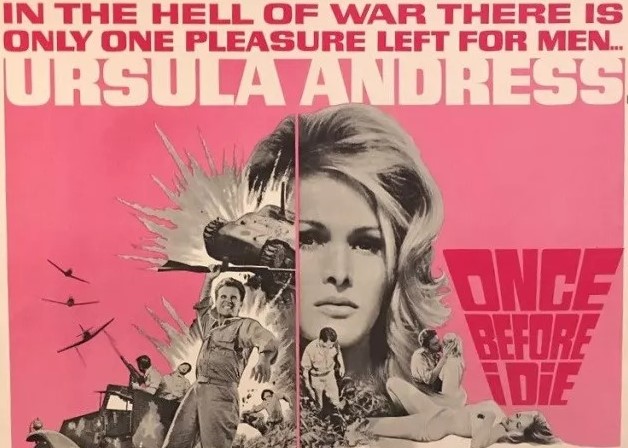

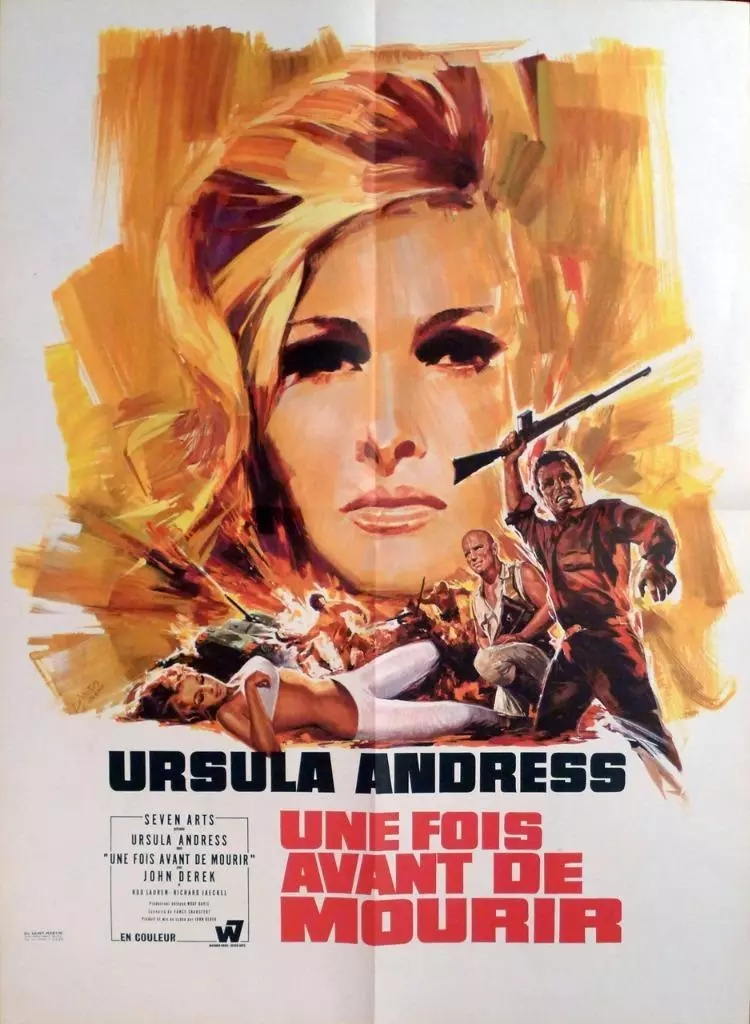

Nobody ever took Ursula Andress seriously as an actress. Ditto the directorial skills of her one-time husband John Derek (Bolero, 1984). Their combination was viewed as a cosmic joke. And it doesn’t start well here, the credits little more than a paean to her beauty, hair rippling in the wind etc, so much so you wouldn’t be surprised to find her later on running in slo-mo through a cornfield. The opening sequence couldn’t be more Raquel Welch, Andress sporting a white bikini as she shoots the rapids. And the premise looks like little more than a wartime western.

