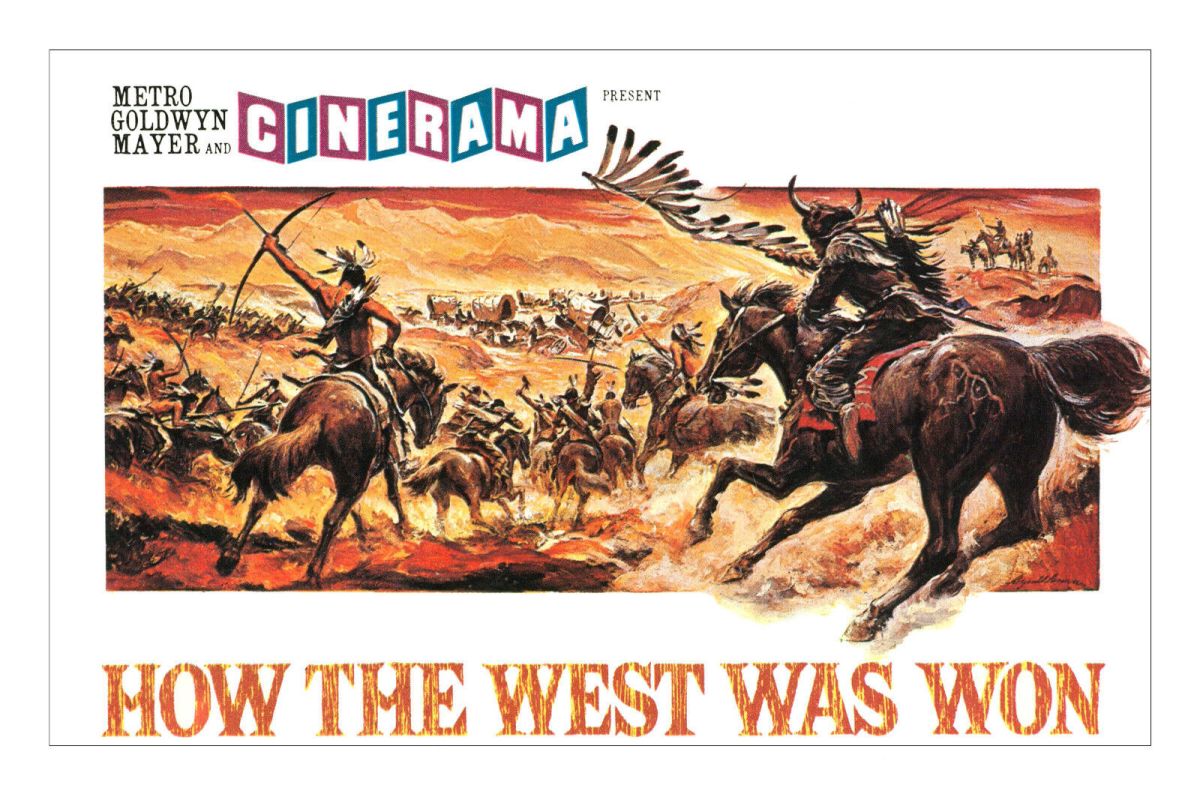

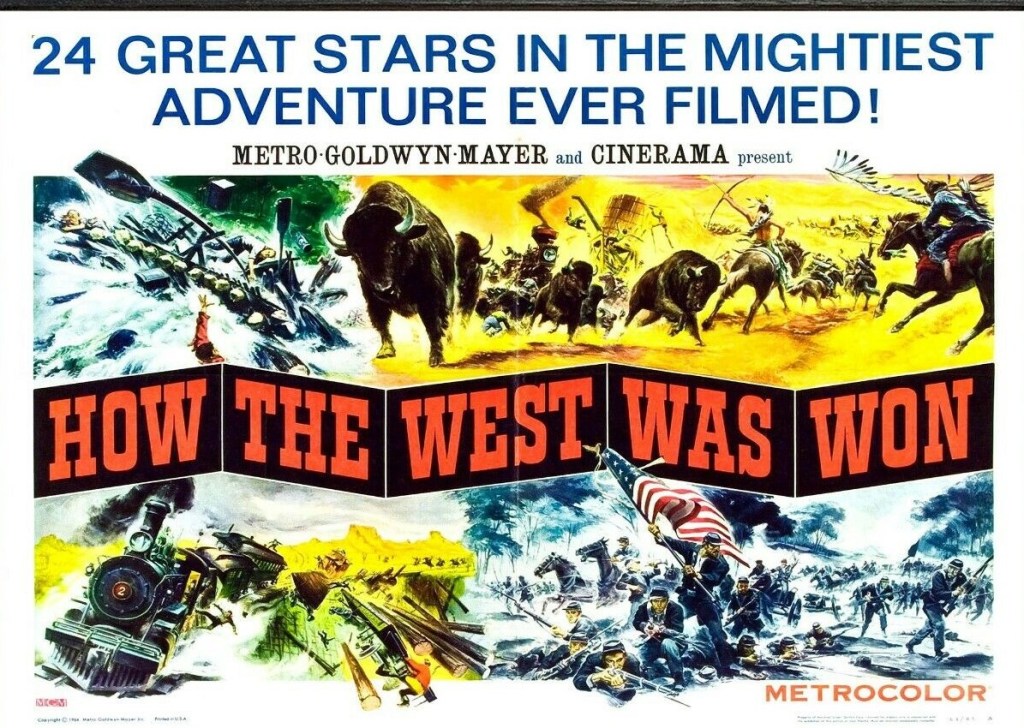

I’ve got Alfred Newman’s toe-tapping theme music in my head. In fact, every time I think of this music I get an earworm full of it. Not that I’m complaining. The score – almost a greatest hits of spiritual and traditional songs – is one of the best things about it. But then you’re struggling to find anything that isn’t good about it. But, for some reason, this western never seems to be given its due among the very best westerns.

Not only is it a rip-roaring picture featuring the all-star cast to end all-star casts it’s a very satisfying drama to boot and it follows an arc that goes from enterprise to consequence, pretty much the definition of all exploration.

Given it covers virtually a half-century – from 1839 to 1889 – and could easily have been a sprawling mess dotted by cameos, it is astonishingly clever in knowing when to drop characters and when to take them up again, and there’s very little of the maudlin. For every pioneer there’s a predator or hustler whether river pirates, gamblers or outlaws and even a country as big as the United States can’t get any peace with itself, the Civil War coming plumb in the middle of the narrative.

