One description of this film’s prequel The Nightcomers (1972) was that, even with the overt sex and violence, it was an arthouse picture masquerading as a horror movie. And obviously absent the sex and violence that’s how I feel about this one. I’m of the old-fashioned school when it comes to horror – once in a while I expect to jump. The biggest problem here is that fear is telegraphed in the face of governess Miss Giddens (Deborah Kerr). Instead of the audience being allowed to register terror, all the tension is sapped away by one look of her terrified face.

Atmospheric? Yes! Scary? No.

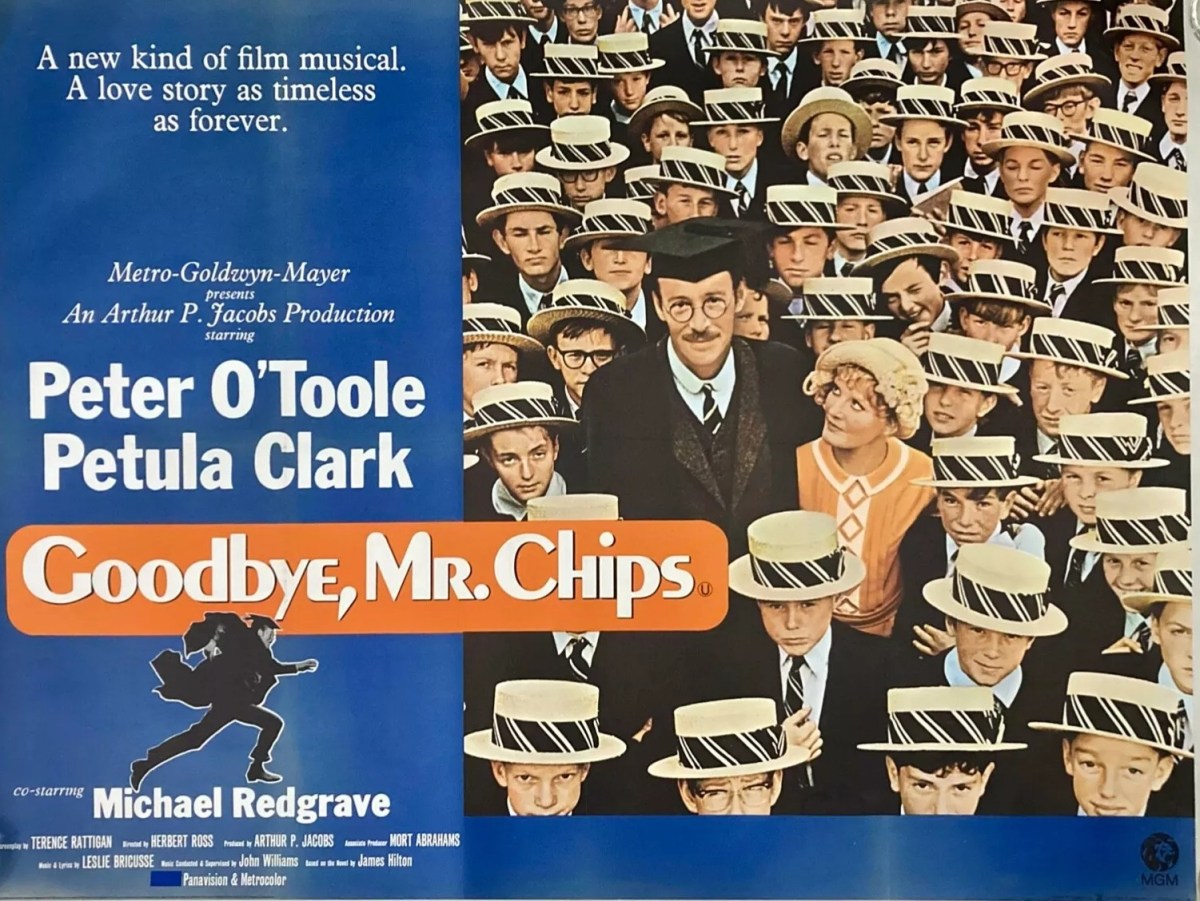

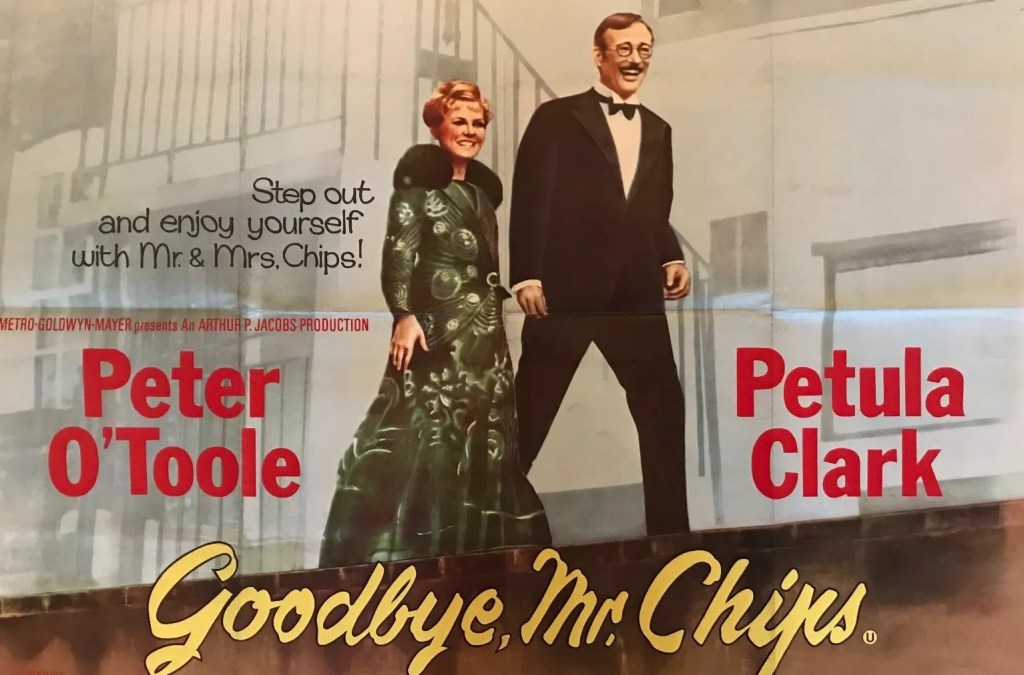

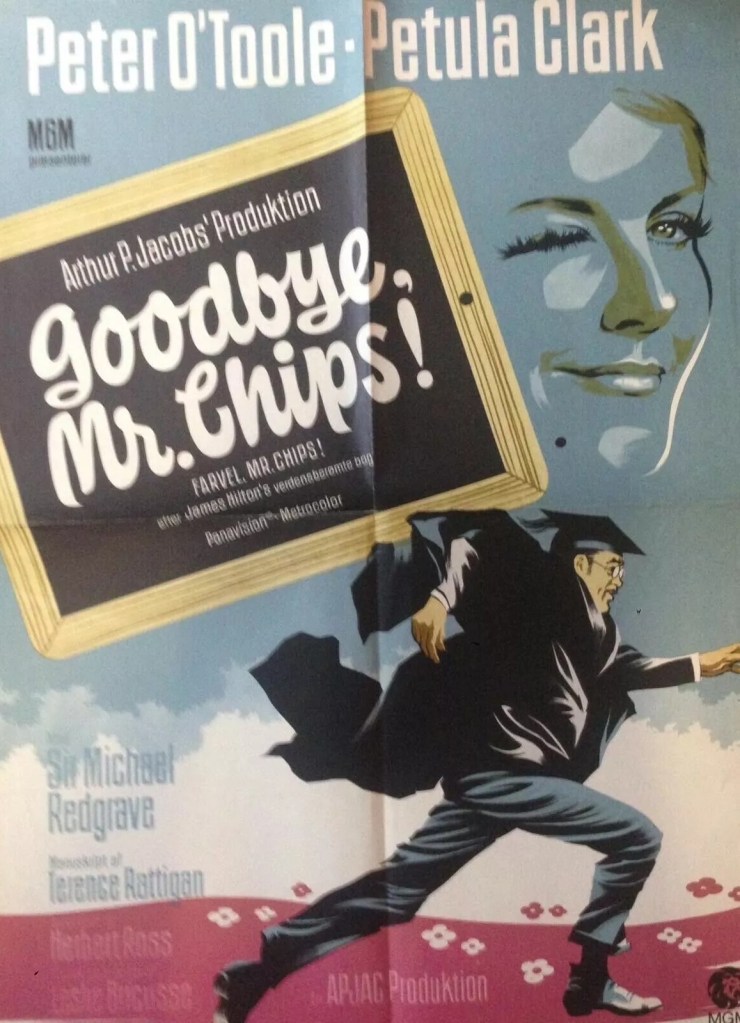

Certainly, the set-up is likely to spark the darkest imaginations. Orphans Miles (Martin Stephens) and Flora (Pamela Franklin) are abandoned by their uncle (Michael Redgrave) who wants to spent his time enjoying himself in faraway London without having to bother about the care of the minors. The governesses he installs are given carte blanche to deal with any situation that arises – as long as they don’t concern him with it. And he’s so disinterested in the children’s welfare that he hires a completely inexperienced governess in Miss Giddens despite the fact that the previous occupant of the post, Miss Jessel, had died in mysterious circumstances and a little digging would have revealed that she lived a hellish life under the thumb of valet Quint.