Instead…

Technically, this is surprising, ocasionally astounding, as the director makes use of the kind of image layering that attracted kudos for Francis Coppola in Apocalypse Now (1979) and with one stunning sequence shown entirely, in close-up, through the eyes of the actress. Andress is far from eye candy. Opportunities to show her naked or at least soaked to the skin, obligatory scenes set in water, are passed over. Instead, she is the camera’s conduit. The innocent bystander responding to war, and sharing in the shock of the youngsters, mostly virgins, who will never see a naked woman before they die.

Having to literally deal with the title should be the only false note and yet strangely enough there’s a haunting lyrical quality in the contrast between her, in the midst of battle, acquiescing to the shameful desire of a 22-year-old soldier to be kissed and his colleagues’ glee at burning to death the occupants of an enemy tank. An act of humanity set off against raw brutality.

The set-up is simple enough. Just after Pearl Harbor, a group of polo playing soldiers in the Phillippines are strafed by Japanese planes. Cavalry leader Bailey (John Derek) and his troop set off by horseback cross country for Manila. He sends his girlfriend Alex (Ursula Andress) off in the same direction in her ritzy car. Against instructions, she loads up her car with puppies and refugees, an old lady and a child, and when she gets stuck, Bailey allows the trio to accompany the soldiers to safety. When they reach a village, her linguistic skills come in handy, pinpointing a Frenchman and his native girl, purportedly translating, as lying about food supplies.

In rooting out a bloodied teddy bear, Bailey is accidentally killed and for the rest of the picture Alex is in something of a catatonic state, but doing her best to keep up soldier morale, as attendant to the worries of the young, fearing death, as to the more experienced gung-ho shaven-headed Custer (Richard Jaeckel) who welcomes a hero’s demise. By the end, she is a combatant, shooting an enemy soldier.

By taking Alex as the cinematic focus, the director can dispense with the usual tropes of a battle-weary squad in wartime. So, beyond the youngster’s confession, we learn nothing of the soldiers’ lives, and that, too, is somehow refreshing, as going down that route at best seems like a vain attempt to make audiences sympathize with unsympathetic characters, and at worst, is a delaying device.

All you need to know is that guys who would otherwise be larking about, drinking beer, telling tall stories or playing polo, are vicious in war, gunning down as if a communal firing squad a captured grunt, so trigger happy they shoot one of their own in the middle of the night, so careless they are liable to drop a grenade at their own feet.

And, much to my astonishment, there’s dialog and scenes Tarantino would be proud of. Custer explaining that he shaves his head “to get rid of every hair” is the kind of line that in a more acclaimed picture would be noted. Custer again, accused of making up a story that he has killed a bundle of Japs, looks initially as if he believes himself guilty of too fertile an imagination until he interrupts a chat between two disbelieving officers by chucking an enemy corpse onto their laps.

And there’s genuine screen charisma between Alex and Bailey, a wonderful scene where she takes gentle umbrage at being scolded for refusing to obey orders, but nothing played out to the brim, everything understated, the actions of a couple who don’t need to display their love to the world because they are already committed.

The Virgin Soldiers (1969) played the central theme for laffs but didn’t achieve an ounce of the truth expressed by the raw youngster, who’s ashamed to be revealing such fears to a woman, and to be even asking her to relieve them, and of the dumbness to be muddying his thoughts in a life-and-death situation with fantasies about sex. You can certainly argue with the notion that women in wartime are obliged to have sex with any passing soldier (who sometimes take without asking) who could die a virgin, and taking that into consideration, this shouldn’t work at all. It’s only a kiss and hand-holding after all, and she’s not maternal about it, or even pitying, and after all, deprived of a future husband, she also needs solace.

I mentioned before about finding suprises in my trawl through this decade’s movies and there couldn’t be a bigger surprise than this which must have lain unseen on my shelves for years as I dreaded inflicting upon myself another movie by the director of Tarzan the Ape Man (1981).

But astute direction and the determination to allow Andress to act, to show scenes through her eyes, the sign of any great actress, pay off. Career-best performance from Richard Jaeckel (The Devils’ Brigade, 1968), no show-boating here either. The budget restricts the action, but, oddly enough, that’s to the film’s benefit as it allows it to play off Andress more.

Well worth a watch.