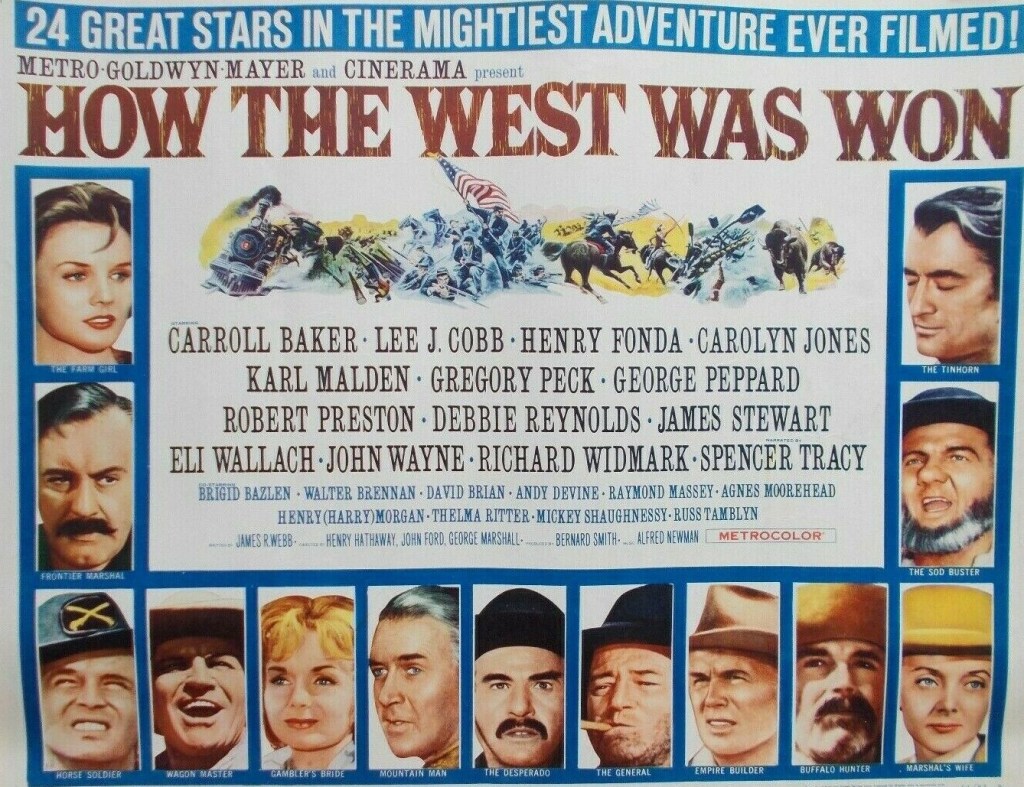

Some enterprising character has built the Erie Canal, making it much easier for families to head west by river. Mountain man fur trader Linus Rawlings (James Stewart) on meeting prospective pioneers the Prescotts has a hankering after the young Eve (Carroll Baker) but as a self-confessed sinner and valuing his freedom has no intention of settling down. But he is bushwhacked by river pirates headed by Jeb Hawkins (Walter Brennan) and left for dead, but after saving the Prescotts from the gang changes his mind about settling down and sets up a homesteading with Eve.

We have already been introduced to Eve’s sister Lilith (Debbie Reynolds) who has attracted the attention of huckster Cleve Van Valen (Gregory Peck) and they meet again in St Louis where she is a music hall turn and widow. Her physical attraction pales in comparison with the fact she has inherited a gold mine. He follows her, unwelcome, in a wagon train which survives attack by Cheyenne, but still she resists him, not falling for him until a third meeting on a riverboat.

Zeb Rawlings (George Peppard) wants to follow his father to fight in the Civil War. Linus dies there, but there’s no great drama about it, he’s just another casualty, and the death is in the passing. In probably the only section that feels squeezed in, following the Battle of Shiloh a disillusioned Zeb saves General Sherman (John Wayne) and Ulysses S. Grant (Harry Morgan) from an assassin.

Returning home to find Eve dead, Zeb hands over his share of the farm to his brother and heads west to join the U.S. Cavalry at a time when the Army is required to keep the peace with Native Americans enraged by railroad expansion. Zeb links up with buffalo hunter Jethro Stuart (Henry Fonda), who appeared at the beginning as a friend of his father.

Eve, a widow again, meets up in Arizona with family man and lawman Zeb who uncovers a plot by outlaw Charlie Gant (Eli Wallach) to hijack a train. Zeb turns rancher once again, looking after her farm.

But the drama is peppered throughout by the kind of vivid action required of the Cinerama format, all such sections filmed from the audience point-of-view. So the Prescotts are caught in thundering rapids, there’s a wagon train attack and buffalo stampede, and a speeding train heading to spectacular wreck. There’s plenty other conflict and not so many winsome moments.

Interestingly, in the first half it’s the women who drive the narrative, Eve taming Linus, Lilith constantly fending off Cleve. And there’s no shortage of exposing the weaknesses and greed of the explorers, the railroad barons and buffalo hunters and outlaws, and few of the characters are aloof from some version of that greed, whether it be to own land or a gold mine or even in an incipient version of the rampaging buffalo hunters to pick off enough to make a healthy living.

