Just about scrapes by, small thanks to Paul Newman’s atrocious Texan accent, Joanne Woodward’s frightful blonde wig – more Lady Penelope than classy Parisian – and Maurice Chevalier serenading a horde of drunken women. Maurice Chevalier? Well, of course this is Paris and Chevalier always sings regardless of being peripheral to the story.

Suffers, too, from being a smart-ass picture, in the vain hope of hitting the satirical bullseye taking swipes at everything in sight, from women barging into a sale to haute couture, airline stewardesses, journalism and even Paris. And there’s a string of fantasy sequences that might (or might not) have worked at the time but fail to gell now. Takes forever for the principals to even be brought close enough together to envisage romance and it doesn’t help that that supposedly most eagle-eyed of creatures, the reporter, can’t see through a simple disguise.

Tomboy Sam Blake (Joanne Woodward) is a pirate. Not the swashbuckling kind, leaping through the rigging, which would be worth seeing I’m sure, but the industrial kind, stealing the designs of better designers for a New York department store.

Steve Sherman (Paul Newman) is piratical, stealing other people’s wives. When his latest conquest turns out to be married to his boss, he is shifted off to Paris as – punishment? Yep, you can see the awry thinking behind this one.

Meanwhile, Sam and a gang from her store, boss Joe (George Tobias) and colleague Lena (Thelma Ritter), are off to Paris on a spying expedition to the annual fashion shows. Lena has her eyes on romance with the boss but is beaten to that prize by the glamorous Felicienne (Eva Gabor). Sam isn’t interested in romance. She’s a career woman, or in the parlance of the day, a “semi-virgin” (though I suspect that description was a screenwriter’s invention). Neither is Steve, for that matter, at least not of the long-lasting kind, he’s happily tearing around with a woman on each arm, enjoying the more nefarious sights of the French capital while Sam is knee deep in work.

After Sam gets a makeover, complete with long cigarette-holder Lady Penelope style, resulting in the bouffant hair style and is sitting in a café, she is approached by Steve who, assuming she is a high-class courtesan, attempts to interview her for the article he hopes will save his job. They’ve bumped into each other, she disdaining his obvious approaches, a couple of times but then she was rigged out in a short haircut and dark glasses. And this is such a complete transformation he doesn’t recognize her. And, in order to make this movie work, the audience has to play along.

As does Sam, keeping up the pretense of being a high-class hooker in order to get her revenge on the man she despises. The fictions she dishes up, of dalliances with powerful men, are published in his column and their success ensures he’s not fired. Felicienne is edged out of the way, revealed as previously a sex worker, so Lena can make her play for Joe.

Before that ploy can work, Steve sets up Sam with Joe who sees through the disguise. There’s a whole bundle of other unlikely shenanigans before we reach the compulsory happy ending.

Hollywood was fairly enamored with the sex worker or goodtime girl – Never on Sunday (1960), Butterfield 8 (1960), Irma La Douce (1963), for example, with the Oscars chipping in to show their support – and another (yes, this had been done before) comedic twist seemed to offer potential especially with two big stars going all risqué.

