Unless you’re a sci-fi buff of a certain vintage, you probably haven’t heard of Murray Leinster who wrote The Wailing Asteroid on which The Terrornauts is based. Which is a shame because he was one of the giants of science fiction of the golden age. Time magazine called him The Dean of Science Fiction.

For a contemporary audience his name is of considerable significance because he invented the concept of the multiverse. In those days it was called a parallel universe or an alternate history but it amounted to the same thing. And he did so nearly a century ago – in 1934 in fact.

He was second only to H.G. Wells in originating science fiction concepts. He was the first, for example, to imagine meeting an alien culture that was as advanced as our own. He explored themes of mutual distrust, mutual assured destruction, and aliens as superior beings. He also invented the idea of the Internet and man-eating plants.

In The Wailing Asteroid, Leinster draws upon many of the ideas he was first to promulgate.

We have alien encounter. We have the fear that as a consequence terror might be brought back to Earth. We have a species that has evolved far beyond human experience.

We have the same kind of instant absorption of knowledge that occurs through the Internet. The little blocks that our hero finds might as well be called Miniature Googles.

You could also argue that what the space explorers discover is akin to The Sentinel that features in 2001: A Space Odyssey, released in 1968. And you could also view the asteroid as a life-affirming alternative to the hovering destructive Death Star of Star Wars filmed a decade later.

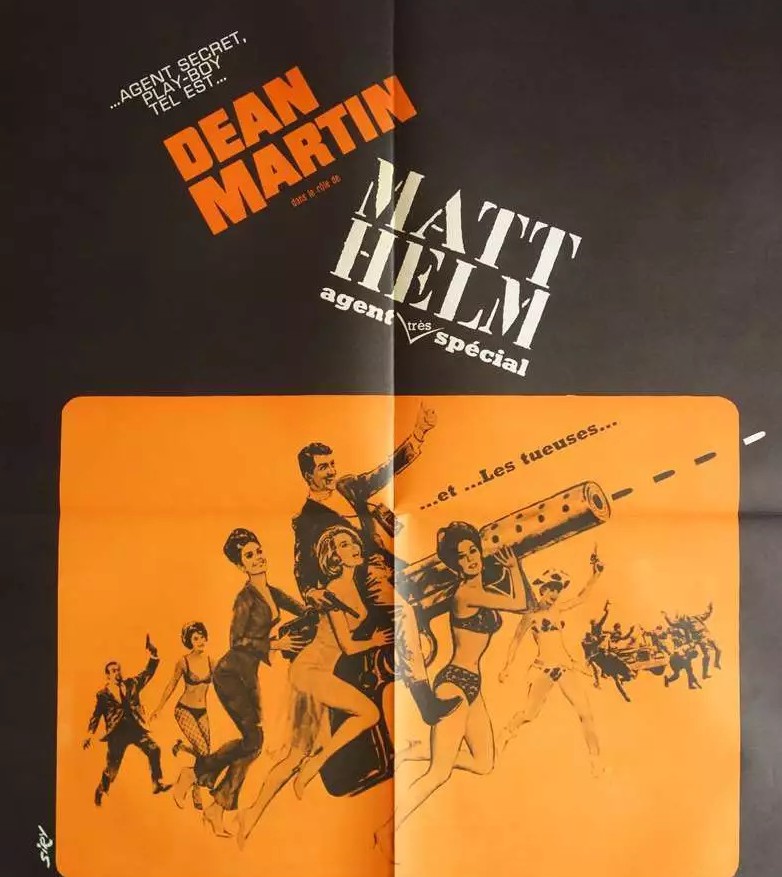

The Terrornauts is a rarity because only a handful of Leinster books were ever filmed. But he was very important to the movies in another way, at the forefront of an invention – front projection – that changed the way movies were made in the 1960s.

At this point, production entity Amicus was as well known for its sci fi output as its horror thanks to Dr Who and the Daleks (1965) and Daleks Invasion Earth 2015 A.D (1966).

So when Embassy Pictures knocked on the door and offered a flat fee of around half a million dollars for a science fiction double bill, Amicus was delighted. Hammer sold its horror pictures as double bills, a complete program more attractive to an exhibitor and more lucrative for a producer than half a program.

Amicus contracted to make The Terronauts and They Came from Beyond Space. They weren’t big enough to have stars under contract, nor the first port of call should a director or star have a pet project that required funding.

Their modus operandi was to trawl through the hundreds of novels published every year, either in pre-publication galley form, or when printed. Max Rosenberg claimed to read 500 books a year. “The basic job of a producer,” explained his partner Milton Subotsky, “is to find properties.” That was how they came across The Wailing Asteroid.

It was occasionally part of the deal in Hollywood that when a studio bought a best-seller, the author was given the opportunity to write the screenplay. But that wasn’t the case here.

Instead, Amicus turned to another science fiction author. John Brunner was as prolific as Leinster. Brunner got the gig because he mixed in the same social circles as Subotsky. Mostly, he wrote conventional space opera and it was only after his experience on The Terrornauts that he acquired a bigger name in science fiction, after winning a Hugo Award in 1969.

