Laurence Olivier could have played a Nazi long before his celebrated villainous turn in Marathon Man (1976). He was producer-director Stanley Kramer’s first choice to play Chief Judge Dr Ernst Janning. He turned the role down in favor of getting married to actress Joan Plowright. Kramer had already decided an all-star cast was required to attract an audience for the grim picture.

The screenplay was an extended version of Abby Mann’s teleplay that had screened on the ABC in 1959. Although Marty (1955) had transitioned with box office and critical success from television to cinemas, that boom was long over.

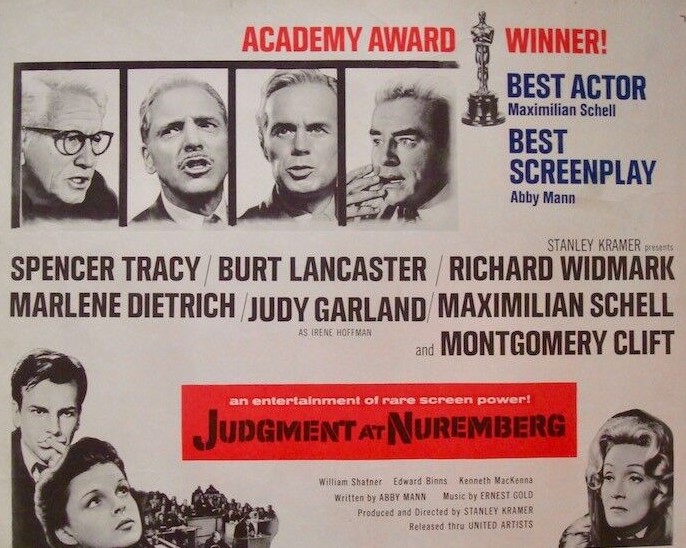

United Artists, with whom Kramer had a multi-picture deal, were not keen. “I did what looked like a compromise to them, but what I had been planning to do anyway. I promised to fill the cast with stars of such magnitude that their presence would almost guarantee the film wouldn’t lose money.”

There were a couple of other obstacles to overcome. A stage version of the teleplay was being planned for London and Paris and Kramer had to take out an injunction against a documentary with a similar title, Verdict at Nuremberg.

Kramer was known as an issues-driven director, his debut Not As a Stranger (1955) tackling the medical profession, The Defiant Ones (1958) racism and in On the Beach (1959) nuclear war. Along with Otto Preminger, he was viewed as a director of “worthy” pictures, not always a recommendation in the eyes of the critics, but as long as the movies made money and attracted Oscar interest likely to remain attractive to studios. Kramer was just about the only producer (High Noon, 1952, and The Caine Mutiny, 1954, on his calling card) who made a successful career-long transition to direction.

With the exception of Olivier, replaced with Oscar-winner Burt Lancaster (Elmer Gantry, 1960) – not incidentally second choice either, the director preferring to have used a German actor – Kramer hired all his first choices. Spencer Tracy, in fact, was the first recruit. After working with him on Inherit the Wind (1960), Kramer got it into his head when considering a picture to ask himself what part there might be for Tracy.

The actor provided “A depth and candor that would make people notice.” Maximilian Schell (Topkapi, 1964) reprised the role he had essayed on television, a man “living in a complicated gray zone.”

Kramer had a reputation for hiring singers and dancers – Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Frank Sinatra – for dramatic roles and he continued in that vein by hiring Judy Garland. It was a difficult decision. He theorized that “the very disorders that made it difficult to work with her fitted perfectly with the role.”

You could have said the same of Montgomery Clift (Freud, 1962), “reduced almost the level of the unsound person he was portraying.” Given the actor’s problems remembering lines, Kramer allowed Clift to basically ad lib, when attacked on the witness stand permitted to reach “for a word in the script” that appeared the correct emotional response to “convey the confusion in the character’s mind.” While Clift did not often adhere to the script, whatever he said worked well enough. Rarely has a director been so sympathetic to a troubled actor. “He needed someone to be terribly kind,” said Kramer, “someone who would consistently bolster his confidence and tell him he was wonderful.

