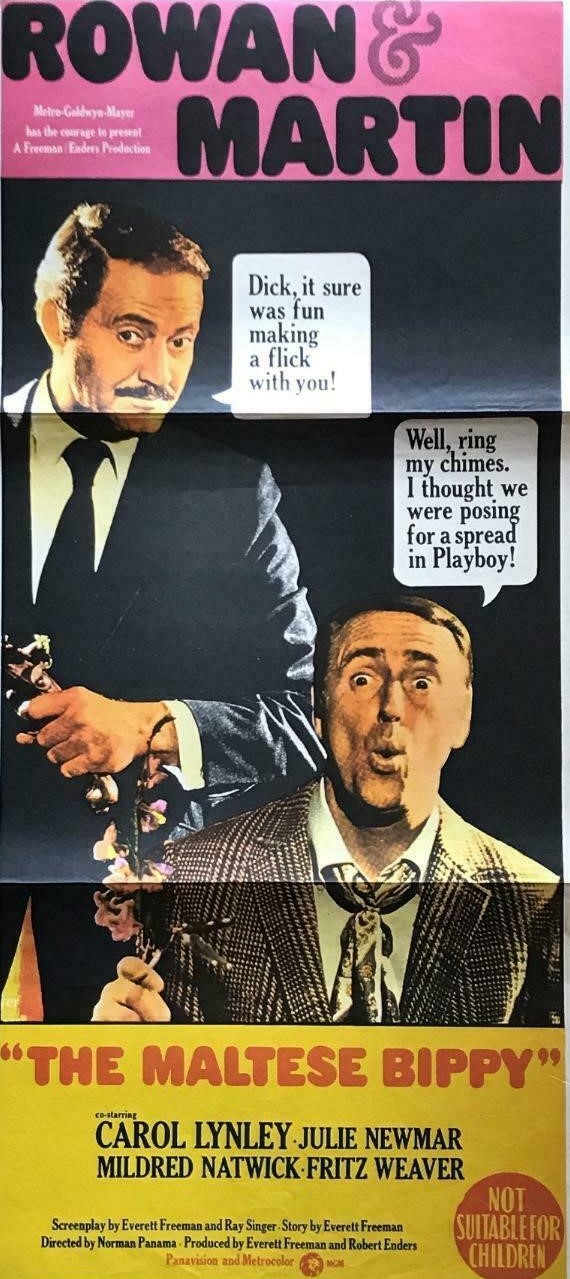

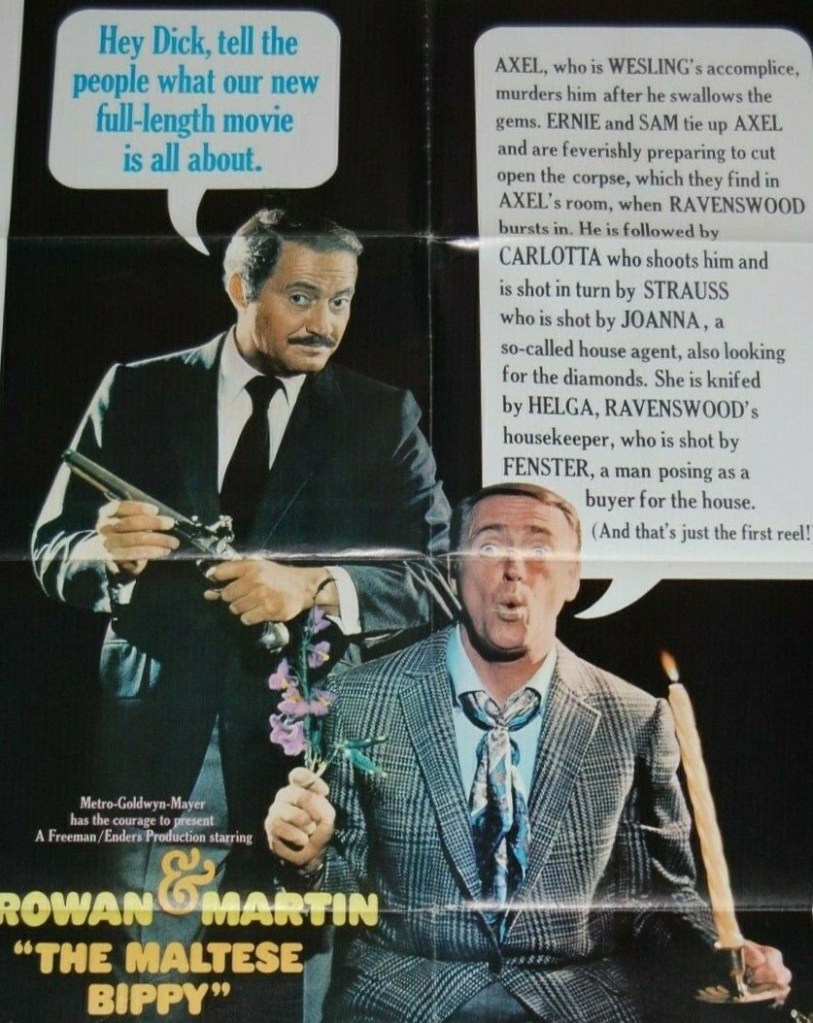

The start is promising. Three decent laughs in the first three scenes, all jests at the expense of Hollywood. But when the movie settles down to a werewolf spoof, there’s a nary a chuckle to be found. It was rare in the 1960s for television shows to be given a big-screen outing, but it did occasionally happen. This came two years into the six-year run of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In television show, an innovative mixture of gags, punchlines and sketches stitched together in random fashion. A huge hit in the U.S., it was considered a slam dunk to turn it into a movie. Perhaps if they had stuck to the same format it might have worked.

Sam Smith (Dan Rowan) and Ernest Grey (Dick Martin) are down-on-their-luck soft-porn movie makers living in a mansion on the edge of a cemetery. After suffering a bite on the neck, Dick turns into a werewolf. You can see the comic possibilities, I’m sure. Either Rowan and Martin failed to find them or lacked the expertise to turn the material into laughs. Sure, there’s a creepy family, the Ravenswoods, next door who could be auditioning for The Munsters but that goes nowhere except the obvious and certainly not in the direction of laughs.

A few good actresses – Carol Lynley (Danger Route, 1967), Julie Newmar (Mackenna’s Gold, 1969) and Mildred Natwick (Barefoot in the Park, 1967) – were snookered into this alongside Fritz Weaver (To Trap a Spy, 1964) without hope of redemption. It was almost as though the picture was conceived as a piece of merchandising that Rowan and Martin just had to put their names to and not do much else.

It was strange it was so awful because director Norman Panama had a track record in comedy. Among other pictures he had made The Court Jester (1955) starring Danny Kaye – “the vessel with the pestle” – displayed an abundance of great comic timing and in some respects was a spoof of the historical genre. He had also directed Bing Crosby and Bob Hope in The Road to Hong Kong (1962) so you would expect him to be familiar with the workings of screen comedic partnerships.

The laughs were meant to be supplied by Everett Freeman (The Glass Bottom Boat, 1966) and Ray Singer, a specialist in television sitcom and creator of Here’s Lucy (1968-1974). But either they couldn’t come up with sufficient gags or Rowan and Martin’s delivery was out of key with the lines. Or something.

