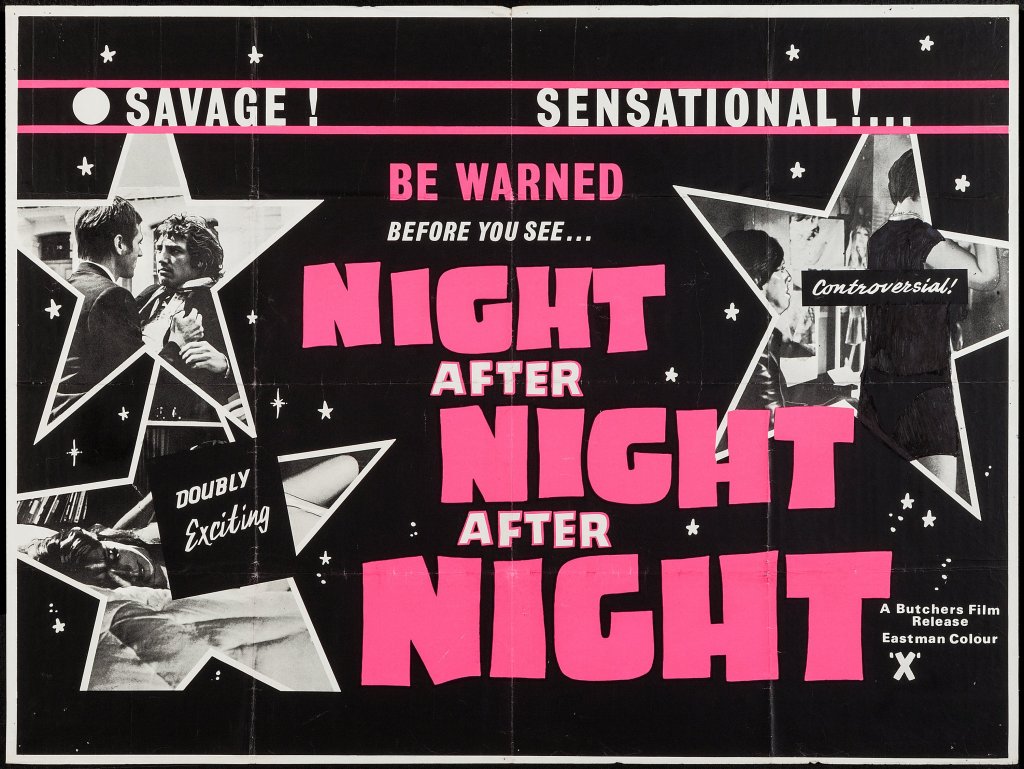

So underrated it doesn’t even feature on Wikipedia’s chart of 1960s crime pictures, this tight little gem, with an early reflection on police brutality, a dream cast, violence in slow motion (prior to The Wild Bunch, 1969, mind you) and a stunning score from Jerry Goldsmith, is definitely in need of resurrection. Astonishing to realize that cop pictures had fallen so out of fashion, that this was the first Hollywood cop film of the decade – outside of a drama like The Chase (1966) – the entire previous output focusing on gangsters with a rare private eye (Harper, 1966) thrown in. With none of the vicious snarl of Madigan (1968) or the brutality of Coogan’s Bluff (1968), this was more in keeping with the later In the Heat of the Night (1967) in terms of the mental and physical barrage endured by the cop.

In thick fog on a stakeout for a serial killer at an apartment block Sgt Tom Valens (David Janssen) kills a potential suspect, wealthy Dr Ruston. Valens claims the suspect was reaching for his gun. Only problem – nobody can find the gun. Up on a potential manslaughter charge, Valens is pressured by boss (Ed Begley), lawyer (Walter Pidgeon) and wife (Joan Collins) to take the rap and plead guilty. The public and media rage about police brutality. Putting Valens’ testimony in doubt is a recent shooting incident, which left Valens with a stomach wound, and which may have clouded his judgement.

Although suspended, Valens has no alternative but to investigate, interviewing elderly patient Alice (Lillian Gish) whom the doctor was visiting, patient’s neighbour playboy pilot Walt (George Grizzard), doctor’s assistant Liz (Stefanie Powers), doctor’s wife Doris (Eleanor Parker) and doctor’s stockbroker (George Sanders) without nothing to show for his efforts but a savage beating, filmed in slow motion, inflicted by the doctor’s son and pals, and a further attempt on his life. He gets into more trouble for attempting to smear the doctor as an abortionist (a crime at the time).

The missing gun remains elusive though the direction at times suggests its existence is fiction. The detection is superb, red herrings aplenty, as Valens, the odds against him cheating conviction lengthening by the day, a trial deadline to beat, everyone turning against him, openly castigated as the killer cop, struggles to uncover the truth. And it’s clear he questions reality himself. He has none of the brittle snap of the standard cop and it’s almost as if he expects to be found guilty, that he has stepped over the line.

Along the way is some brilliant dialogue – the seductive drunk wife, “mourning with martinis” suggesting they “rub two losers together” and complaining she has to “lead him by the hand like every other man.” Cinematography and music combine for a brilliant mournful scene of worn-down cop struggling home with a couple of pints of milk. The after-effects of the stomach injury present him as physically wounded, neither the tough physical specimen of later cop pictures not the grizzled veteran of previous ones.

David Janssen (King of the Roaring 20s, 1960) had not made a picture in four years, his time consumed by the ultra-successful television show The Fugitive, but his quiet, brooding, internalized style and soft spoken manner is ideal for the tormented cop. This also Joan Collins (Esther and the King, 1960) first Hollywood outing in half a decade.

Pick of the supporting cast is former Hollywood top star Eleanor Parker (Detective Story, 1951) more recently exposed to the wider public as the Baroness in The Sound of Music (1965) whose slinky demeanor almost turns the cop’s head. Loading the cast with such sterling actors means that even the bit parts come fully loaded.

In the veteran department are aforementioned famed silent star Lillian Gish (The Birth of a Nation, 1915), Brit George Sanders (The Falcon series in the 1940s), Walter Pidgeon (Mrs Miniver, 1942) also in his first film in four years, Ed Begley in only his second picture since Sweet Bird of Youth (1962) and Keenan Wynn (Stagecoach, 1966). Noted up-and-coming players include Stefanie Powers (also Stagecoach), Sam Wanamaker (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965), George Grizzard (Advise and Consent, 1962) and Carroll O’Connor (A Fever in the Blood, 1961). American television star Steve Allen (College Confidential, 1960) plays a hypocritical pundit.

A sophomore movie for noted television director Buzz Kulik (Villa Rides, 1968), this is easily his best picture, concentrating on character with a great eye for mood. Screenwriter Mann Rubin (Brainstorm, 1965) adapted the Whit Masterson novel 711 – Officer Needs Help. The score is one of the best from Jerry Goldsmith (Seconds, 1966).

Has this emanated from France it would have been covered in critical glory, from the overall unfussy direction, from the presentation of the main character and so many memorable performances and from, to bring it up once again, the awesome music.

Worth catching on Amazon Prime.