Two subjects dominate Covid-ridden Hollywood – the abject lack of new releases and the role of old films in keeping the movie pipeline flowing.

Films like Inception (2010), Hocus Pocus (1993), Jurassic Park (1993), The Nightmare Before Xmas (1993) and Star Wars Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back (1980) among a host of others have come to the rescue of beleaguered exhibitors.

But this is not the first time that old films saved Hollywood. Reissues have been doing this trick for over a century. I wrote a 480-page book about it called Coming Back to a Theater Near You: A History of the Hollywood Reissue 1914-2014 (McFarland 2016) and since the subject was ripe for discussion I was invited to become the sole guest on a hour-long podcast by Pete Turner of Oxford Brookes University.

The golden age of the reissue came in the 1960s – the true starting point being 1964 – and therefore is very relevant to this blog.

But re-releases had been part of the Hollywood landscape since 1914 and for the same reason as now – a shortage of product. At that time exhibitors scrambled to show again older films from the two dominant stars of the era – Mary Pickford and Chaplin. For the next half-century, whenever production slumped, cinema owners turned to old films. But re-releases were a battleground between studios and exhibitors. Studios complained that each rental of an old film took away revenue that should be accruing to a new picture. Even so, there was no avoiding the need to use older films to fill out programs during years of production crisis such as the arrival of sound and especially the late 1940s and early 1950s.

But by the early 1960s with television eager to devour whatever old films were available, it seemed that the days of older movies generating any decent revenue were over. Ironically enough, it was television that hastened in a new attitude to reissues. The amount of money television was willing to pay for films depended on their box office on initial release. This issue became tricky when attempting to assess the demand for films that had been big in their day like Oscar-winner Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). Television argued that interest in seeing the film on television would not be high and that should be reflected in the price it was willing to pay. Columbia begged to differ.

To prove its point, in 1964 Columbia reissued the film. It became after Gone with the Wind the second-biggest reissue of all time, generating $2.19 million in rentals (what the studio receives once exhibitors have taken their cut) which placed the film in 32nd spit in the annual box office rankings -ahead of such star-laden vehicles are The Fall of the Roman Empire with Sophia Loren and Alec Guinness, Circus World with John Wayne and Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin in Robin and the Seven Hoods. But the icing on the cake was the sum now offered by the networks – a record $2 million. That set a precedent for blockbusters like The Ten Commandments (1956) and The Longest Day (1962) to press the reissue button later in the decade prior to a television sale.

