You might well enjoy this if a) you are in a very good mood, b) you love psychedelia, Pop Art and the Swinging Sixties, c) you fancy a spy film spoof or more likely d) you are a big fan of one or all concerned. Otherwise, you might be well advised to steer clear because it either takes the mickey out of a number of genres, not just espionage, or plays merry hell with narrative and character and is only loosely based on the source material by Peter O’Donnell.

Bear in mind it originated in a comic strip – later turned into a series of novels – that had more in common with the likes of Danger: Diabolik than the more straightlaced adventures emanating from DC Comics or Marvel. In particular, Modesty had a neat habit of distracting the villains by appearing topless in moments of crisis – a trick adopted in movies like 100 Rifles (1969) and El Condor (1970).

Fans of the comic strip/book may have been left indignant by the audacity of the filmmakers to introduce romance between Modesty and her sidekick Willie Gavin since in the book their relationship was strictly platonic. There was no place, in either comic strip or book, for the musical numbers that pepper the movie. And – check out The Swinger (1966) – for the notion of a character acting out a fictionalized version of herself.

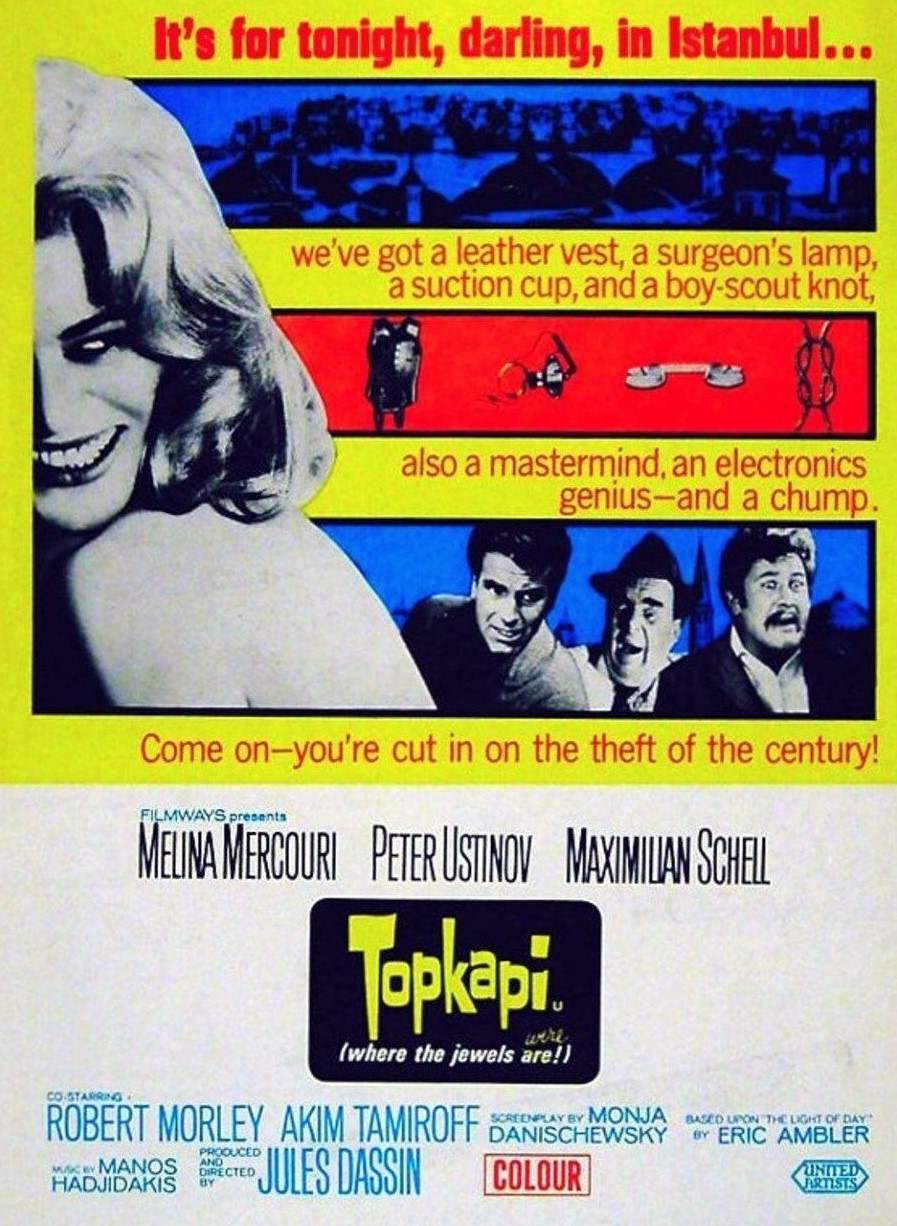

You should be aware that Modesty is a very rich version of the gentleman sleuth, an idea that belonged to the old school, of a person, such as The Saint, bored with wealth, who takes on dangerous assignments in the eternal battle between good and evil.

Anyways, on with the story.

