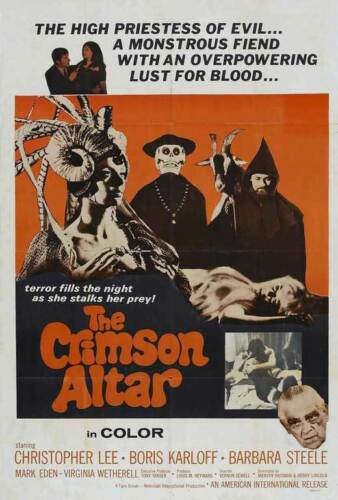

Impressively atmospheric. Cast in a cloud of fog and immersed in sound effects – bells, door swinging shut, echoing footsteps, screams, howls – and conspicuously devoid of the blood that was a Hammer hallmark. Effectively invents the Scream Queen but with a twist. With the likes of Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing and Vincent Price to accommodate, for the decade’s major purveyors of horror – Hammer, AIP and Tigon – women played a subsidiary role, mainly there to be helpless victims and scream. Here, as Hammer would later emulate, the female of the species took central stage and, therefore, screaming was at a minimum.

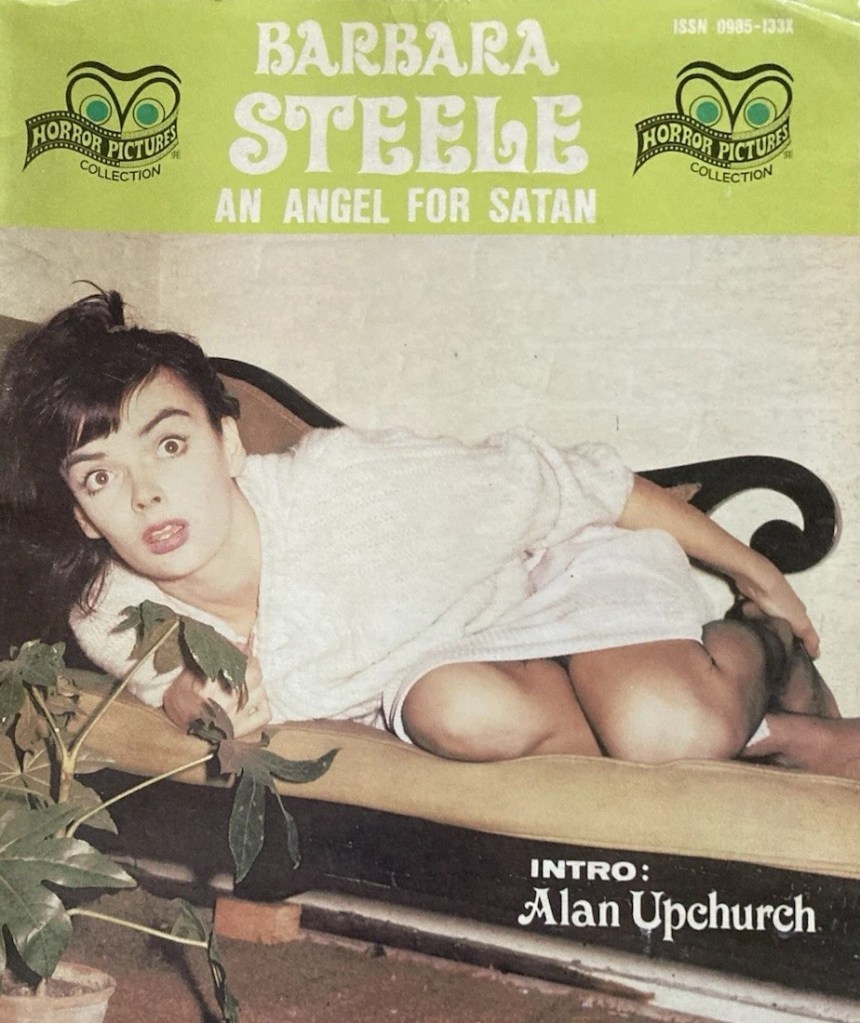

For that reason although Hammer sold Veronica Carlsen (Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, 1968) and Caroline Munro (Dracula A.D. 1972, 1972) as Scream Queens, they were not in the same league as Barbara Steele, who added mystery to glamor, and who took center stage rather than operating on the periphery, driving the narrative rather than required to be constantly rescued. Hammer took the Black Sunday template, more or less filched the story, and translated it into its Karnstein trilogy (The Vampire Lovers, 1970, Lust for a Vampire, 1971, and Twins of Evil, 1972) that allowed women to run rampant, and swapped relatively tame cleavage for nudity and sex.

