Beautifully constructed, stylish, compelling narrative about passion, betrayal and the death of a dynasty. Just as The Godfather is not just about the Mafia, this is not just about fashion; rather, both fit into the niche of movies about family. In each, there are principled fathers and both weak and strong sons. While decisions are driven by character, ambition clogs the mind and ultimately it is the clear-sighted who win.

In a beautifully-played love story outsider Patrizia (Lady Gaga) manages to snag Gucci heir Maurizio (Adam Driver), her lowly status driving a wedge between him and ill patriarch Rodolfo (Jeremy Irons), who shares control of the company with his brother Aldo (Al Pacino). Almost a geek poster-boy, Maurizio nonetheless fits easily into her world. But when Aldo draws Maurizio into the family business, it triggers conspiracy and betrayal.

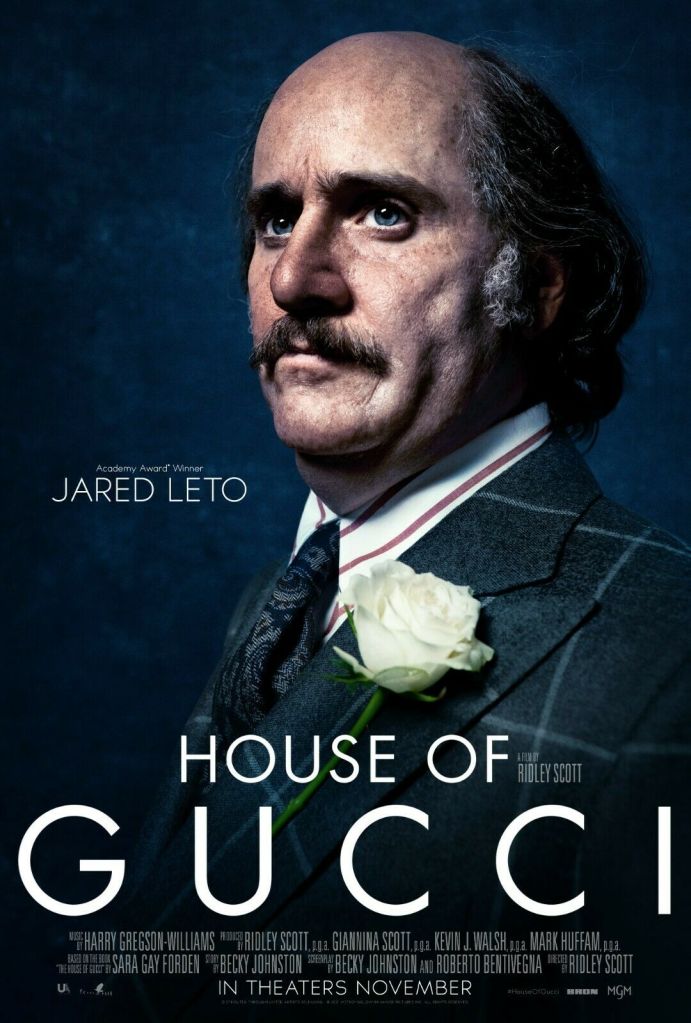

Aldo and Rodolfo are polar opposites, the former willing to dilute the brand in the race for profit, the latter seeing himself as the curator of a more sedate way of doing business. While Rodolfo pines for his dead wife in his palatial Italian sanctuary, Aldo has an eye for the ladies in New York. The weak link in the family chain is Aldo’s “idiot” son Paolo (Jared Leto) who considers himself a fashion genius. But, in reality, they are all weak, seduced by wealth and power, believing themselves untouchable despite wholesale fraud, business folly and self-delusion on a colossal scale.

The quest for power is ostensibly driven by Patrizia, but she proves no match for a flinty-eyed Maurizio. And for his all self-aggrandisement, Maurizio proves no match for the circling predators, his rampant self-indulgence a death wish in a boardroom.

Over-acting could have sent this picture off the rails but everyone is terrific and the soap-opera tag is unfair. In the best Shakespearian style, hubris accounts for tragedy. Few characters escape humiliation. Paulo may be a figure of fun, but his mortification at the hands of Rodolfo renders him extremely human. Aldo may exalt in his business skill but in the face of betrayal is destroyed. Patrizia receives a massive put-down by Maurizio in front of his high-class friends.

Lady Gaga, who demonstrates the onscreen radiance and incandescence of a latter-day Elizabeth Taylor, is superb as the woman whose prize is snatched away. Adam Driver puts in his best performance yet, so natural, and his scenes with Gaga are electrifying. Al Pacino encompasses a massive range, man in his pomp, loving father, and in the depth of agony at betrayal. Jared Leto is a revelation, and an early Oscar favourite, as the ridiculous and ridiculed son. Jeremy Irons and Jack Huston as the conniving lawyer are excellent

There are so many brilliantly-wrought scenes – seduction on a rowing boat, a rugby match that gets out of hand, a snake-pit of a boardroom, Aldo lavishing attention on his cows, Patrizia indulging a psychic (Salma Hayek), Maurizio leaping around a room for a Vogue photo shoot. A weighty look at the corruption of power but also a fabulously entertaining picture. Better known for visual tropes, here Scott displays his mastery of narrative as we sweep in and out of unbridled egos hell bent on triumph at any cost. And it is the best film about business since Wall St (1987).

When I first watched this, I was inclined to give it a four-star rating but after seeing it a second time on the big screen that appeared niggardly for a work of such awesome majesty. (Now that I’ve seen it a third time, the five-star ranking still stands). Just like American Gangster (2005) and Thelma and Louise (1992), when Scott moves outside his self-appointed sci-fi and historical treasure trove, he does so with effortless style. This just zipped along. I hardly noticed the time at all. Second time around, I just did not want it to finish, I was so immersed. I even found myself laughing at the same jokes and situations.

What a banner year for the 83-year-old British director. The Last Duel could have bookended this piece – wronged woman proved innocent compared to wronged woman found guilty. Given Scott is synonymous more with the historic than anything approaching the contemporary, I thought I would have preferred The Last Duel, but I now consider House of Gucci the greater film.