Marlene Dietrich, who had firsthand experience of Nazi Germany at first hand, having fled the country, actually knew the general whose wife she was portraying, which helped to “deepen my understanding of the emotions of Hitler’s victims,” conceded Kramer. Opening up about her experiences and fears allowed Kramer to extend the scope of the character.

While the courtroom where the original trial had taken place was not available for hire – it was in current use – Kramer was permitted to measure and photograph the room to reconstruct it on a soundstage. Only 15 per cent of the movie was shot in Germany.

The experience of filming Inherit the Wind, another courtroom drama, taught Kramer the need to have fluid camerawork since talk and gesture tends to be static. “I learned to move the camera often to achieve a sense of movement for the viewer.”

Abby Mann was required to open up the teleplay, move the action outside the courtroom – scenes in the judge’s accommodation, on the derelict streets, in restaurants – and avoid cinematic claustrophobia and making it a “pious sermon.” “In my opinion,” argued Kramer, “Judgment at Nuremberg conveys a moral not always honoured, then or now, in the world of politics.”

Kramer had a particular method of pre-production. He built all his sets six weeks before filming began. As part of that process, he sat down with his cinematographer and went through the script scene by scene working out the lighting and camera positions. Then he called in the actors and took them through the sets and roughly his shooting thought-process, taking on board any queries and suggestions. Film like this “sort of demanded it be shot in sequence with a single camera,” explained cinematographer Ernest Laszlo (Fantastic Voyage, 1966).

The 360-degree turning of the camera was not as revolutionary as you might imagine – although, according to critics, Michelangelo Antonioni invented it for The Passenger (1975). Laszlo had done if before on The Hitler Gang (1944) for director John Farrow. But this was infinitely more complicated set-up with the revolving camera in constant use to allow Kramer the required fluidity.

“I used two key lights,” said Laszlo. “Shooting this I used one and then as we went round I used the other.” It wasn’t as simple as it sounds, the lights needed to be positioned with mathematical precision so the audience wasn’t aware of any change in the lighting.

“The circling camera saved us photographically,” said Kramer, preventing the picture from seeming “slow and cerebral.” As smooth as it appears on screen it was cumbersome. The entire crew involved had to carry cables and equipment round in a circle. But it permitted Kramer to pick up the judges without cutting to them.

Kramer also used the camera to achieve another transition. As the picture began, German actors spoke in German (with translators offscreen) to show the trial was mostly in German. But for the movie to work, the dialog needed to be in English. “We started the transition scene with Schell addressing the court in German. Laszlo’s camera zoomed in on him, then turned elsewhere, then turned again to Schell so that we were able to switch his speech from German to English in perfect cadence as the camera came in on him the second time. His English picked up from his German so naturally you could almost let it pass without noticing.”

Kramer conceded there might, in fact, be “too much camera movement.” But that was in part dictated by a “very authentic situation, a long courtroom, very wide, and the spacing between the original attorney’s box and the witness box was at least forty feet. That’s a long distance if your try to photograph it.” Also, it wasn’t like a normal Hollywood or American trial, where the lawyers can prowl in front of judge and jury. Here, the attorneys could not move from their box.

“Unless you want to play ping-pong in the cutting room, you have to move the camera…I felt trapped by these three positions – the judges, the attorneys and the witnesses in that big spread. So, the forty feet was compressed to twenty-eight feet. We had to put a lot of light on the far figures to hold the forms in focus,” resulting in the actors “perspiring a lot during these shots.”

