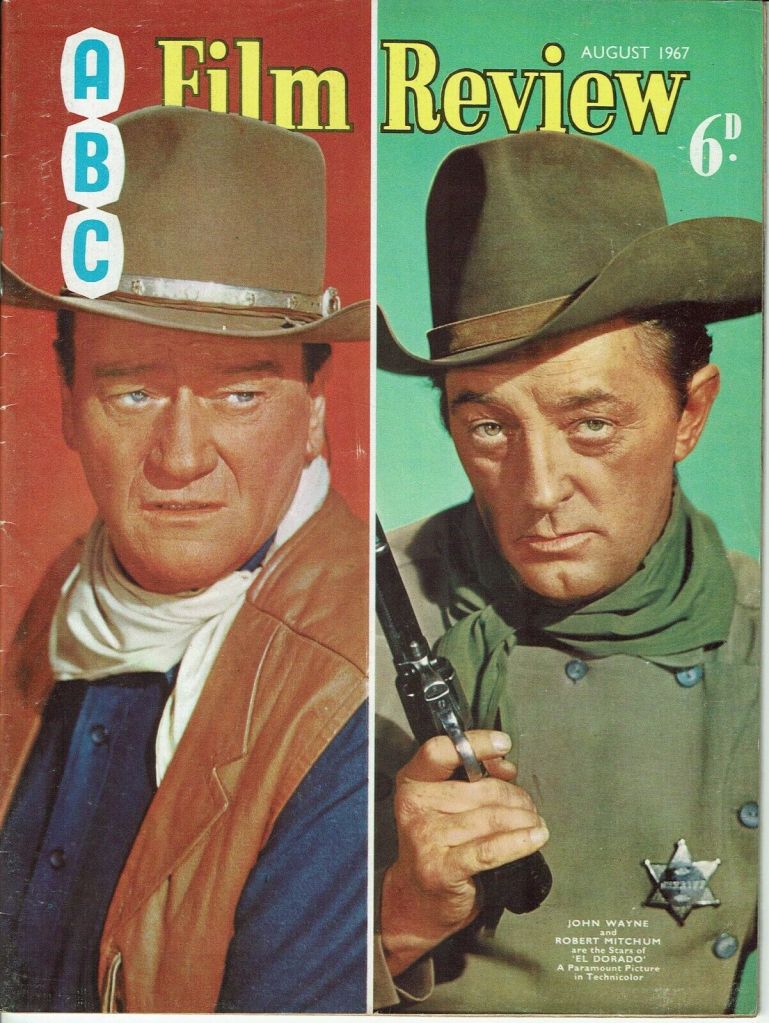

John Wayne incapacitated? Robert Mitchum a liability? The hell you say! You bring together two of the greatest male action figures only to turn the genre upside down and inside out. And I know it’s tradition for heroes to be unable to listen to their hearts, never mind deal with emotion, but it’s a heck of a stretch for them to just completely fall apart when spurned. And I know also that Duke is not invulnerable, this isn’t the MCU for heaven’s sake, and he’s been known in his long career to take a bullet, but to be shot by a woman! That’s very close to taking the proverbial.

Also, westerns usually operate on fairly tight timeframes. If the situation takes place over a longer period that’s usually because it involves a journey. Here, there’s a split of six months between the opening section and the main action, and it does kinda defy belief that the bad guys don’t make the necessary hay while the sheriff is drunk and his main assistant has scarpered.

There’s hardly a word spoken here – between the good guys again for heaven’s sake – that isn’t an insult. Never mind The Magnificent Seven (1960) this is teed up as The Bickering Quartet. And I do have to point out a couple of elements that won’t go down so well with a contemporary audience, one character imitating a Chinese, and a scene where one of our heroes is constantly interrupted in the bath by females, a twist to be sure on the usual scenario of the female lead skinny dipping in a handy pool or river, but it’s like a lame comedy sketch.

This won’t have been influenced by the spaghetti western, the first Sergio Leone game-changer wasn’t screened in the U.S. until the following year, so it’s also worth pointing out that some of the action is pretty savage, both John Wayne and Robert Mitchum indulging in the kind of mean behavior that was usually the prerogative of the villains. Wayne even cheats when it comes to the traditional shoot-out. And while there’s none of the blood-letting that later became synonymous with the genre, director Howard Hawks does something else that is far more realistic than anything that has gone before and would count as a genuine shock to our senses. The gunfire is incredibly loud. Imagine that on Imax and you’d be jumping out of your seat every few minutes.