Modesty Blaise (Monica Vitti) is hired by the British government in the shape of MI5 chief Sir Gerald Tarrant (Harry Andrews), in return for immunity for her previous crimes, to deliver a secret shipment of diamonds, part-payment for oil imports, to Sheik Abu Tahir (Clive Revill). Modesty happens to be the sheik’s adopted daughter. Meanwhile, criminal mastermind Gabriel (Dirk Bogarde), believed to be dead, has his eyes on the consignment.

Meanwhile (again), Modesty upsets current lover Hagen (Michael Craig), Tarrant’s aide, by hooking up with old flame Willie Garvin (Terence Stamp). Meanwhile (again again), Garvin hooks up with another of his old flames, magician’s assistant Nicole (Tina Marquand), who has information on Gabriel.

Various assassins employing a variety of methods are sent to kill Modesty so a good chunk of the picture is her avoiding her demise. Gabriel is a pretty touchy employer, so upset by failure that he assigns his Amazonian bodyguard Mrs Fothergill (Rosella Falk) to eliminate all such assassins. Gabriel, however, is something of a contradiction, very sensitive to violence. And just in case you are not keeping up with the plot, conveniently, the bulk of the conversations between Tarrant and his superior (Alexander Knox) will fill you in.

Through a whole bunch of clever maneuvers on Gabriel’s part, Modesty and Willie are forced to steal the diamonds themselves. And, meanwhile, Hagen is on their tail, infuriated at being jilted.

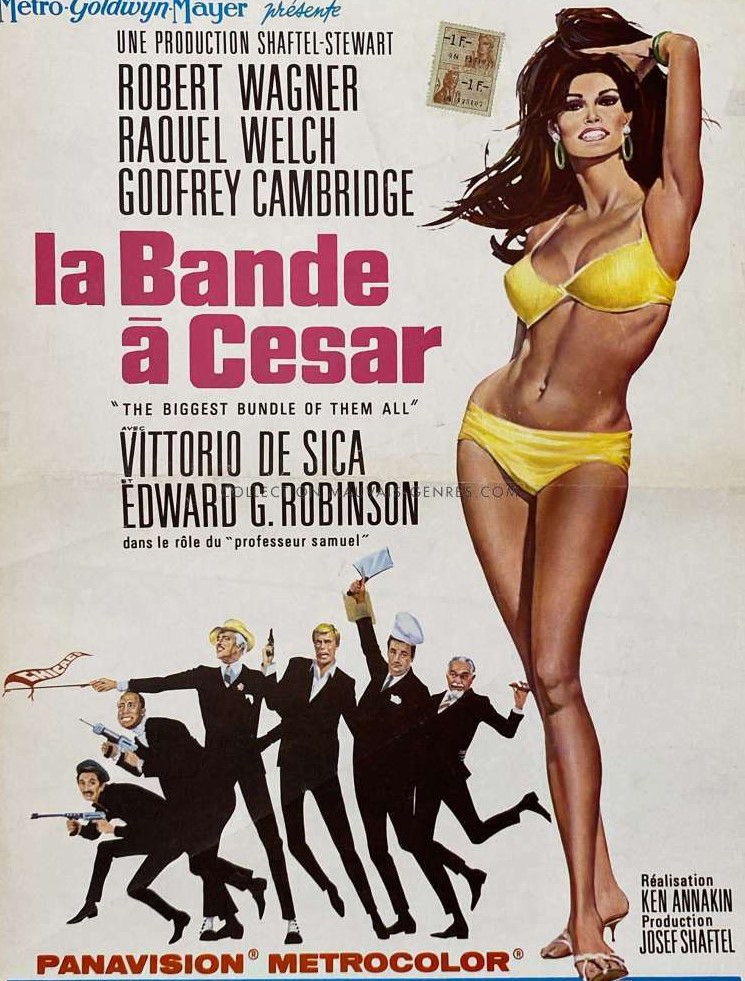

In between the umpteen shifts in plot, which basically lurches like a ship in a storm, the screen is ablaze with color. Nobody complained much when Raquel Welch found it necessary to change her bikini ever few seconds, or that a musical required continuous costume changes, and Modesty here seems to have fallen into the same pattern, the changes in outfit often so swift you imagine she has a disorder.

And be warned, this is a poster film for Pop Art, so if it’s not clothes that are being swapped, it’s décor. You might put Terence Stamp’s blond barnet in the discordant category. You can’t really complain about the plot because espionage storylines are usually something of a conjuring trick with the impossible little more than a standard mission. There’s much to enjoy if you’re of a mind and subscribe to one of the four ideas outlined in the opening paragraph and like the idea of the otherwise critical darling Joseph Losey (Accident, 1967) giving way to stylistic overkill.

Monica Vitti (Girl with a Pistol, 1968) inhabits the role with the necessary verve though Terence Stamp (The Collector, 1963) looks as if he has walked into a spoof and Dirk Bogarde (H.M.S. Defiant / Damn the Defiant!) appears still in experimental mode, having dumped the British matinee idol, unsure of what his screen persona should be. Evan Jones (Funeral in Berlin, 1966) is generally to be blamed/praised for the screenplay.

A movie for which the word confection was invented.