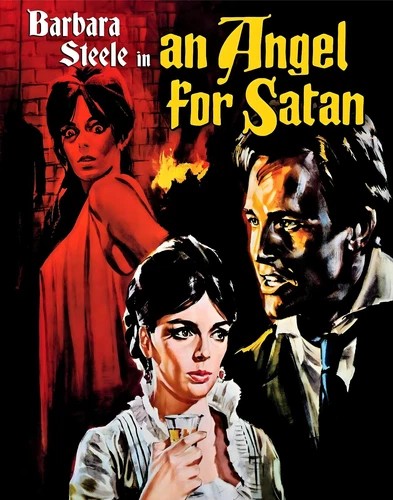

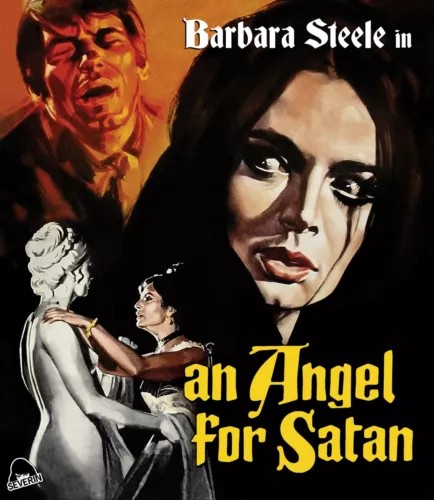

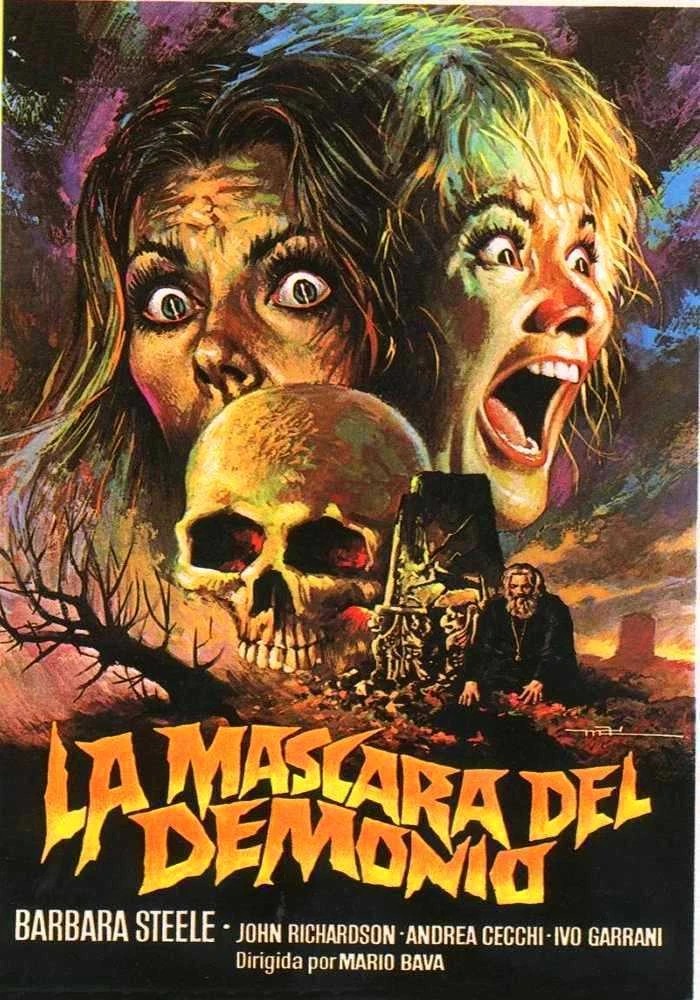

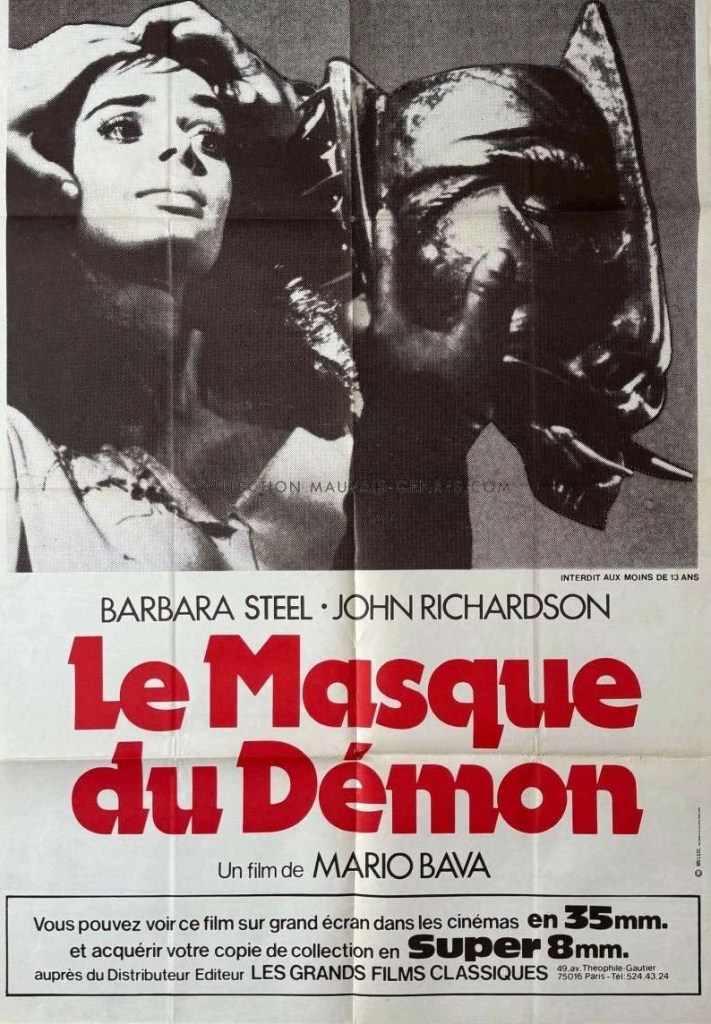

As a showcase for the horror talents of British actress Barbara Steele (Castle of Blood, 1964) – in a dual role as both predator and victim – and Italian director Mario Bava (The Whip and the Body, 1963) we are entering horror masterpiece territory. Bava brings more imagination to the table than Hammer. The steel needles of the mask affixed to witches is a fabulous invention. Victims are not drained of blood but surrender through a gentle kiss. The contents of paintings change. Rising from the dead is an explosive business rather than the traditional slow entrance.

Dr Kruvajan (Andrei Cecchi) , traveling through Moldavia with assistant Dr Gorobec (John Richardson), inadvertently triggers the resuscitation of the corpse of Princess Asa (Barbara Steele), a witch executed two centuries previously, but, crucially, avoiding being burnt to death when a sudden thunderstorm extinguished the pyre. She is able to revive, telepathically, her lover Javutich, also condemned as a witch, and together they prey on the descendants of those who put them to death, namely Prince Vadja, his daughter Katia (Barbara Steele) and son Constantin. A crucifix saves the prince first time round but soon he is slaughtered.

