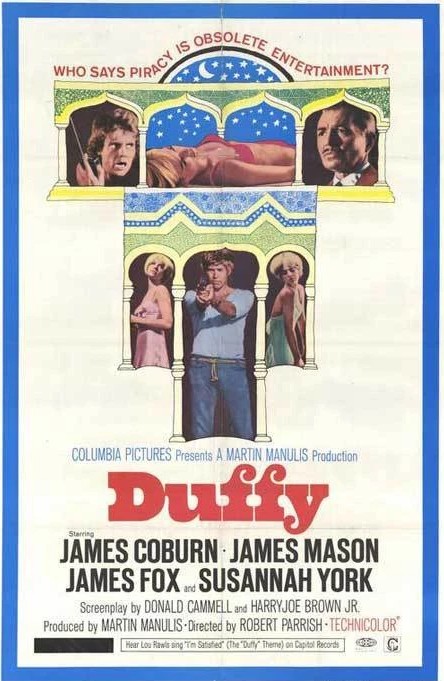

Star James Coburn wasn’t keen on the title. Had it been made today it would have been a contender for the sobriquet of The Nepo Heist. I’m sure many heirs would quite like a large chunk of their inheritance put in their hands long before it was handed over after the death of the father/mother. Luckily, this isn’t about blatant greed. It’s presented as more of a game, a duo of half-brothers, same father/different mother, trying to put one over their arrogant father.

Millionaire businessman J.C. Calvert (James Mason) is as keen on keeping the kids in their place, constantly deriding as incompetent Antony (John Alderton) – an accurate assessment it has to be said – and more than willing to challenge Stefane (James Fox) to any game of skill, even darts, especially if it involves money.

