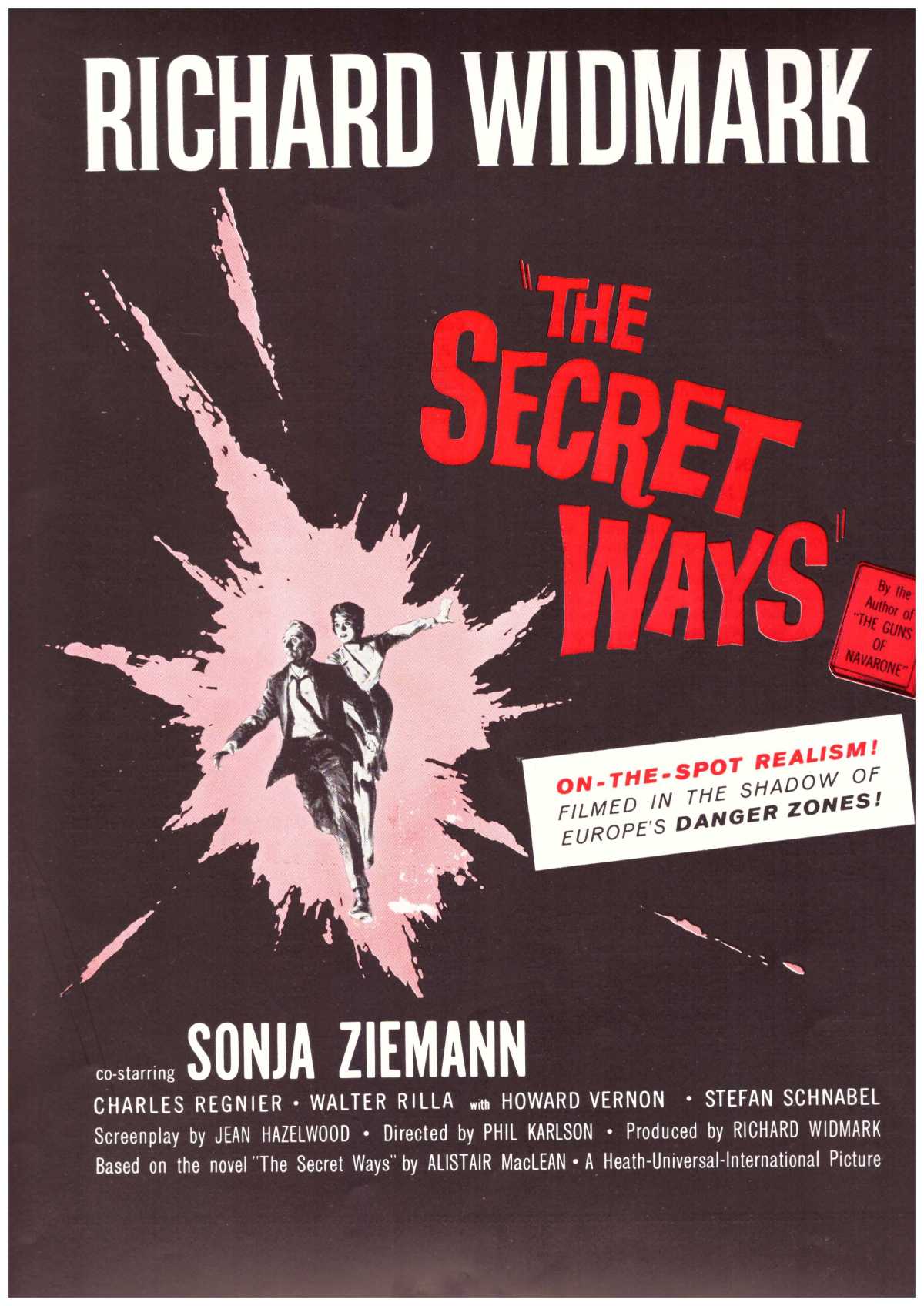

Curious about what happened to Haya Harareet, Charlton Heston’s leading lady in Ben Hur (1959), filmed in 70mm glorious color, I happened across this neat twisty British thriller filmed in standard ratio and black-and-white. Turned out to be put together by the Basil Dearden/ Michael Relph combo and starring Stewart Granger, one-time star of MGM extravaganzas like King Solomon’s Mines (1951) and clearly now atoning for failing to hit the box office mark often enough for Hollywood’s liking.

Driven by a brilliant plot, whose resolution I defy you to guess, it climaxes with three stunning twists, the first story-driven but the others landing a no less effective emotional and human punch. I should warn you right away that Harareet is not in the picture as much as you would expect given that she took second billing. That’s no surprise, really, since on her first entrance, as wife Nicole, she walks out on husband John Brent (Granger) citing his illicit romantic liaisons.

Though driving a swanky car and living in a big London house, Brent , a top-level shipping executive, is one harassed individual. He is being blackmailed by alcoholic dentist Ralph Beldon (Norman Bird). When the shipping company’s safe is robbed of £130,000 (equivalent to £3 million today), suspicion falls on Brent, one of only two employees with both keys and the combination. Enter about-to-retire chain-smoking Detective Superintendent Hanbury (Bernard Lee, shortly to achieve global fame as “M” in the Bond series).

Constantly wreathed in a cloud of smoke, Hanbury’s investigation leads to various suspects – the other keyholder Charles Standish (Hugh Burden) whose job is at risk, interior designer Clive Lang (John Lee) who is too familiar with Nicole and friend Alan Richford (Conrad Philips) who is secretly in love with her. All have good reason to be responsible for the theft, not least Nicole because of Brent’s habit of talking in his sleep and in trying to memorize ever-changing safe combinations constantly running them through his head, conscious or unconscious.

