Not cut out for the musicals, comedies, historical adventures (let’s not count The Greatest Story Ever Told, 1965), thrillers, dramas, and spy pictures that dominated that 1960s the western was John Wayne’s default. After his initial battle with lung cancer, he enjoyed an extended period of success in Henry Hathaway’s The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), Howard Hawks’ El Dorado (1967) and Burt Kennedy’s The War Wagon (1967) before diversifying in Vietnam war picture The Green Berets (1968), which he directed and was also a hit, and Andrew V. McLaglen oil drama Hellfighters which did, however, fall short of his high box office standards. So when any big western picture was mooted, it was either Wayne or James Stewart to whom producers first came calling. But when the actor particularly wanted a part, he usually got it.

Charles Portis was a journalist with one modern novel, Norwood published in 1966, to his name when he wrote True Grit, published in 1968, which, unusually for a western, spent 22 weeks in the New York Times bestseller list. The main attraction for a reader was the equally unusual first-person narrator, Mattie Ross, towards the end of her life telling the tale of how as a 14-year-old in Arkansas she sought bloody revenge for the death of her father. The narrative voice was highly individual with colorful phrases, punchy dialogue, and a taut storyline.

Producer Hal Wallis snapped it up for $300,000, beating out Wayne’s Batjac operation. Wallis had been making his own pictures for over two decades, having originally overseen films as varied as swashbuckler Captain Blood (1935) and Casablanca (1942). He also had a western pedigree, having set up John Sturges’ Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), The Sons of Katie Elder and Five Card Stud (1968) with Dean Martin and Robert Mitchum.

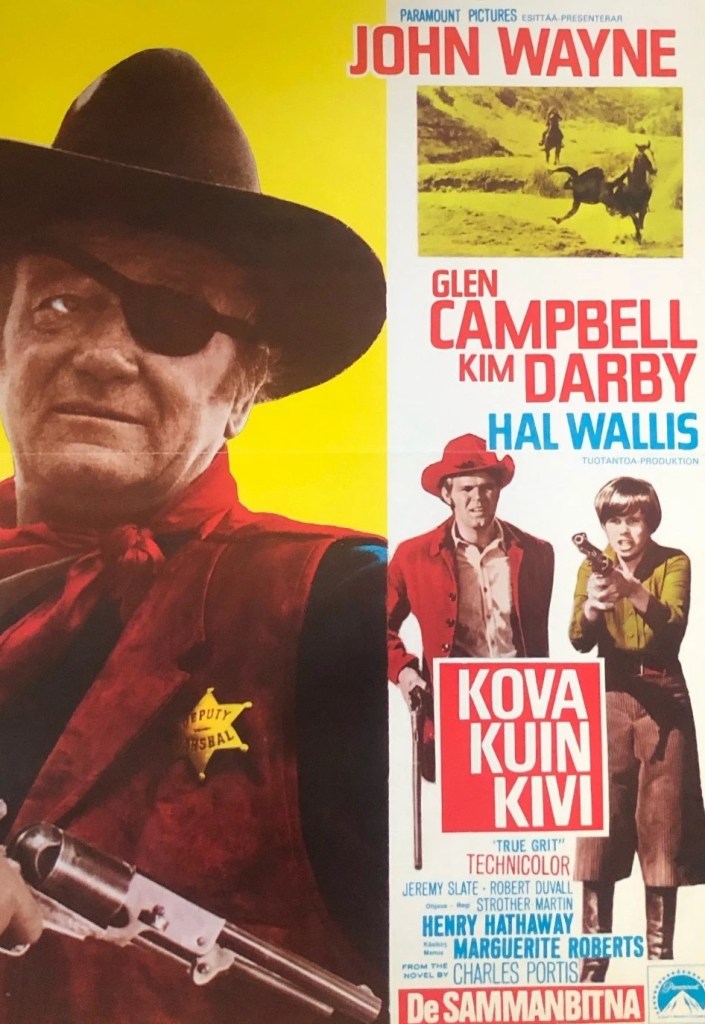

The movie went into speedy production, barely a year from the novel’s publication to the world premiere. From the start Wallis had Wayne in mind for Rooster Cogburn, with Robert Mitchum as back-up. Mia Farrow turned down the role of Mattie Ross when she found out the director was to be Henry Hathaway. Genevieve Bujold turned it down because she didn’t want to work with Wayne. Wayne favored Katharine Ross (The Hellfighters, 1968) or Michele Carey (El Dorado) or his daughter Aissa whom Hathaway ruled out. Sally Field from the television series The Flying Nun was also considered, but the part finally went to 21-year-old Kim Darby.

