A pratfall still works wonders. An open door or window, anything that happens to be on the floor, or for that matter any object of any description – billiard cues, for example – within easy reach offers the opportunity for havoc – and a steady stream of laffs. Which is just as well, because this complicated farce, which might get a few extra brownie points today for its satire on serial killers, doesn’t do the movie any favors.

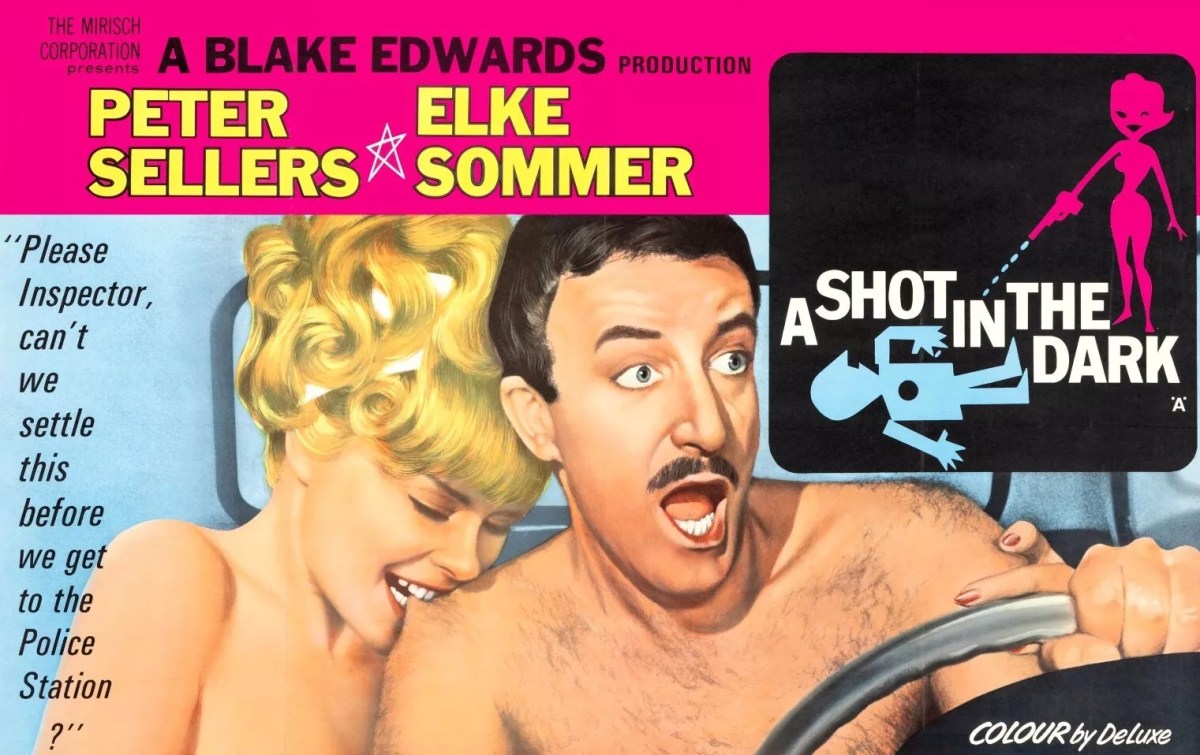

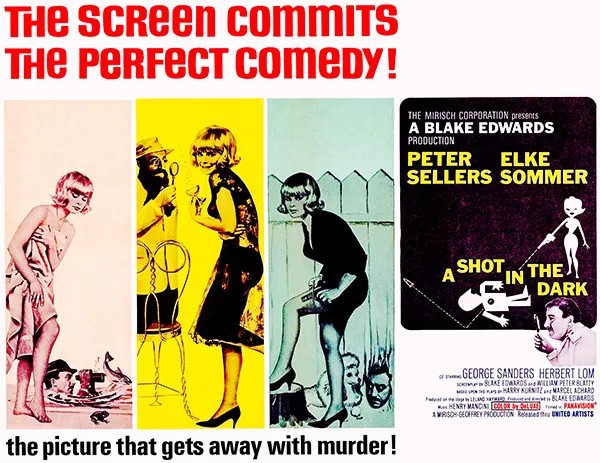

Inspector Clouseau (Peter Sellers) has acquired a more pronounced French accent than since his last incursion in The Pink Panther (1963) but it’s nothing like as excruciatingly hilarious as would be in later episodes. He still falls in love at the drop of a hat though this time the object of his affection is maid Maria (Elke Sommer) who, unfortunately, happens to be the prime murder suspect. She should be in jail but she is constantly released. Clouseau should be sacked for incompetence, but he is constantly reinstated.

The repertory team of his frustrated boss Dreyfus (Herbert Lom) and karate teacher (Burt Kwouk) interrupt proceedings from time to time but don’t really add to the laugh quotient. A bit more effective is the satire on French bureaucracy, a running gag on the need for an official permit, for example, before you could think of selling balloons on the street or trying to earn a buck as a street artist.

I won’t go into the plot since it’s a series of baffling murders and you could argue that Peter Sellers needs neither plot nor love interest. All he needs is an open door beckoning.

I was astonished how often I laughed out loud at something I knew was coming. The minute someone walked through a door you knew Clouseau would be the other side of it waiting to be buffeted. Any open window and he’d be through it and likely as not water would await.

He doesn’t just get tangled up in words but ask him to replace a billiard cue and you’d think billiard cues had declared war on him. He’s forgetful to the point of forgetting to switch off his cigarette lighter and naturally ignores the signs that he’s set his coat on fire.

For those more censorious times, there’s a foray into a nudist colony which is primarily an exercise in the various ways that private parts can be hidden from the camera while suggesting the salacious opposite. Clothed or unclothed you can rely on Clouseau to fall down. The only hilarious scene that doesn’t involve him falling down is when Maria miraculously appears in his office and when an attached key tears a whole in his trousers.

The various twists – Dreyfus is the assassin stalking Clouseau – and the lax French attitude to adultery keep the plot going and when the narrative slackens you can always stick a bomb into the mix.

From the outset, there is plenty opportunity for farce, the wrong people entering the wrong doors, continuous mix-up, plenty occasions for the innocent person to be caught red-handed clutching the murder weapon.

It almost looks as though the two aspects of the picture are clashing. Director Blake Edwards (The Pink Panther) appears to be helming a farce within which Inspector Clouseau is encased. You might think there’s a limit to the number of pratfalls you can stick in a picture, but my answer is “try me”.

With Peter Sellers so dominant, the only way the supporting cast could compete was by over-acting (Herbert Lom) or under-acting (all the rest). Elke Sommer (The Prize, 1963) needs do little more than look winsome.

Written by Edwards and William Peter Blatty (Gunn, 1967) based on the play by Harry Kurnitz.

Occasionally drags but lifted by the genius of Sellers.