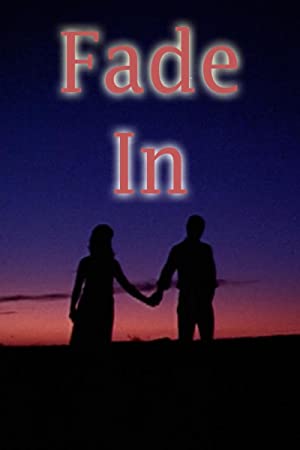

Exploitation Hollywood. Cautionary tale of young singer in the 1930s seduced by the movies only to discover she is regarded as a plaything and a profit center rather than a human being. Not highly regarded at the time despite being directed by Oscar-nominated Robert Mulligan (To Kill A Mockingbird, 1962), gained greater traction since #Me Too!

At the time the central performance by Natalie Wood (Cash McCall, 1960) seemed too much one-note, but on reflection, despite the endless popping and swivelling of her eyes (you can always see the whites, often to her detriment in acting terms), it appears a much truer reflection of a teenager caught in the headlights of the fame- and money-making machine. Christopher Plummer (Lock Up Your Daughters, 1969) delivers a devilishly restrained performance and there’s the bonus of an over-the-top turn by Robert Redford (The Chase, 1966), named Most Promising Newcomer in some parts.

The odds are stacked against Daisy Clover (Natalie Wood) from the start, living in a shack on a beachfront with an insane mother (Ruth Gordon), earning a living forging signatures on movie star portraits, but with a secret yen to become a singer. After sending a demo disk, cut in a fairground booth, to Swan Studios she finds doors opening. Raymond Swan (Christopher Plummer) turns her into a star. Having committed her mother to an institution, and for public consumption announced her dead, greedy Aunt Gloria (Betty Harford), now her legal guardian, signs her niece’s life away.

It’s almost docu-style in the telling, very few close-ups, most long shots, even in groupings the camera seems awfully far away, and the Hollywood we are shown is mostly the giant empty barns of shooting stages and the never-seen elements, like post-synching in a booth. Daisy never seems to be enjoying herself, except when, although underage, is seduced by movie idol Wade Lewis (Robert Redford) who abandons her the morning after their wedding and can’t resist a “charming boy.”

Mostly, she is the puppet, dressed in glamorous outfits, her life re-invented for the fan magazines, freedom curtailed, living in a suite in the grand mansion of Swan and wife Melora (Katharine Baird), who, it transpires, is an alcoholic and at one point cut her wrists. Most of the time Daisy just seems frozen, locked into a character she doesn’t recognize, kept at one remove from her mother, turned into a money-making machine.

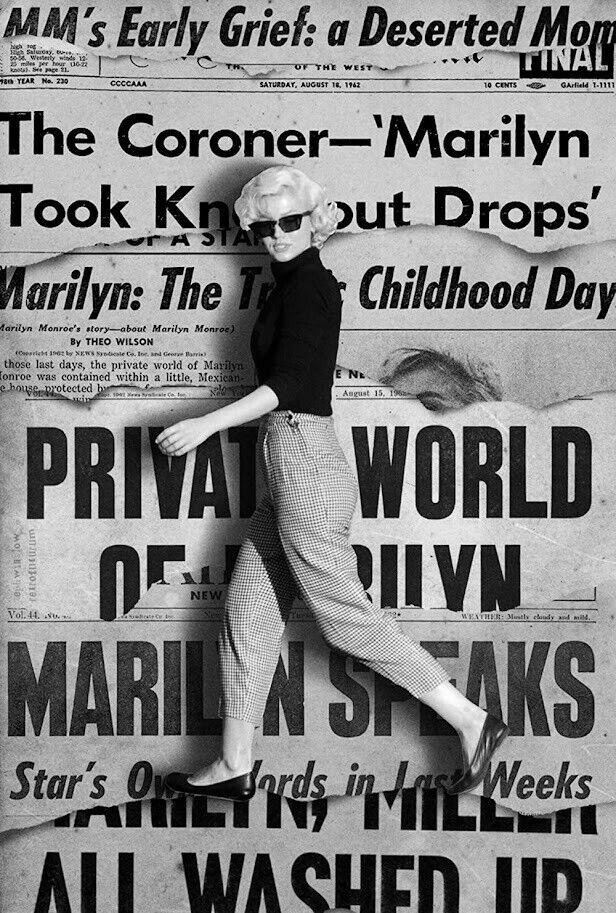

She’s too young to be a Marilyn Monroe and too old to be a Shirley Temple. The most likely template in Deanna Durbin (Mad About Music, 1938), who after being rejected by MGM, struck gold with Paramount as a 15-year-old, but, ironically, in terms of this picture, proved as hard as nails, not only negotiating contracts that turned her into the highest-earning star in Hollywood but quitting the business before it ate her up.

Daisy shifts from being able to fend off unwelcome attention from an erstwhile boyfriend while poor to being seduced, while rich and theoretically more powerful, by anyone who shows her the slightest kindness, including her boss after she’s dumped by Wade. Swan bears a close resemblance to Cash McCall, making no bones about his money-making intentions and viewing every employee in terms of profit, but using charm to mask his ruthlessness. When the façade breaks, it’s one of the best scenes.

The odds are also stacked against anyone looking good. This is a parade of the venal, everyone destroyer or destroyed. The fact that actors with no other talent earned vast fortunes from a business that was willing to underwrite their flops (Natalie Wood, herself, a classic example) and must have enjoyed some aspect of their wealth, if not in just being rescued from abject poverty, doesn’t enter the equation.

Although there is no doubt there is a Hollywood publicity machine, a lot less attention is paid to the power of the Actors PR which has managed to convince the public that no matter how much the stars earn ($20 million a picture for some) they are still poor wee souls at the mercy of terrible studios willing to gamble enormous sums ($295 million on the latest Harrison Ford, more for Fast X) on their box office potential.

But let’s not digress.

While the picture-making style is unusual, it’s worth appreciating the deliberate effort Robert Mulligan has put in to de-glamorize the star system. Brit Gavin Lambert (Sons and Lovers, 1960) wrote the screenplay from his own, more brutal, bestseller.

This cold-hearted expose is just what Hollywood deserves. That Daisy is a minor when taken advantage by Wade is mentioned just in passing, and from the actor’s perspective (it could damage his career). That vulnerable women are kept in that position was no more heinous then than it is now.