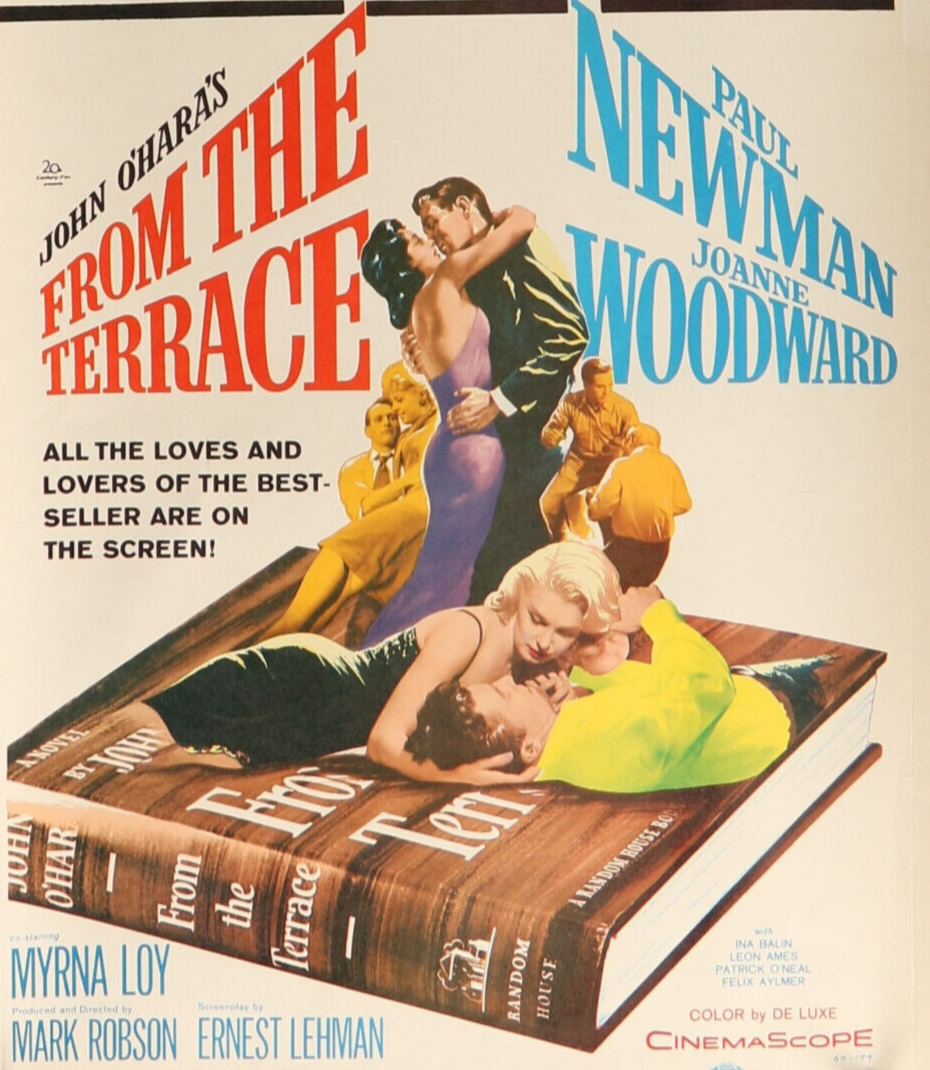

Paul Newman (The Prize, 1963) never quite worked out how to manage comedy until Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) where he maintained his usual persona and just delivered the lines rather than trying to wring laughs out of them. He also has a bad habit of trying to demonstrate character by fidgeting, so his face, eyes and hands are all over the place.