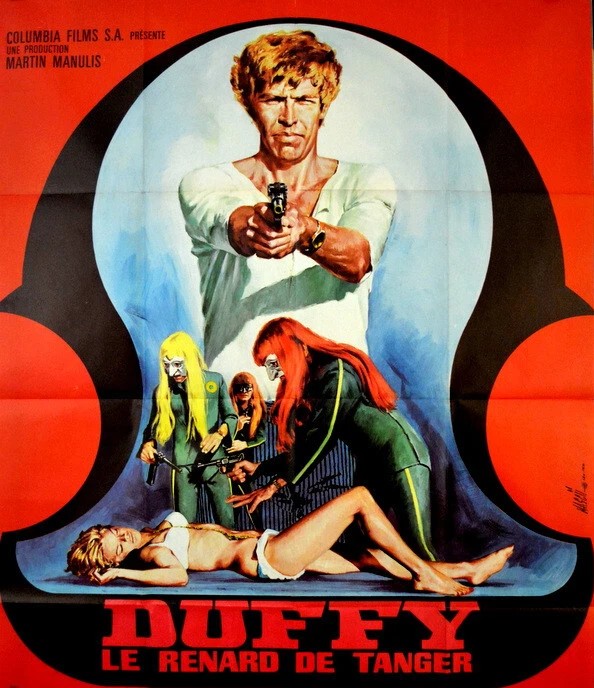

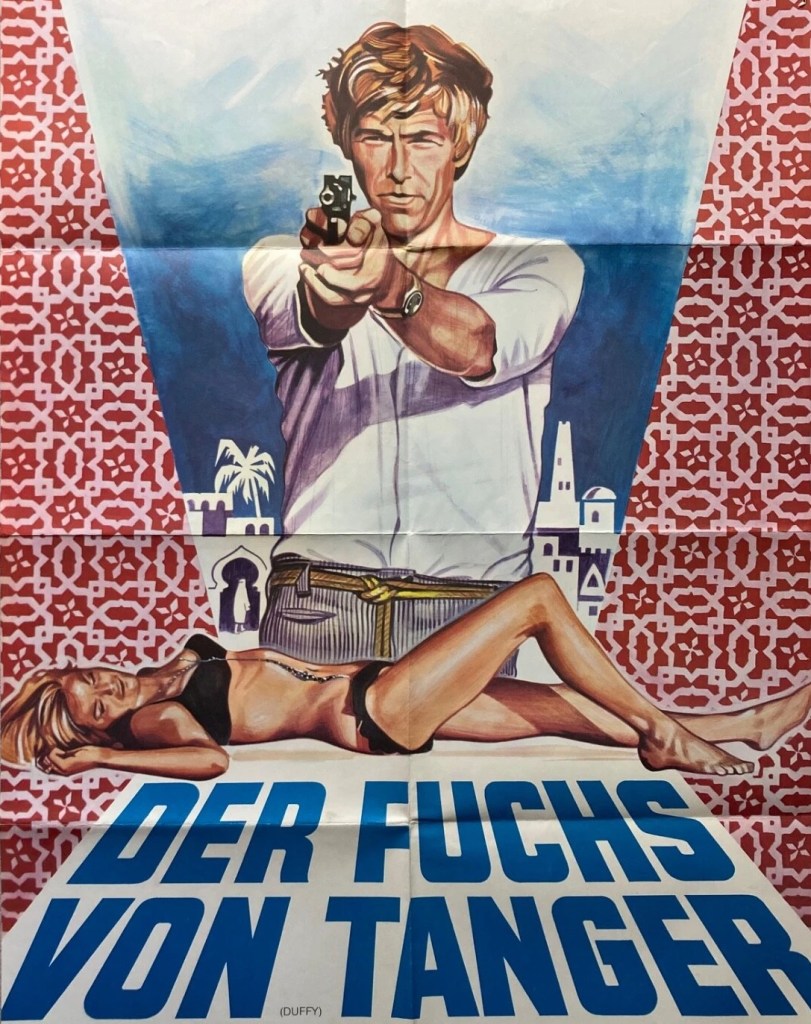

The sons set out to steal £1 million ($3 million) from a shipment of cash their father is transporting aboard the passenger ship Osiris to Naples. To that end they recruit hippy smuggler Duffy (James Coburn). Stefane’s girlfriend Segolene (Susannah York) might have been included as a makeweight except she takes a fancy to Duffy. Given that betrayal is a standard trope of any heist, you are kept wondering if she is, in fact, no matter how she protests her independence, a plant.

It takes quite a while for the plot to gather any steam what with dilly-dallying around Tangier and making considerable adjustments to a yacht. No time is spent either in the planning of the crime, the action just unfolds. The theft itself requires little of the unique set of skills that most thieves possess, nothing more than going on board the Osiris in disguise, both Stefane and Segolene decked out in religious garments, and putting on masks for their incursion into the room containing the safe. The only moment of real tension comes in having to extract the code to the safe.

The escape is better thought-out. The cash is chucked overboard in buoyant bags, connected to Duffy by means of a fisherman’s line which, when reaching the safety of their yacht, transformed for the time being into a fishing boat, Duffy reels in. A helicopter magically appears from the hold and they blow up the yacht before escaping, stashing the loot in 30ft of water in a cove near Tangier.

Assuming J.C. would be able to claim on his insurance then no great harm would be done to the family coffers, and the sons, as well as filling their pockets, would have the pleasure of making a fool of their old man. As you might expect, there’s double crossing still to come. And it’s a gem of a twist. Calvert has been in on the crime from the outset, thanks to the connivance of Segolene who turns out to be his girlfriend.

However, that scam is undone in another twist and it’s Duffy who comes out trumps, though far short of a millionaire.

Relies more than most crime pictures on the charm of the three main characters, with Antony there for nuisance value. However, the will-she-won’t-she games Segolene plays with Duffy and Stefane would have had more impact if Stefane had not been so nonchalant about their romance, and if she had not been so strident as regards her independence and unwillingness to become attached to any man.

That said, she turns out to be the cleverest of the lot, stringing along the two younger men while making a better play for the older one. But there’s something missing in the construction of the picture, so her triumph seems to come out of left field, almost a twist for the sake of it.