She had been in the movies since 1963 (an uncredited role in Bye, Bye, Birdie) and, excepting small roles in Bus Riley’s Back in Town (1965) starring Ann-Margret, fourth-billing in both the low-budget The Restless Ones (1965) and Arthur Penn television movie Flesh and Blood (1968), confined to guest roles in routine television series such as The Fugitive, Star Trek, Gunsmoke and Bonanza.

Elvis Presley was touted for the role of Le Boeuf but manager Col. Parker insisted his client receive top billing and the role went to another popular singer Glen Campbell, who had made his movie debut in The Cool Ones (1967). Robert Duvall, filling the boots of Lucky Ned Pepper, was also a refugee from television (The Outer Limits, The Fugitive, Combat) although he had delivered a memorable performance as Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and had risen to third-billing for Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rain People (1969).

Henry Hathaway, a former child actor, had directed 60 movies beginning in 1932. But he had learned about direction at the feet of Josef von Sternberg and Victor Fleming, both hard taskmasters, and only made the move into megging at the third attempt. First of all, he had spent nine months touring India with the idea of making a film in the style of silent documentaries Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925) or Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness (1927). He managed to attract the interest of Irving G. Thalberg but the producer died before funding materialized. Next, Paramount planned to hire him when the studio planned an early 1930s investment in color but got cold feet and the idea was dropped. Finally, when Paramount decided it was going to make its own westerns, rather than buying them in, he was hired to direct Heritage of the Desert (1932) starring Randolph Scott but after six more in that genre – being paid $100 a week for the first two and then $65 a week for the next two after the Depression bit – he hit pay dirt with adventure The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) with Gary Cooper and comedy Go West Young Man (1936) with Mae West.

When Paramount finally embraced three-color Technicolor they chose Hathaway to direct adventure The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1936) starring Sylvia Sidney and Fred MacMurray. “It cannot be merely accidental that he was selected,” commented historian Kingley Canham, arguing that Hathaway had “more than just an aptitude for freshening familiar material through technical resourcefulness.”

And like John Ford he was economical with the camera. “I only shoot what can be used so the producer has no choice…I always cut in the camera, the cutter just has to put the ends together,” he said. Determined to achieve verisimilitude, instead of using studio hand-made locusts for biopic Brigham Young (1940), he travelled to Nevada where had been a big invasion of the insects. Except for this film and The Shepherd of the Hills (1941), starring Wayne, he steered clear of westerns, preferring action and drama. However, he was instrumental in helping Wayne extend his acting style. For Shepherd of the Hills, Hathaway “added new subtleties to the already characteristic western hero persona – the roiling gait and economy of dialog were still very much in evidence but his acting was more mature, more sensitive, and more assured.”

He was called upon to demonstrate further technical mastery in the first of Twentieth Century Fox’s semi-documentary dramas The House on 92nd St (1945) followed by film noir Dark Corner (1946) and Kiss of Death (1947). He made his first western in a decade with Rawhide (1951) toplining Tyrone Power and Susan Hayward and only two other westerns in the 1950s – Garden of Evil (1954), teaming Cooper and Hayward, and Hell to Texas (1958) with Audie Murphy, the twist in this one being the hero rather than the villain subjected to a manhunt. Another technical innovation came with The Desert Fox (1951), where he “did the whole raid before the titles,” the first time any action had been shown prior to the rolling of the opening credits.

He was so impressed with the acting skills of Marilyn Monroe in Niagara (1953) that he purchased Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage intending to team her with Montgomery Clift, but nothing came of the concept. He worked with Wayne again in Legend of the Lost (1957) co-starring Sophia Loren.