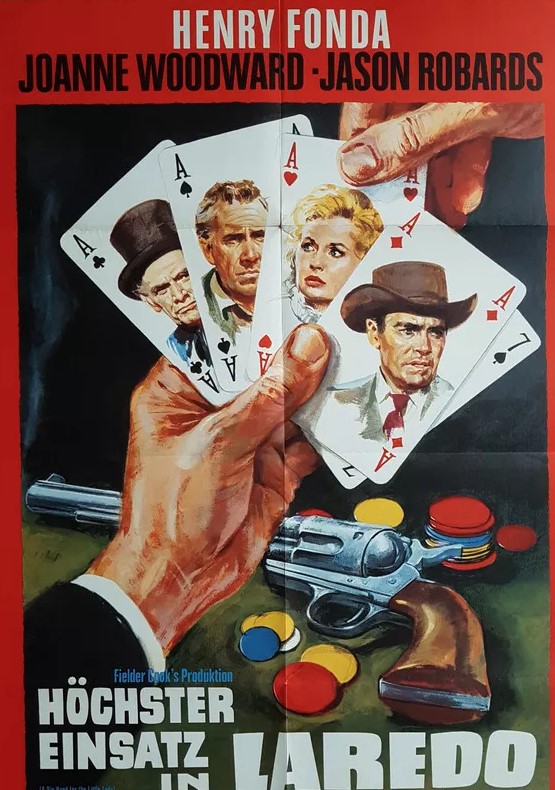

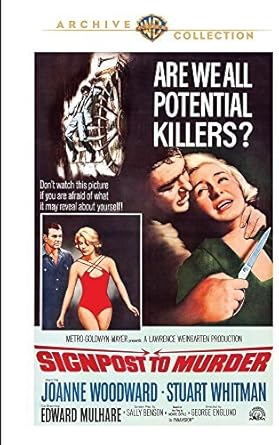

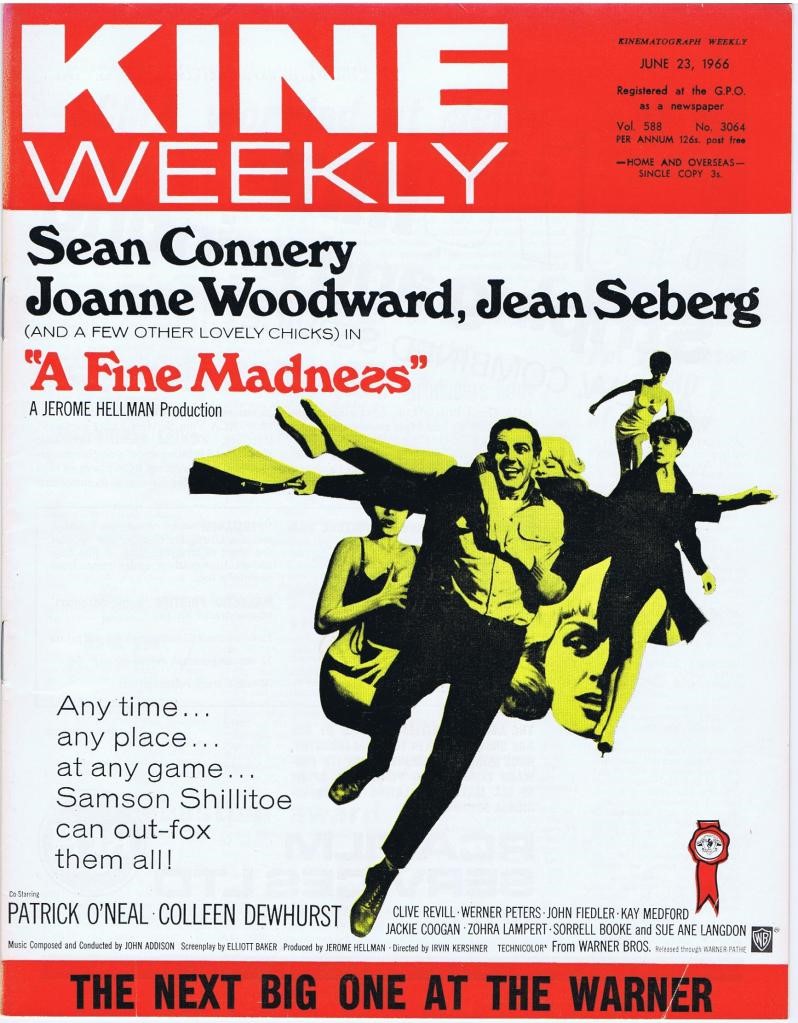

Joanne Woodward (A Big Hand for the Little Lady/ Big Deal in Dodge City, 1966) is better value initially but when she takes on the disguise there’s too much of the knowing wink. Six-time Oscar nominee Thelma Ritter (Boeing, Boeing, 1965) has a better idea of how to play comedy by just sticking to the knitting.

Writer-director Melville Shavelson (The Pigeon That Took Rome, 1962) just about makes it work and when it doesn’t throws in sufficient distraction.

Not the Newman-Woodward team’s finest hour.