The first casualty was the title. The Wailing Asteroid was not as catchy as The Terrornauts. And Brunner had no qualms about scrapping most of the original narrative. He telescoped the time frame. The action in the book takes place over several months, not a couple of days. The book involves multiple countries. Leinster’s novel was set in the United States, but Brunner made the characters British and added the comedy – no tea lady or accountant in the original. And there’s no humor either. He changed the hero’s occupation from design engineer to scientist, and dumped the incipient hesitant romance between Joe and Sandy. But he brings in the notion of scientists hunting for intelligent life in space.

Nor does Leinster’s book involve little green men, robots or human sacrifice. That’s all Brunner’s doing. He turns what was really a concept novel, an exploration of ideas more akin to 2001: A space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes. Brunner shifts it from what if to alien abduction.

Budget shaped the picture. The first four reels are slow and full of dialog because dialog can be shot much quicker and more cheaply than action. Low budgets didn’t bother Amicus. “I defy any other picture making company,” proclaimed Rosenberg, “to turn out that sort of picture with the budget we are under.” He added, “We make pictures for a price and I think we’re better at it than anybody else.”

Amicus had something of a stock company, Freddie Francis, for example, the in-house director, had helmed four pictures, the same number as Peter Cushing headlined. Christopher Lee starred in two, Robert Bloch contributed four scripts and Elizabeth Lutyens scored two pictures. But only Lutyens was retained here.

Amicus handed The Terrornauts to veterans, the majority involved were over 50 years of age. Cinematographer Geoffrey Faithful was 74, author Murray Leinster 71, supporting actor Max Adrian 64, special effects guru Les Bowie 64, director Montgomery Tully 63, composer Elizabeth Lutyens 61.

It would prove the last hurrah for female lead Zena Marshall, Montgomery Tully would bow out later that year after Battle Beneath the Earth and Geoffrey Faithful would only make another two pictures.

The Terrornauts and They Came from Beyond Space were not filmed in October-December 1966 as has been widely reported. Instead, production took place earlier in the year. According to British trade magazine Kine Weekly’s Shooting Now section, The Terrornauts was first to go before the cameras at Twickenham Studios, on June 13 1966 and still featured on its production chart on August 3. Filming on They Came from Beyond Space in the second last week of September continued also at Twickenham until the week of November 3.

Though to some observers the amount spent on The Terrornauts was very little, in fact the £87,000 budget was nearly double the amount spent on City of the Dead and slightly more than The Skull. Admittedly, there were special effects to consider but to offset that the stars came cheaper than the likes of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee.

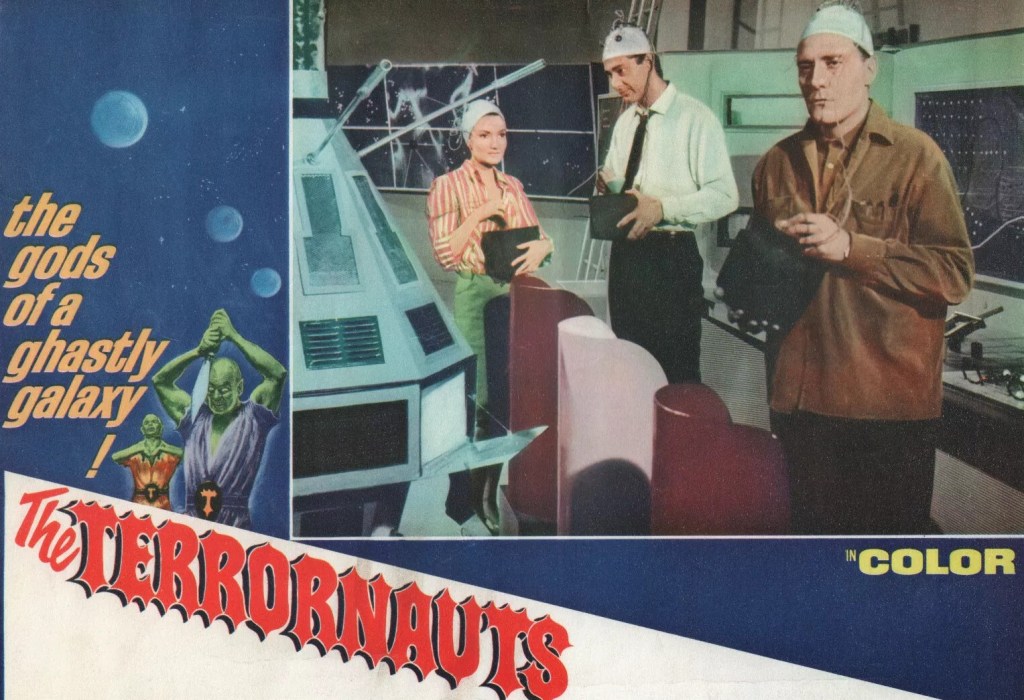

For a time it looked as if Embassy expected The Terrornauts to prove the more popular picture. It ran a one-page advertisement in trade newspaper Variety for The Terrornauts in April 1967 claiming it would be available to rent the following month. The image of Zena Marshall being held down by aliens was accompanied by the tagline – “the virgin sacrifice to the gods of a ghastly galaxy” They didn’t run any adverts for They Came from Beyond Space.

I’m sorry to have to tell you this is a condensed version of the audio commentary by me that accompanies the spanking new DVD released by Vinegar Syndrome – I’m sure you’ll forgive me another small plug – and it’s on special offer.