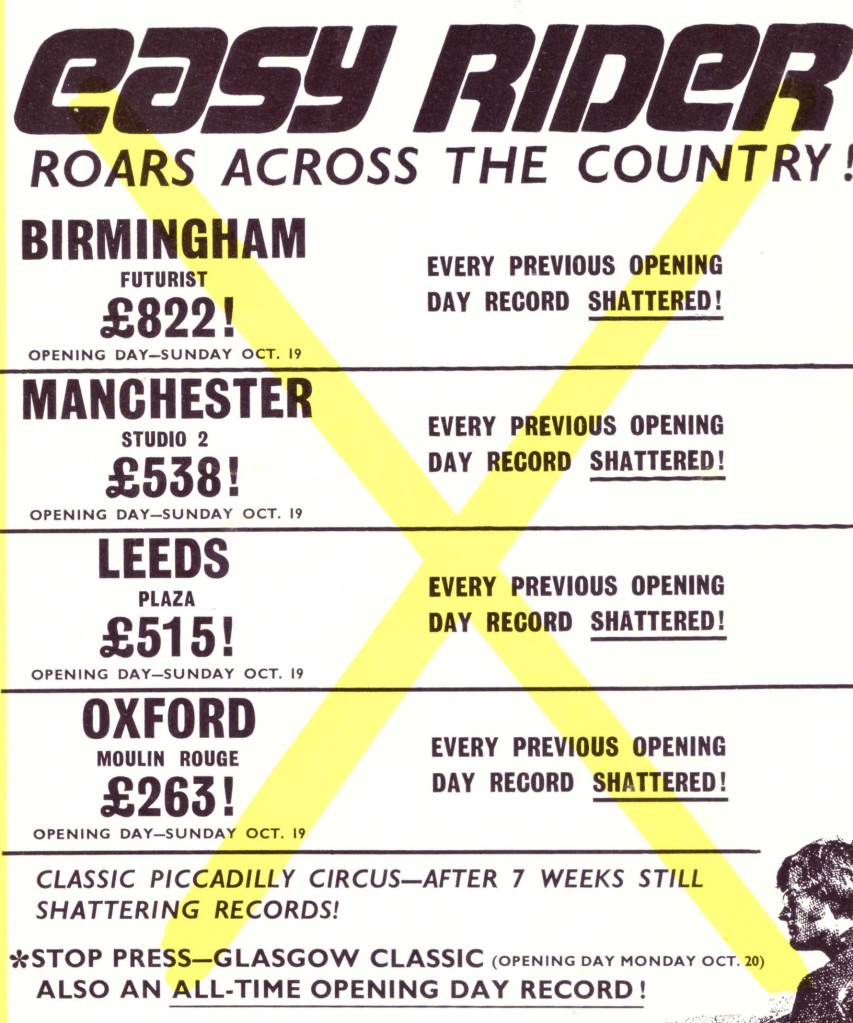

But the 1960s reissue bonanza was just beginning. In 1965 the double bill of Dr No (1962)/From Russia with Love (1963) ranked fifth in that’s year’s annual box office rankings. From then on the release of every new James Bond picture was marked by a reissue double bill. The same held true of the Pink Panthers, the Matt Helm series and the Clint Eastwood westerns. The Oscars also provided a new reissue bonus. After Sidney Poitier won the Oscar for Lilies of the Field (1963), that poorly performing picture went out again with the Oscar-nominated Hud (1963). Columbia repeated the successful format by doubling up Oscar-bait Cat Ballou (1965) and Ship of Fools (1965) both starring Lee Marvin.

It was soon open season on reissues – Lili (1953) starring Leslie Caron, Bayou (1957) now renamed Poor White Trash, the dubbed version of La Dolce Vita (1960) and the serial compendium An Evening with Batman and Robin were among the disparate successes jumping on the re-release bandwagon. Originally a flop Bonnie and Clyde (1967) only became a success when it was reissued in 1968. Disney, which had brought back its animated features on a regular basis, now turned to its live-action portfolio, cleaning up with re-runs of Swiss Family Robinson (1960) and In Search of the Castaways (1962).

Alfred Hitchcock became reissue royalty with highly profitable re-releases of Psycho (1960) and North by Northwest (1959) and double bills Marnie (1964)/The Birds (1963) and Vertigo (1958)/To Catch a Thief (1955). After box office powerhouse Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1960), two previous Elizabeth Taylor plums Butterfield 8 (1960)/Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) hit reissue box office gold. There were also unsung heroes like One Million Years B.C (1966) with Raquel Welch and Steve McQueen-Faye Dunaway romantic thriller The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). Despite being readily available on television, Humphrey Bogart and Greta Garbo oldies played in a repertory system in arthouses while MGM launched its “Perpetual Product Plan” which saw a season of older favorites like Nelson Eddy-Jeanette MacDonald musicals playing once a week for six-to-eight-weeks.

But the decade’s biggest re-run accolades were reserved for the 70mm version of Gone with the Wind (1939). Already seen earlier in the decade in 1961 where it notched up $6million in rentals, the revamped version played in roadshow for over a year before hitting the general release trail and in total generated the phenomenal $35 million in rentals.

As my book shows, the reissue story did not end there. It simply opened the floodgates. The launch of the Director’s Cut and the restoration of lost classics like Metropolis (1927) and Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) took the reissue business down a different commercial route while 3D and Imax would not have shown such commercial potential except for the reissues in those formats of films like The Wizard of Oz (1939)and Titanic (1997) not forgetting the current trend for sing-a-long revivals and films shown with an accompanying live orchestra.

Here’s the link to the podcast: https://anchor.fm/pete-turner9/episodes/The-HOMER-Network-podcast-episode-2-emmrcp