But, like Wayne, he returned in triumph to the western in the 1960s, all bar two of his movies in this decade in this genre, the first four of the decade starring Wayne – North to Alaska (1960), How the West Was Won (1962), Circus World (1964) and The Sons of Katie Elder. He had finished up on Five Card Stud when Hal Wallis invited him to direct True Grit. He had only received one Oscar nomination, four decades previously, for The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, and no avant garde French film critic was reassessing his work, but he was known to bring movies in on time, and had his own distinct style if anyone could be bothered looking for it.

Certain themes did reappear, revenge for one, which was central to The Trail of the Lonesome Pine, Kiss of Death, historical adventure The Black Rose (1950), Prince Valiant (1954) with James Mason, The Sons of Katie Elder and Nevada Smith (1966) starring Steve McQueen. He also focused on disruption within the family, and situations where an older man aids an impetuous youngster, both instrumental to True Grit. “He is the only director I know,” observed Kingsley Canham, “to have specialized in films about backwoods and mountains.”

Screenwriter Marguerite Roberts was also old-school, born in 1905, with over 30 screen credits. She sold her first script while working as a secretary at Fox, had her first screen credit in 1933 for Sailor’s Luck. By 1939 she was earning $2,500 a week at MGM and turned out Honky Tonk (1941) with Clark Gable and Lana Turner, Sea of Grass (1946) with Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, Gunga Din remake Soldiers Three (1951) and big-budget historical adventure Ivanhoe (1951) with Robert Taylor and Elizabeth Taylor.

Like Abraham Polonsky she fell out of favor with Hollywood for her left-wing sympathies and was blacklisted for nearly a decade until Daniel Petrie’s The Main Attraction (1962) with Pat Boone and Nancy Kwan, Guy Green’s Diamond Head (1962) with Charlton Heston and Rampage (1963) with Robert Mitchum. She, too, had been working for Hal Wallis on Five Card Stud before receiving the commission to adapt the Portis book.

Roberts was familiar with the Old West, since her father had been a lawman in Colorado. Screenwriter Wendell Mayes, who wrote From Hell to Texas, commented that “Henry Hathaway is very easy for a writer to work with.” “When a screenplay is finished,” said Hathaway, “I go through it and work on it. I worked on True Grit with Marguerite Roberts because there was a great deal of repetition in the book and I eliminated a lot of things.” John Wayne felt Hathaway “never got the creative credit I think is due him…He was sort of a story doctor…a fine, instinctive, creator.”

Her first problem was how to translate the book’s distinctive first-person style onto the screen without the entire movie sounding too archaic and although many speeches were lifted verbatim from the book it was Roberts who established Mattie Ross as an authority figure from the outset by introducer the teenager as her father’s “bookkeeper” and inventing the argument about the type of horses he intended to buy.

The result is an unusual composite of tight storyline, exuberant characterization and wonderful dialog. The movie was filmed mainly in Colorado – Ouray, Owl Creek Pass, Ridgway, Canon City, Montrose, Bishop, and Gunnison – as well as Durango in Mexico and Inyo National Park in California where Hot Creek was used for the outlaw’s cabin and also Sherwin Summit.