Kruvajan, smitten by the beauty of Asa, submits to her power and becomes her willing accomplice assisting Javutich in his killing spree. Gorobec, meanwhile, has fallen for Katia, and together with Konstantin is on hand to initially prevent the worst. But Asa has her eyes on Katia, planning to drain her of her blood and take over her body.

There are plenty close calls and the usual quota of violence, though the cleavage quotient is almost nil. That the movie climaxes in a terrific twist and an awesome visual demonstrates that Bava was a cut above the usual directors working in the genre. By the time Gorobec traces the missing Katia to the haunt of Ava, the damage has been done, although the audience doesn’t realize it. The now revived and stunningly beautiful Ava points out Katia as the witch who requires killing. And it’s only when Gorobec notices the crucifix on Katia’s neck that he realizes the bodies have been switched. Beneath her robes, Asa is a skeleton. Horror specialists spent a decade trying to top that image and it took the big-budget The Exorcist (1973) to come close.

Barbara Steele is mesmeric, exuding an exotic mysterious appeal that no other Scream Queen could match. Screenplay by Ennio De Concini (A Place for Lovers, 1969) and Mario Serandrei, better known as an editor, based on the story by Gogol.

The AIP redubbed and recut version released in the U.S. in 1961 differs significantly from the original. It was banned in Britain until 1968.

Brilliant opening, brilliant finish, all hail the two new stars of the genre