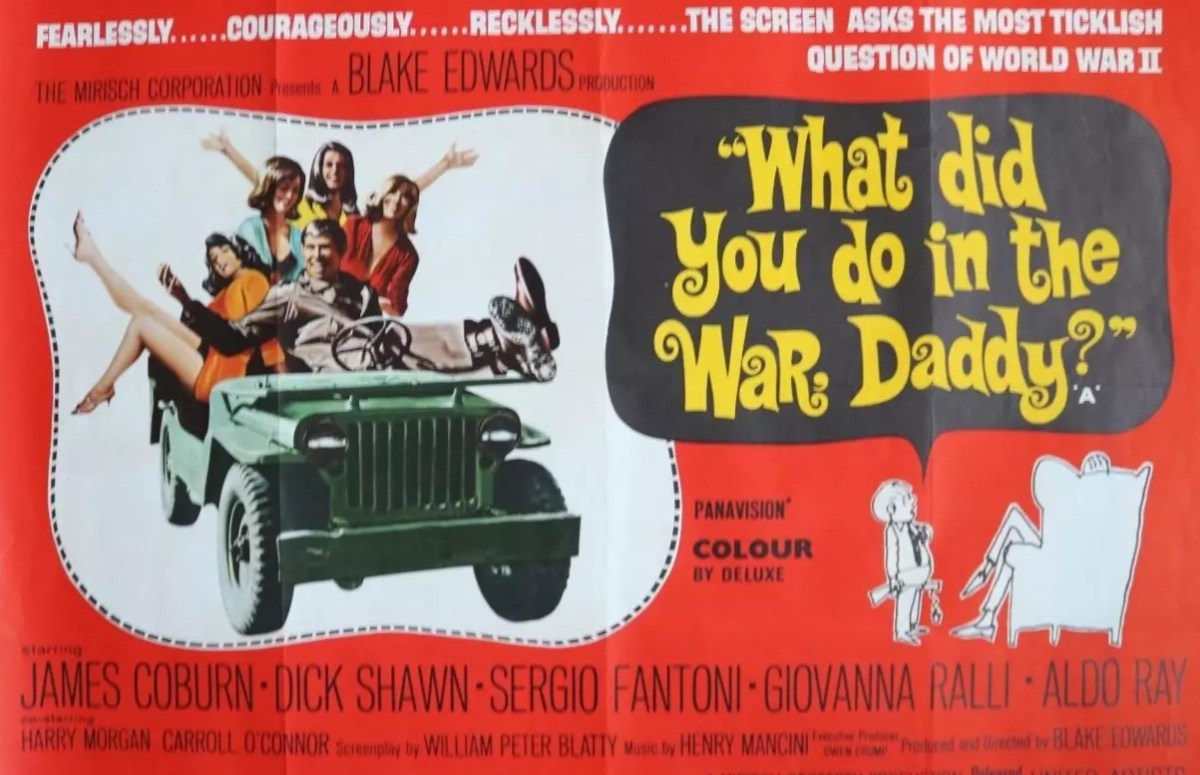

James Coburn (What Did You Do In The War, Daddy?, 1966) gives his screen persona an almighty about-turn, and although he appears useful with a pistol, he comes across more as a free-living hippy of the period, with a penchant for erotic pop art, though he has little regard for ecology, literally littering the planet, chucking wrappers and bottles everywhere.

James Fox (King Rat, 1965) has a whale of a time as an insouciant aristocrat, a character trait he clearly inherits from James Mason (Age of Consent, 1969) as his father while Susannah York (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965) swans around in cool attire all the more to make herself appear nothing more than a mild distraction rather than a criminal genius.

Leisurely directed by Robert Parrish (Journey to the Far Side of the Sun, 1969) from a screenplay by Donald Cammell (Performance, 1971) and Pierre de la Salle and Harry Joe Brown Jr.

Very slight.