incidental by-product of him catching the flu. Apart from studio sets, the movie was filmed in blistering heat in Arizona. The rocket ship crashed into Lake Powell in Utah, ape city – modeled on the work of celebrated Spanish architect Gaudi – was constructed in Malibu Creek State Park, and the final scene was filmed on Zuma Beach in Malibu.

Unlike Fantastic Voyage which told audiences what the mission was, but in keeping with 2001: A Space Odyssey, Planet of the Apes opens with mystery. Like Rosemary’s Baby, the movie is viewed through the eyes of an innocent, one who cannot quite cotton on to his fall down the evolutionary food chain. Albeit more hirsute and muscular than Mia Farrow, nonetheless the casting of Heston dupes the audience into thinking he is somehow going to win, rather than just escape. He is an experiment who has wandered into the wrong planet. But there are few films that can top that shock ending. And the movie more than fulfills the “social comment,” on which Heston was very keen, contained in the Boulle novel.

SOURCES: Russo, Joe, Landsman, Larry, and Gross, Edward, Planet of the Apes Revisited, The Behind the Scenes Story of the Classic Science Fiction Saga (New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St Martin Griffin, 2001); Hannan, The Making of The Guns of Navarone, 187. “Warners Ape World,” Variety, March 18, 1964, 4; “High Costs Impress Capital,” Variety, March 23, 1964, 3; “Planet of Apes Off for Present,” Variety, March 10, 1965. “Michael Wilson Under His Own Name For A.P. Jacobs,” Variety, December 14, 1966, 7. “MacDonald Novels Cue Major Pictures Corp.,” Variety, May 17, 1967, 5; Austen, David, “It’s All A Matter Of Size,” Films and Filming, April 1968, 5; “Fox’s Talent School,” Variety, June 26, 1968, 13; Film Locations for Planet of the Apes,” www.film-locations.com.

I have to confess this Behind the Scenes article would have been better if I had not loaned out – and never got it back – my copy of The Making of Planet of the Apes by JW Rinzler which was published five years ago.