Stereotypical Englishman reinvented. Where the suited-and-booted traditional British gent, umbrella at the ready, moustache awaiting twirling, bristling with pomposity, usually of military background and inclined towards the pedantic, was treated as a figure of fun, here in a marvelous conceit he is instead catnip to the ladies. You could imagine this was somewhat prophetic given the imminent arrival on Hollywood shores of such testosterone-charged figures as Sean Connery, Richard Harris et al.

All the elements that previously pointed to mickey-taking – impeccable manners, a sense of fair play anathema in the cut-throat American world, respect extended towards the opposite sex – are here presented as such ideals that the entire female population of a small town is swooning at the feet of its only known Englishman.

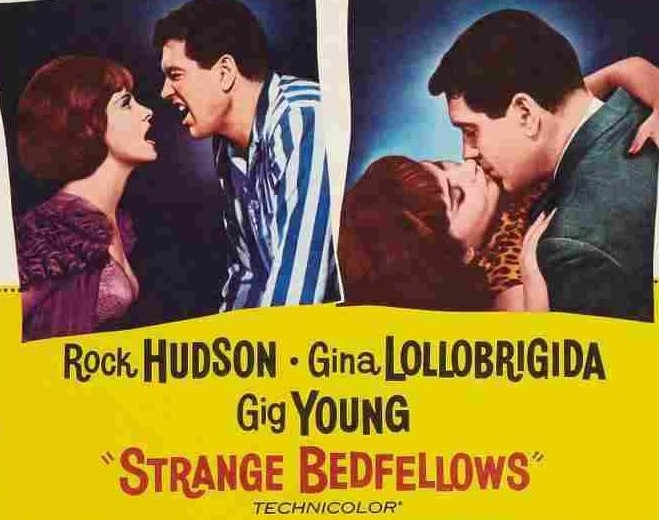

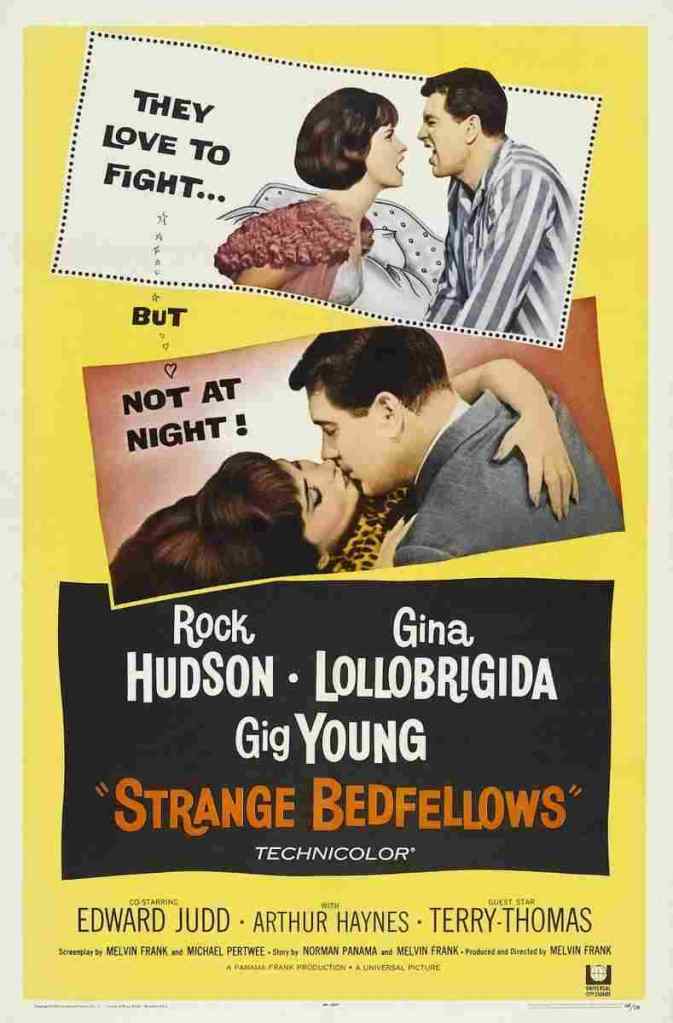

What’s more, director Frank Tashlin (The Glass Bottom Boat, 1966) doesn’t ask star Terry-Thomas (Arabella, 1967) to lampoon himself, as would often later be the case, where the actor was called upon to play an overstuffed romantic fantasist of the Bob Hope variety or presented as comedic villain or overacting butler. Instead, Terry-Thomas plays it straight, oozing astonishing charm that allows the slapstick and farcical ingredients to work a treat.

Sure, it’s mostly a dressed-up farce, people hidden in cupboards and under beds, doors slamming in faces, faces drenched in cake, and in a sharp swipe-left on gender equality, the man, rather than the woman, mostly seen in a state of undress.

Professor Patterson (Terry-Thomas) throws his adoring mostly adorable students into a tizzy when they discover he is engaged to actress Helen (Celeste Holm) currently residing in Paris. They met when the academic rented her beach house which is where Libby (Tuesday Weld) comes in. Astonished to discover a stranger in her mother’s house, Libby doesn’t let on she’s Helen’s daughter and instead pretends to have escape from juvenile detention. Helen has so far balked at telling her lover she has a 17-year-old daughter by a previous marriage.

Professor’s young neighbor, law student Mike (Richard Beymer), takes a shine to his unwelcome guest, but he’s mostly there to add complication to complication.

Usually, in these farces, it’s the guilty man trying to hide his various lovers from one another, hence stowing them away in cupboards and beds and whatever. But here the professor is a determined innocent who has to stoop to such shenanigans to pretect his integrity. But not only is he assailed by Libby but also by student Liz (Ann Del Guercio) who lets down his tyres so she can run him home and neighbor Gladys (Francesca Bellini) who makes eyes at Mike as a way of infiltrating Patterson’s defences. Added complications are a suspicious cop and a rival academic.

So when Patterson is not trying to keep the various female invaders from discovering one another, or the cop or Mike from finding them stashed away, he’s trying to fruitlessly explain how he has been snagged by the aforesaid predatory women. And of course when his fiancee returns there’s no queston she’ll catch him in some questionable act.

In some senses this is pretty formulaic stuff but it is brightened immeasurably by some choice lines (“I don’t take money from strangers unless I steal it” and “either you get a smaller bone or I get a bigger dog”), the occasional madcap situation (one of his suitors eating a slice of cream came while on a vibrating slimming machine and Mike discovering how Libby fed him a line), but mostly by the spirited playing of Terry-Thomas and Tuesday Weld. Apart from a small part in Tom Thumb (1958) this was the actor’s introduction to Hollywood and it says a lot for his talent that he’s entirely believable as the kind of charmer that women flock to.

Tuesday Weld (Pretty Poison, 1968) is more than glamor on legs and finesses her first top-billed role into surprising depths beyond the obvious enthusiastic ingenue, especially given her Ann-Margret-style shake-your-booty introduction, suggesting talent to burn. Richard Beymer (West Side Story, 1961), who was holding a real-life candle for Ms Weld, is little more than eye candy for the female gaze. And if none of this trio is sufficient to hold your attention, there’s a cute dog.

Frank Tashlin occasionally made films with more acerbic bite, but this isn’t one of them. It sticks to a magic formula that works mostly thanks to the two principles.

Raised up a good notch by the revelatory performance by Terry-Thomas, his drunk scenes are just superb and unusually played, and you probably can guess from this where Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) got its rain-soaked proposal scene.

Tremendous fun.