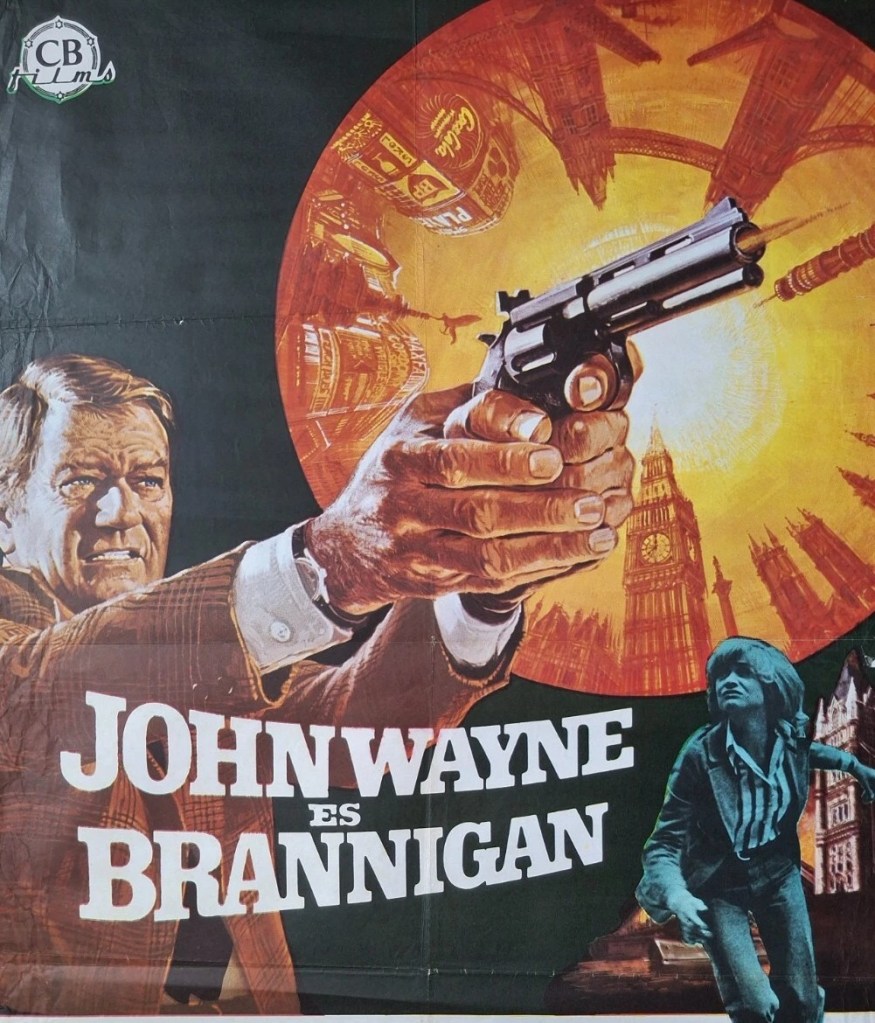

Maybe nostalgia was what was missing from my viewing of the picture. I don’t recall holding any particular affection for the television show, though I was aware it provided a star-making platform for performers like Goldie Hawn (Cactus Flower, 1969), Judy Carne (All the Right Noises, 1970) and Lily Tomlin (Nine to Five, 1980) and that John Wayne put in a guest appearance.

But don’t take my word for it. Variety called the picture “as zany and fast a funfest as has come down the pike in years” and a “ cinch for heavy box office reception.” Mainstream critics were less kind, four out of the most prominent five giving unfavorable reviews. Even though the stars made the cover of Life magazine and the film received a seven-page spread inside, the movie barely made a ripple with audiences, a total of just $22,000 garnered in its opening week in two cinemas in New York with a total capacity of over 2,000 seats. British kids film Ring of Bright Water made more at a 360-seater.

The expected audience did not materialize, either from poor word-of-mouth or because customers resisted paying for something they could get for free every week on the small screen. So poorly did it perform that its initial run was truncated and a few weeks later when it went wide in a Showcase opening in New York MGM stuck on a reissue of Grand Prix (1966) as the support. Variety estimated it barely took $1 million in rentals (the amount returned to studios once cinemas take their share of the box office). Final proof of its unpopularity was being sold to television a couple of months after its debut.