To add to the complications, Brent has a mysterious past. In addition, a masked gunman pops up from time to time. So, although Brent remains the prime suspect, Hanbury, with an investigator’s vigilance and attention to detail that Hercule Poirot would be proud of, uncovers clues that point elsewhere. Pretty soon, Brent is on the run, first to France, where he is arrested, and then, after escaping custody, through the murky streets of Soho trying to locate a girl to whom he might have given the combination while asleep. He, too, discovers some unpleasant truths far closer to home.

Dearden does a brilliant job of setting up the mystery, a dab hand, too, at serving up multiple red herrings, as well as a spot of sleight of hand, not least when the music intrudes too loudly in old-fashioned manner as if to point the finger, and the audience’s attention, in a misleading direction. Sure, it’s a low-budget affair by Hollywood standards and indeed by Dearden/Relph standards (big-budget roadshow Khartoum, for example), and the black-and-white photography is for financial rather than artistic reasons, but it is superbly done and keeps you guessing to the end. Granger is at his suave best. Harareet, all fur coat and steely resolve, gives a good performance. Bernard Lee is an excellent British copper, hoping to end his career on a high note, patiently probing suspects, and there is a good turn from Norman Bird as the dodgy dentist and a fleeting appearance by Willoughby Goddard as an equally dodgy hotel manager.

Except there’s no extraneous violence, it could be a latter-day film noir.

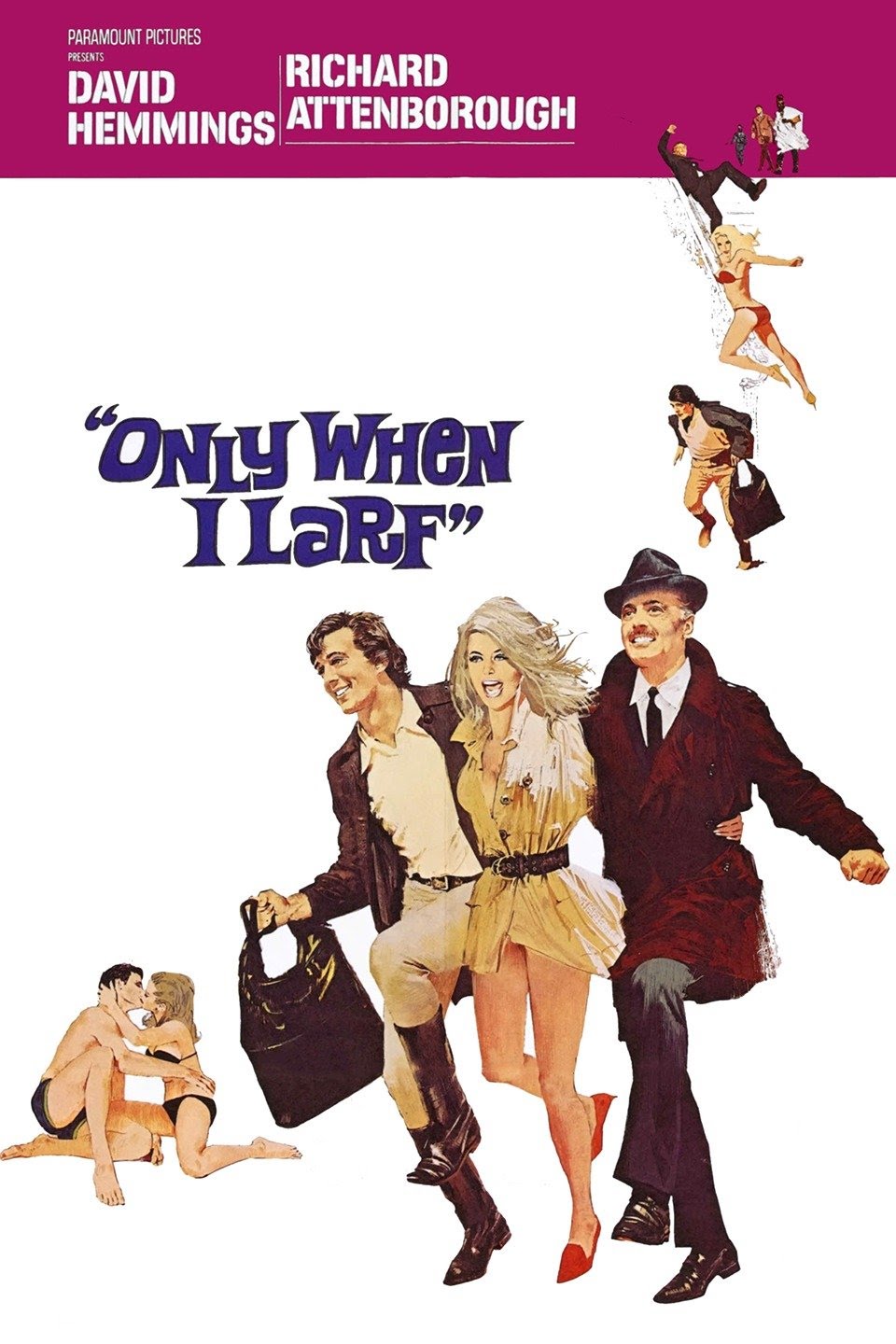

Catch-Up: Other Dearden/Relph films reviewed in the Blog are: Masquerade (1965), Khartoum (1966), Only When I Larf (1968) and The Assassination Bureau (1969). Stewart Granger was also reviewed in The Secret Invasion (1964).