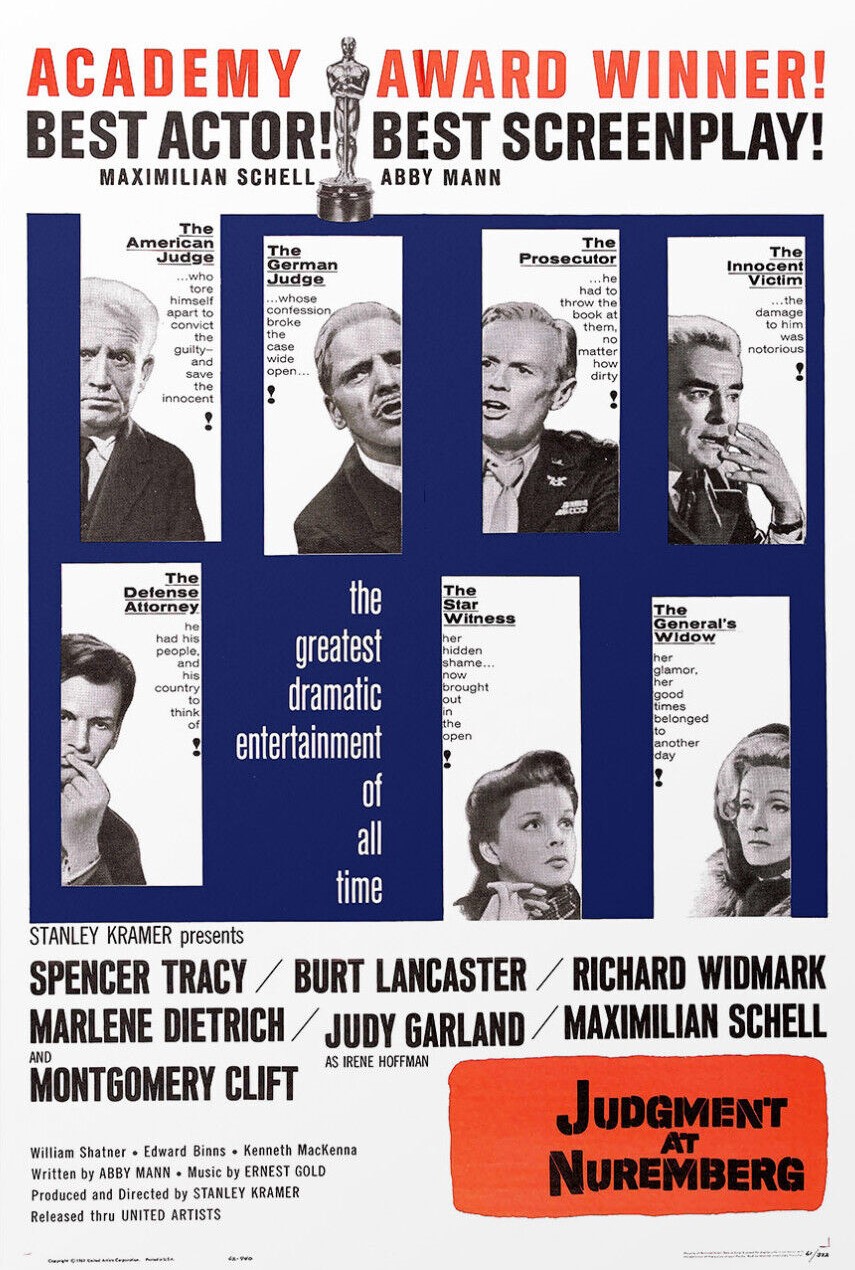

The movie, rolled out as a roadshow, did better than expected, the all-star cast proving a major draw, global box office netting a healthy profit. Schell won the Oscar as did Abby Mann, Kramer was nominated in his dual capacity as producer and director.

SOURCES: Stanley Kramer, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: Life in Hollywood (Harcourt Brace & Company, 1997) p179-197; Donald Spoto, Stanley Kramer Film Maker (Samuel French, 1990)p230-233; “An AFI Seminar with Ernest Laszlo, American Cinematographer, January 1976, p52; “Judgment at Nuremberg Still Slated for Legit,” Box Office, February 3, 1960, p6; “Kramer Gets Injunction,” Box Office, December 11, 1961, p14.