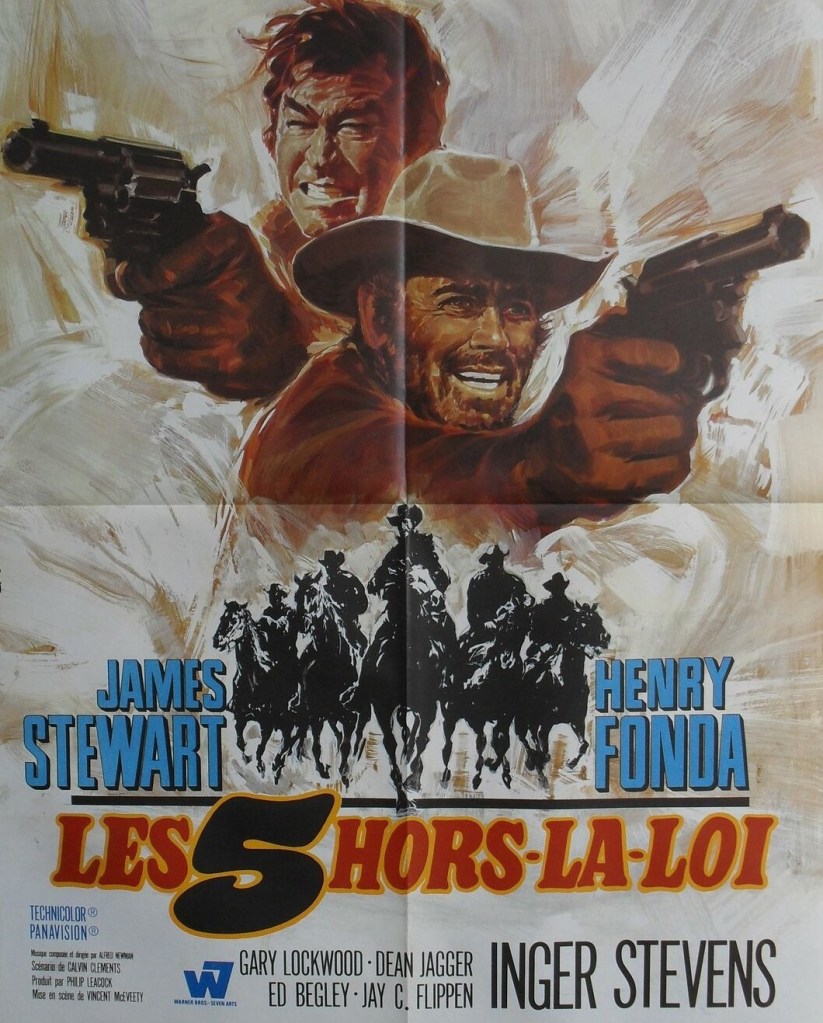

And here’s the kicker. Virtually all the all-star cast play against type. John Wayne (Circus World, 1964) reveals tremendous insecurity, Gregory Peck (Mirage, 1965) is an unscrupulous though charming renegade, the otherwise sassy Debbie Reynolds (My Six Loves, 1963) is as dumb as they come to fall for him, and for all the glimpses of the aw-shucks persona James Stewart (Shenandoah, 1965) plays a much meaner hard-drinking hard-whoring version of his mean cowboy. Carroll Baker (Station Six Sahara, 1963) is an innocent not her usual temptress while George Peppard (The Blue Max, 1966) who usually depends on charm gets no opportunity to use it. .

Also worth mentioning: Henry Fonda (Madigan, 1968), Lee J. Cobb (Coogan’s Bluff, 1968), Carolyn Jones (Morticia in The Addams Family, 1964-1966), Eli Wallach (The Moon-Spinners, 1964), Richard Widmark (Madigan), Karl Malden (Nevada Smith, 1966) and Robert Preston (The Music Man, 1962).

Though John Ford (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, 1962) had a hand in directing the picture, it was a small one (the short Civil War episode), and virtually all the credit belongs to Henry Hathaway (Circus World) who helmed three of the five sections with George Marshall (The Sheepman, 1958) taking up the slack for the railroad section.

And though you might balk at the idea of trying to cover such a lengthy period, there’s no doubting the skill of screenwriter James R. Webb (Alfred the Great, 1969) to mesh together so many strands, bring so many characters alive and write such good dialog. Bear in mind this was based on a series of non-fiction articles in Life magazine, not a novel, so events not characters had been to the forefront. Webb populated this with interesting people and built an excellent structure.

I’m still tapping my toe as I write this and I was tapping my toe big-style to be able to see this courtesy of the Bradford Widescreen Weekend on the giant Cinerama screen with an old print where the vertical lines occasionally showed up. Superlatives are superfluous.