And just in case you think this is nothing more than a remake of Rio Bravo (1959) where a gunslinger and a drunken sheriff are holed up in jail, here the jail is mostly used as a base, the good guys racing out every now and then to pick someone off. That running, too, by older guys certainly prefigures later action pictures like Taken (2008).

We need the time gap to allow Sheriff J.P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum), one of the three best gunslingers alive, to disintegrate. He goes from tough lawman keeping an unruly town in order and holding back the worst instincts of land-owner Bart Jason (Ed Asner) planning to go in mobhanded against rival rancher Kevin MacDonald (R.G. Armstrong) in an argument over water rights.

Hired gun Cole Thornton (John Wayne), one of the three best gunslingers alive, turns up for a job with said Jason but is turned off the idea when J.P. gives him the lowdown on the situation. He dallies long enough to set up the notion that he’ll try to win back saloon-owning old flame Maudie (Charlene Holt) from J.P.

Thornton moseys off to the Mason spread to give the owner the bad news. On the way back, Luke Macdonald (Johnny Crawford), Kevin’s youngest son, on guard duty, mistakes Thornton for the enemy and shoots at him. Which results in his death. So Thornton does not get a good welcome when he arrives at the Macdonald farm toting a corpse.

Turns out the young whelp, although taking bullet in the gut, committed suicide because the pain was too much and Luke had been told by his dad that he wouldn’t recover anyway and just suffer a hideous death. While the father accepts this, his daughter Joey (Michele Carey) does not and ambushes Thornton, putting a bullet in his back. Said bullet is mighty inconveniently lodged close to his spine and needs more than the town quack to remove it. Despite sparking up old feelings for said old flame and the prospect of stealing her back from old buddy J.P., Thornton doesn’t dally longer than it takes to get temporarily fixed up, bullet still in place to cause later problems.

Now the tale takes a detour. Not only has six months passed and Thornton miles away from El Dorado, but we’ve got to hold up proceedings to introduce naïve youngster Mississippi (James Caan). Howard Hawks certainly hasn’t learned the knack of the compact introduction from John Sturges a la The Magnificent Seven (1960) so we learn that this young whelp is best with the knife and has spent two years tracking down the four killers of his foster father. The last man to die happens to be an employee of Nelse McLeod (Christopher George), one of the three best gunslingers alive, on his way to take up the job Thornton turned down, a task made a helluva lot easier because J.P is now the town drunk, having hit the bottle when spurned by a woman, not Maudie I hasten to add.

Thornton heads for El Dorado with Mississippi tagging along, armed with of a sawn-off shotgun. First task is to sober up the sheriff – by fistfight and awful concoction – and stop him becoming a worse figure of fun. On the evidence here Deputy Bull (Arthur Hunnicutt) was probably one of the three best riflemen – not to mention archers – alive. He also totes a bugle.

The sober J.P. strolls into the saloon and arrests Bart Jason and sticks him in jail, and to avoid being in a complete siege situation, the quartet, sometimes as a group, sometimes a pair, sometimes alone, venture out, as I mentioned, to pick off the enemy. This allows Mississippi a meet-cute with Joey who’s planning a short-cut to justice by shooting Jason. Maudie re-enters the frame.

The bullet in the back sporadically paralyzes Thornton and J.P. is wounded in the leg so eventually the pair are hobbling around on crutches. Maudie also turns out to be a liability, taken hostage, ensuring Thornton goes to the rescue. But the bullet in the back plays up at exactly the wrong time and Thornton’s also captured, trussed up like a hog (what, John Wayne?) then traded in for the prisoner.

Having by now reduced the odds and not wanting to be caught in a siege, the quartet take the battle to the enemy, ambushing them front and back in the saloon, Thornton ridding Nelse of the notion that he and Thornton will enjoy a winner-takes-all shootout by killing him with a rifle while lying on the ground.

While it could be trimmed – television screenings generally eliminate the racist Chinese impersonation – the action when it comes is blistering. There’s a terrific scene in a tower when Bull targets the bells to disorientate the enemy with their horrendous ear-jarring clanging. And the final shoot-out is exceptionally well done.

In ways not usually gone into, the quartet are experts in their fields. Thornton backs up his horse to get out of a difficult situation, J.P. detects a man hidden behind a piano in the saloon, Mississippi stalks a potential lone assassin, Bull uses bow-and-arrow when silence is required.