The kids appear somewhat telepathetic or telekinetic – Flora knows Miles is coming home before Miss Giddens does, Miles knows when the governess is standing outside his door. They’re maybe a too bit self-indulgent – Flora enjoys watching a spider munch on a butterfly and isn’t above finding out if her pet tortoise can swim, while Miles has Miss Giddens in a neck stranglehold.

But it’s unlikely the children are summoning ghosts – Quint appears to Miss Giddens at the top of a tower and again peering in through a window, Miss Jessel turns up, too, and I lost count of the number of disembodied voices. The ghosts it turns out have taken possession of the children in order to continue their relationship.

And while this is all very clever it does not chill you to the bone. The children are not as cute as they need to be to make this work. You get the impression, given half the chance, they would happily turn into little savages and experiment with all manner of cruelty. And that would occur whether there was the likes of Quint around to lead them astray because the adults in their lives are so selfish and set the wrong kinds of standards. But with the focus perennially on the trembling Miss Giddens, there’s little chance of getting inside the heads of the children.

Since jump scares are not in director Jack Clayton’s cinematic vocabulary, the best scenes are not visual, but verbal, housekeeper Mrs Grose (Meg Jenkins) filling the governess in on the unequal relationship between Quint and Miss Jessel, Flora imagining rooms getting bigger in the darkness (effectively more dark), Miles seeing a hand at the bottom of the lake.

There’s certainly an elegiac tone and the camera clearly sets out to destabilise the audience but that’s just so obvious it seems more an arthouse ploy than a horror schematic.

This was start of Deborah Kerr (Prudence and the Pill,1968) playing psychologically distorted characters. Over the previous decade she had revelled in a screen persona that saw her playing the female lead (sometimes the top-billed star) opposite the biggest male marquee names of the era – Burt Lancaster (twice), Cary Grant (twice), Yul Brynner (twice), Gregory Peck, William Holden, Robert Mitchum (three times), David Niven (twice), Gary Cooper. Now she turned fragile and that screen persona, introduced here, would see her through the next decade.

So she’s both very good and very bad here. Her character facially registers her inner thoughts but those too often get in the way of the audience. I found the kids more limited in their roles, not through acting inexperience, but through narrative restriction.

Jack Clayton (Dark of the Sun, 1968) directs from a screenplay by Truman Capote (In Cold Blood, 1967) and William Archibald (I Confess, 1953) from the celebrated Henry James story.

A bit too artificial for my taste. Probably heresy to admit it but I preferred the prequel.