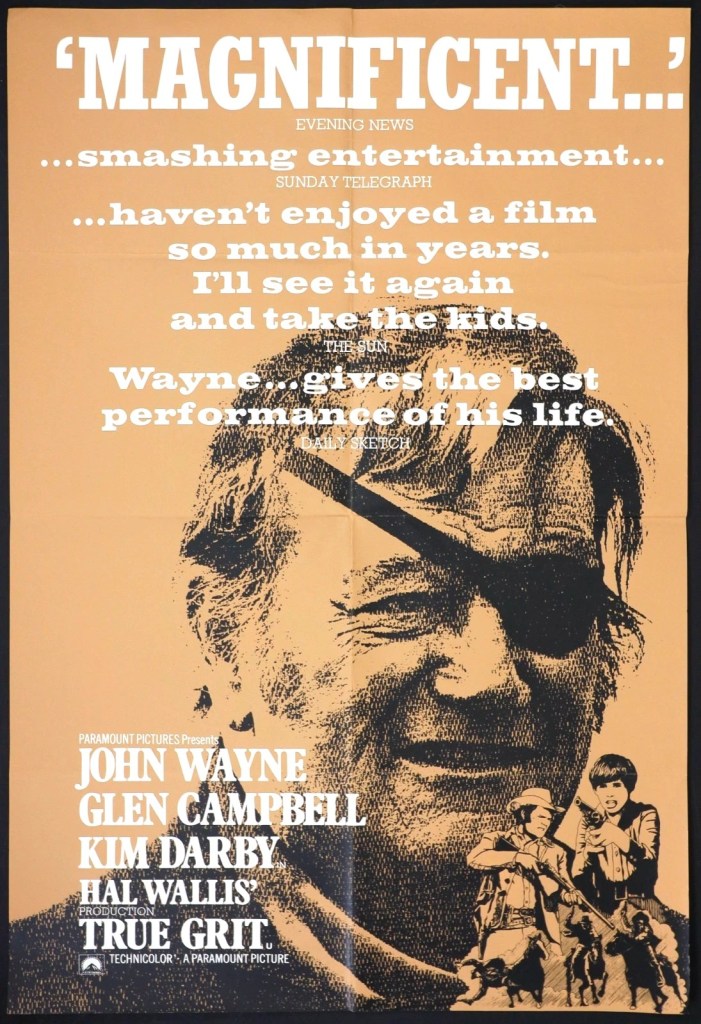

The critics, who had slaughtered The Green Berets the previous year, and been largely indifferent to many of his previous westerns during the 1960s, virtually gave him a standing ovation. Variety called it a “top adventure drama…Wayne towers over everything in the film – the actors, script and even the magnificent Colorado mountains.”

Vincent Canby of the New York Times called it “a triumph…one of the major movies of the year.” The New York Daily News claimed it was “John Wayne’s finest moment.” The New York Post came closest to defining its appeal: “Few westerns will come along this or any other year that can be as fully enjoyed by as many people of varying ages and sex.” Vernon Scott of United Press was not alone in predicting “Wayne should win the Oscar.”

Joyce Haber of the Los Angeles Times said, “come Oscar time Wayne will be a leading contender.” Norma Lee Browning of the Chicago Tribune informed readers that “there’s already talk that he may, at long last, get an Oscar nomination.” Charles McHarry of the New York Daily News held the same view. Time opined “a flawless portrait of a flawed man.” International Motion Picture Exhibitor found it “the perfect vehicle for Henry Hathaway’s directorial style. He approached the simple western story in the most straightforward manner…garnished it with a delightful humor that springs right out of the vagaries of the homespun characters…and giving it a rhythm that carries the viewer along despite its lengthy running time.”

Allen Eyles in Focus on Film summed up the film’s appeal: “That True Grit could end up being the best western of the year is a tribute to old Hollywood – to a producer, director, star, cameraman and others who’ve been at the top of the film business for more than three decades. Their solid, unpretentious professionalism enables them to meet the challenge of filming a first-rate novel with pleasing assurance and directness…it is far superior to…the poorly-shaped but occasionally striking The Wild Bunch from Peckinpah…(it) is not innovatory in style but the details are communicated with a freshness that is appealing.”