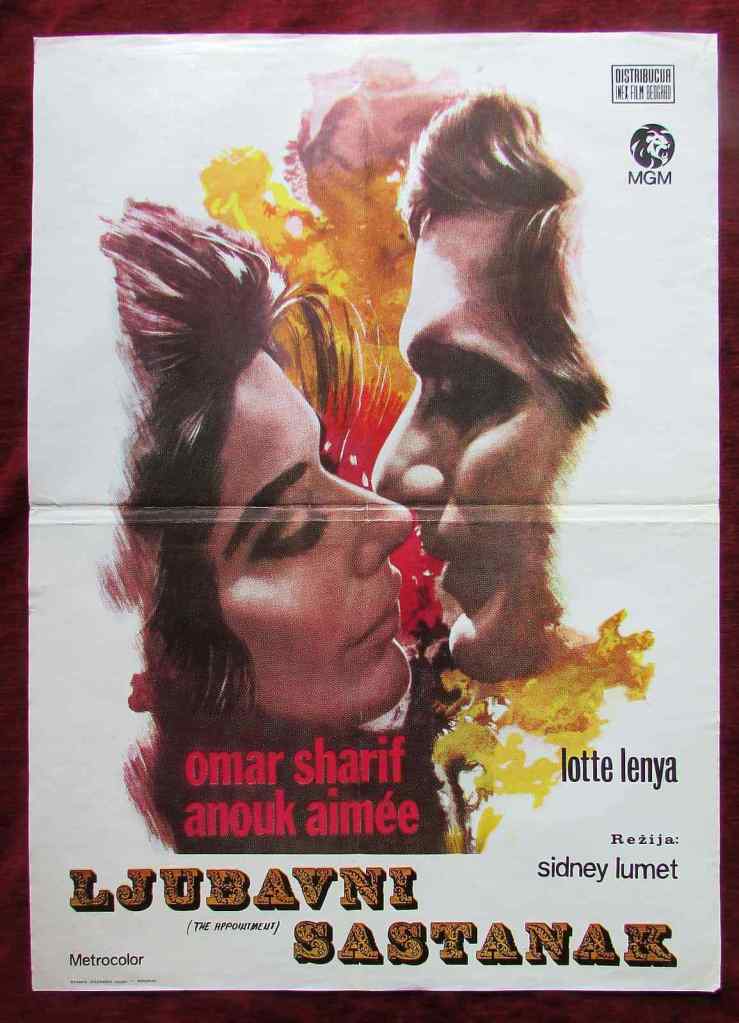

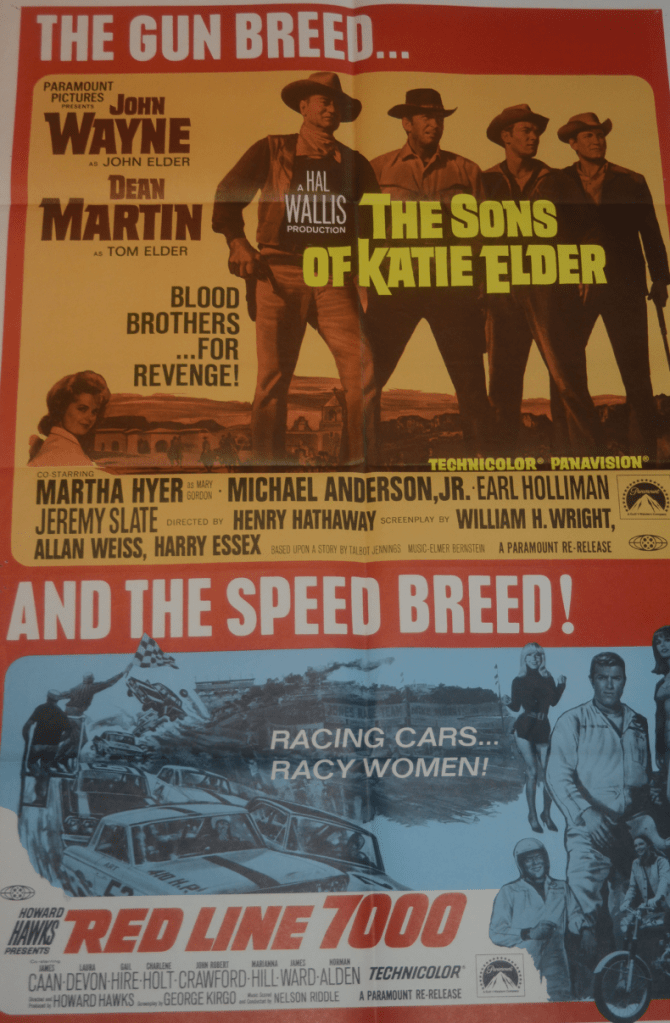

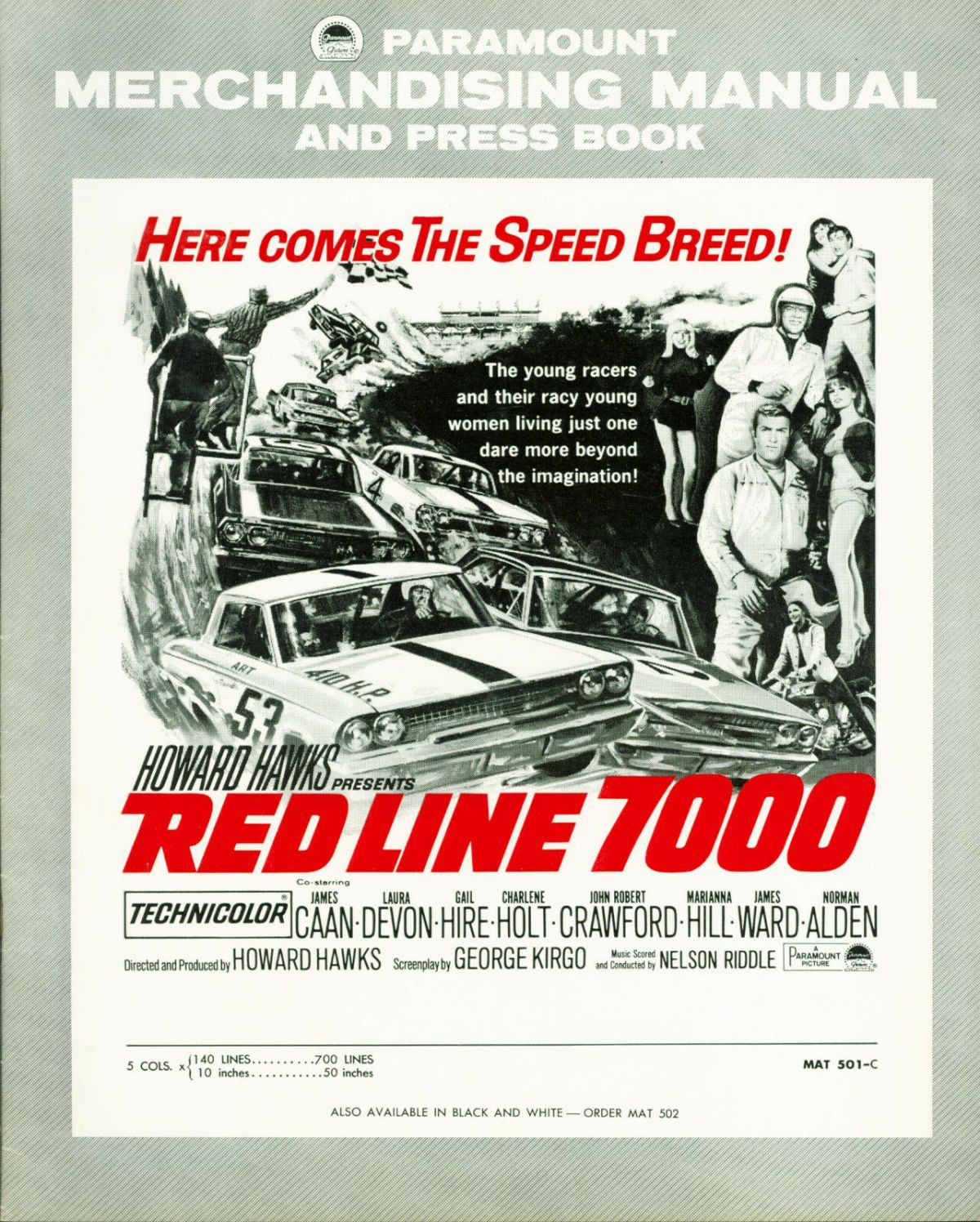

Theoretically, Robert Mitchum (Five Card Stud, 1968) steals the show as the drunken sheriff, but that’s only if you are taken in by the surface. The sight of John Wayne with his useless twisted right hand harks back to the arm in The Searchers (1956) and his one-armed rifle action predates True Grit (1969). James Caan (The Rain People, 1969) tries to steal scenes but what chance does he have with these two stars at the top of their game and past master at the scene-stealing malarkey Arthur Hunnicutt (The Cardinal, 1963). Charlene Holt (Red Line 7000, 1965) and Michele Carey (The Sweet Ride, 1968) come out honors even as do Edward Asner (The Venetian Affair, 1966) and Christopher George (The Thousand Plane Raid, 1969).

