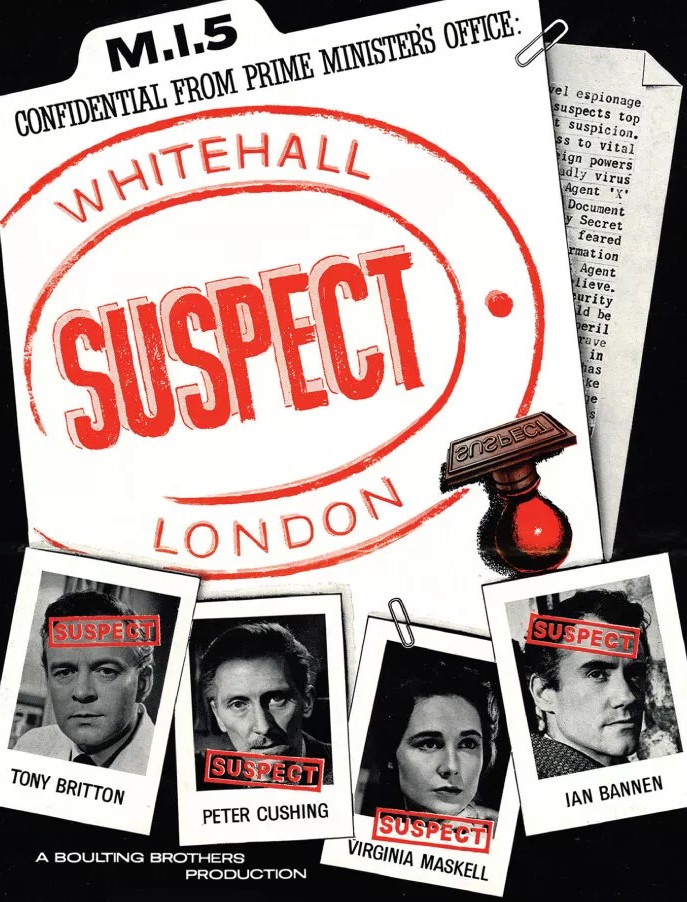

Marvellous long-forgotten character-driven espionage drama exploring the twin themes of guilt and duty. It would appear to be stolen by two supporting actors, Ian Bannen and Thorley Walters, but in fact both play roles that have significant bearing not only on the narrative but on our understanding of the most important characters. Not only do we have the main plot, but we also have two well-worked sub-plots, one concerning disability and the other of more sinister relevance – a 1984 Big Brother theme.

Basic tale concerns a laboratory that has discovered a bacteria that can cure plague. Hopes of a celebratory drink all-round and academic kudos on publishing his paper for top boffin Professor Sewell (Peter Cushing) are dashed when the Government in the shape of the pompous Sir George Gatling (Raymond Huntly) steps in, steals the discovery and makes the staff sign the Official Secrets Act.

While the revered professor takes it on the chin, colleague Bob Marriott (Tony Britton) is outraged so vocally in public that he attracts the attention of the shady Brown (Donald Pleasance) who suggests to the dupe that there is a way of getting the information out to the wider scientific community, especially to plague-ridden countries.

However, don’t let Sir George’s pomposity fool you. He doesn’t trust this bunch an inch and puts the Secret Service on their tail to assess “the risk” and we dip into the dark kind of web (not that kind of dark web) and the mundane business of deception and betrayal shortly to be explored by the likes of John Le Carre (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, published in 1963) and Len Deighton (The Ipcress File, published a year earlier).

Rather than this outfit being headed by a version of the prim George Smiley, Mr Prince (Thorley Waters) has a lot more in common with the unkempt Jackson Lamb of the Slow Horses series. His incompetence is an act to make visitors to his shambles of an office under-estimate him. But he’s got that Columbo knack of asking the most important question just when an interviewee thinks the interview is over.