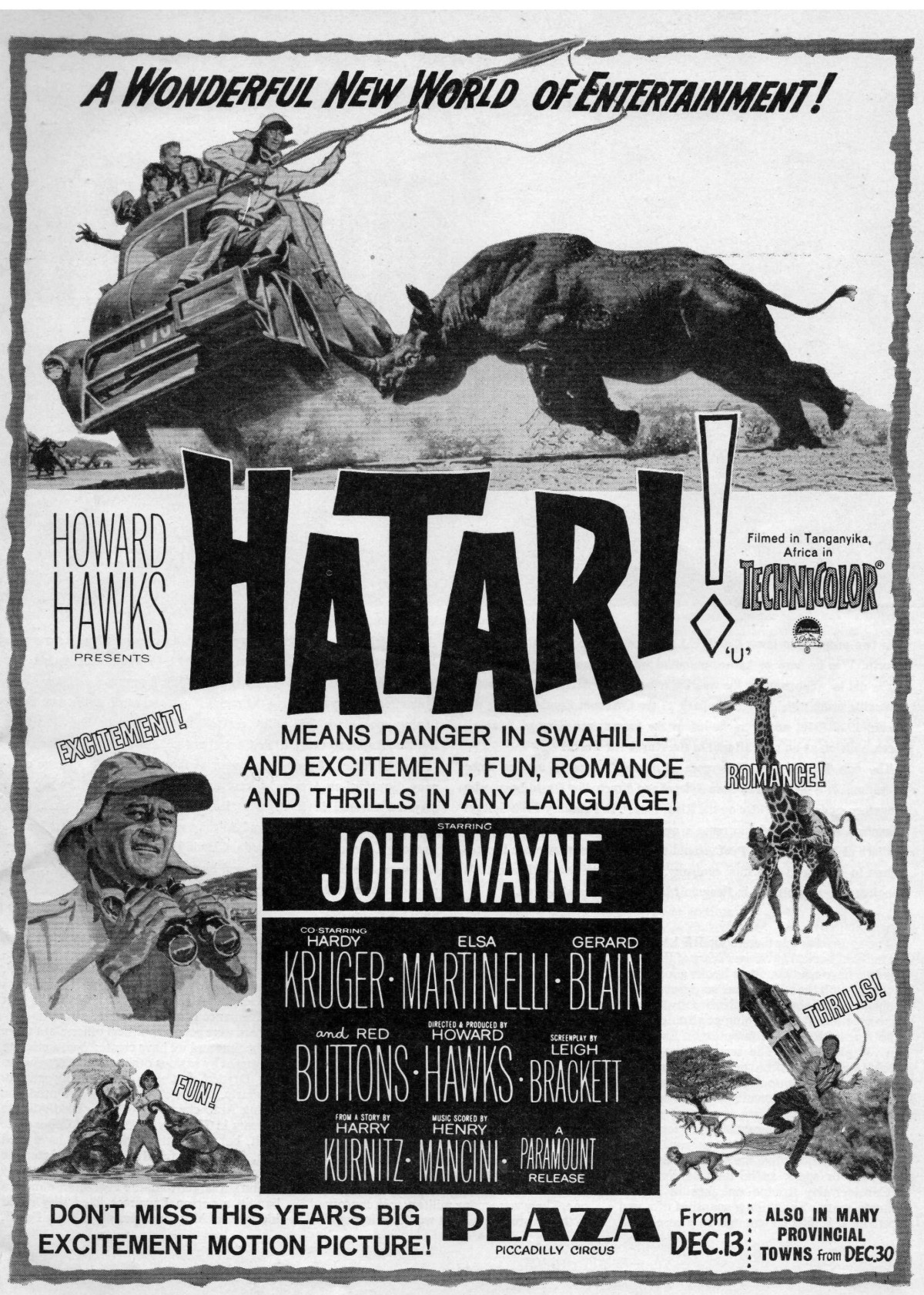

I don’t put this in the same bracket as Howard Hawks’ Red River (1948) and Rio Bravo, but it’s certainly one of the best westerns of the decade. Written by Leigh Brackett (Hatari!, 1962) from a novel by Harry Brown.

Not one to miss.