Also in the background, coming more increasingly into the foreground, is an unusual love triangle between colleagues Bob and Lucy Byrne (Virginia Maskell), who kiss and hold hands in the cinema, and Lucy’s flatmate, the disabled war vet Alan Andrews (Ian Bannen). The fact that Lucy and Alan live together at a time when such a relationship was frowned upon and would be career death in certain circles and that they were once engaged to be married gives it an edge. That Alan has lost an arm and a hand so needs to be cared for – fed (as in food spooned into his mouth), washed (you can guess that aspect), cigarette lit and removed between puffs, dressed – suggests significant intimacy for an adult.

Obviously, she’s the kind of lass who couldn’t abandon him to the welfare system, and he’s the kind of man who broke off their engagement so she wouldn’t feel tied to him for the rest of her life. But he also hates what he’s become, his desperate reliance on her, what he’s lost, and that’s turned him into not just a bitter individual but a particularly cunning one, who has developed the trick of torpedoing any nascent romance. “You can’t compete,” he gloats to Bob, “because you can’t make her feel good.”

But when that doesn’t work, he befriends Bob and surreptitiously eggs him on to betray his country and in so doing, hopefully, kill off the romance.

Mr Prince is a delight. Accorded the best lines, he makes great use of them. When his subordinate Slater (Sam Kydd) abrasively brings Dr Shole (Kenneth Griffith) in for questioning, he reprimands him with the rather coy, “Oh, you haven’t been rough again.” To Dr Shole (Kenneth Griffith), the most susceptible of the professor’s acolytes, he warns, “Tell him (Sewell) not to be a fool or you’ll smack him on the backside.” Though Dr Shole has a superb retort, “We’re not exactly on those terms.”

Professor Sewell appears mostly on the back foot. While quietly seething at being denied his professional day in the sun, he accepts duty. Even so, he’s smart enough to outwit Prince when the traitor is caught.

The background of the wheels-within-wheels of Government, the silent overseeing of ordinary lives, the authorized level of spying, comes as something of a shock, since despite George Orwell’s best efforts Big Brother was seen as a clever fiction that could not occur in this most democratic and upright of countries where “fair play” was the rule. Visually, this is well done, we see eavesdroppers in mirrors in pubs and, as I said, Prince seems the least effective of operatives but with the kind of personality that you could easily have built a series around.

Disability from war was a constant of post-war British pictures, most often demonstrated by a character with a limp, as with general dogsbody Arthur (Spike Milligan) here. The Oscar-winning The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) was the most effective at dealing with the physical after-effects of the Second World War. But there, the worst-affected soldier, had prosthetic hands. Here, Alan does not, so the scenes of him being tended to by Lucy are emotionally more powerful.

She tends to his emotions, too, and will embrace him and kiss him on the mouth though he’s not dumb enough to read true romantic commitment into those demonstrations of affection. Clearly, there is emotional residue from their engagement, from which you guess she will ultimately be unable to entangle herself, unless he can find a more brutal way of helping her out of the dilemma.

The lab aspect is surprisingly well done. We don’t get any real information on the scientific breakthrough. Mostly, what we view is the grunt work, the laborious checking of thousands of samples for another experiment. At one point Bob thrusts his arm into a contraption packed with buzzing flies as if he was a competitor in I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here.

Ian Bannen (The Flight of the Phoenix, 1965) is the standout but character actor Thorley Waters (Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace, 1962) runs him close. Tony Britton (better known later for television comedy) has the least interesting role, but Virginia Maskell (Interlude, 1968) has too much to do without dialog to demonstrate her dilemma. Peter Cushing (The Skull, 1965) is solid as always and Spike Milligan provides light relief.

Joint direction by the Boulting Brothers (The Family Way, 1967), Roy and John. Screenplay by Nigel Balchin (Circle of Deception, 1960) based on his own novel.

Exceptionally solid stuff. I was very much taken by the unusual approach, the themes and the acting.

Worth a look.