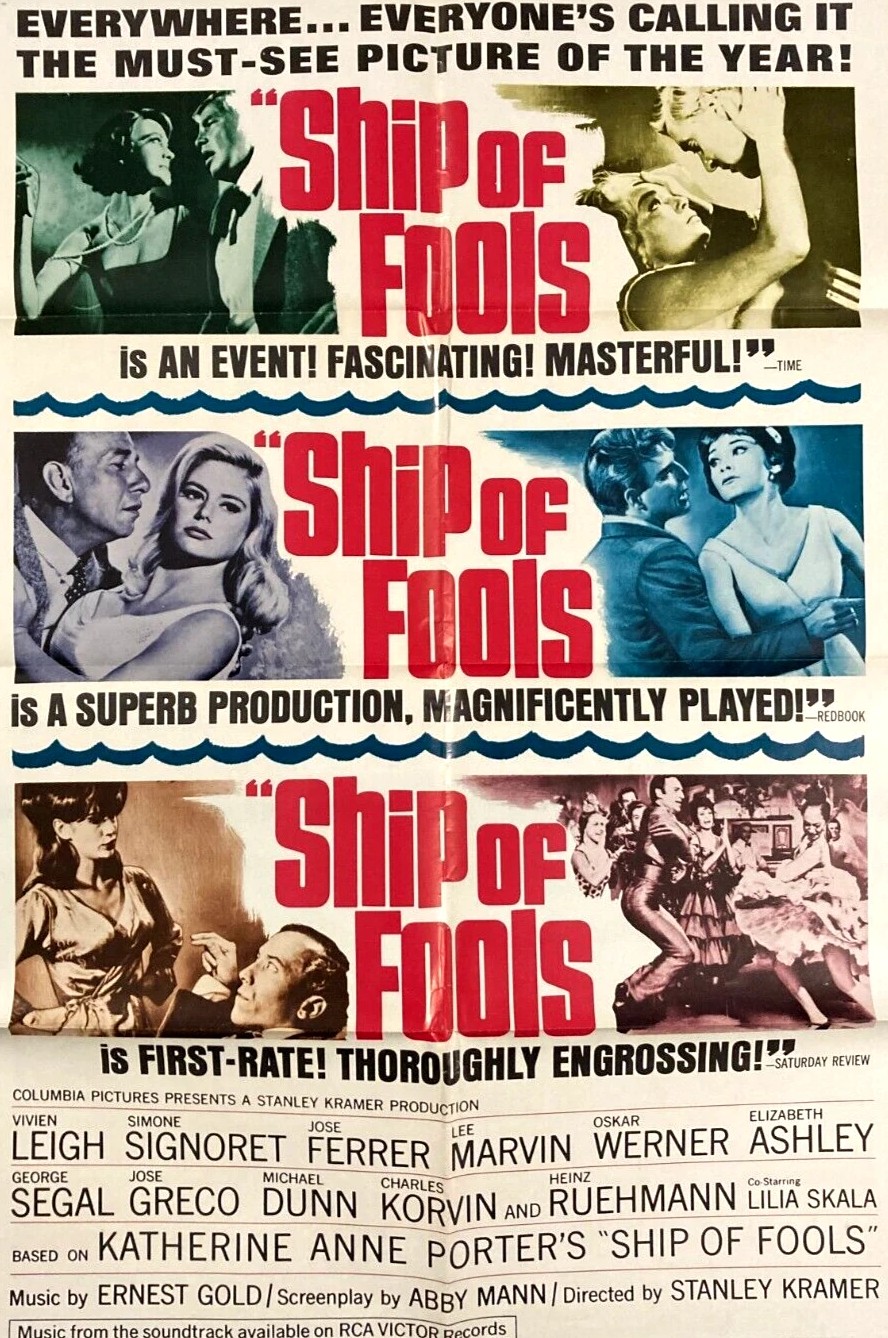

Unusually, for a film of the period, the movie repeated a single image in all of its advertising, Wayne’s face dominating the composition, with below him Mattie Ross standing gun in hand and Glen Campbell behind him. That Campbell sang the title song over the credits led to the release of a record, and there was a New American Library book tie-in. Ancillary promotional items included a t-shirt embellished with the words “This Man Has True Grit,” and buttons announcing “I Have True Grit” and, alternatively, “Give Me a Man with True Grit.” Stetson created a special hat called “The Duke,” with a special one costing $1,500 to be presented to Johnny Carson on his show, with an advertising campaign that included Playboy and Esquire while Aramis created a special line of “Grit Soap.”

Time magazine had raised expectations for the picture by putting John Wayne on the front cover, on August 8, although this was in part retaliation to Life’s joint cover story on Wayne and Dustin Hoffman which ran in the Jul 11 issue, and Paramount took a gamble opening it in New York at the Radio City Music Hall, partly a ploy to boost European revenues, the first western to be so honored, although the theater covered itself by claiming the movie was an “outdoor adventure” rather than a western per se. The picture broke all sorts of records there and went on to conquer America, shattering Dallas records, for example, and then helped along by the Time cover story. For a few months it looked set to become the best performing western of all time, but was soon overtaken by the release of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Even so, it took $11.5 million in rentals to finish sixth in the annual chart. It was reissued after Wayne’s Oscar triumph the following year in an unlikely double bill with Oscar-nominated The Sterile Cuckoo and grossed $3.7 million in the twelve days. But Paramount, trying to offset calamitous losses, prematurely sold off the western to television so its reissue value was sharply curtailed.

SOURCE: Brian Hannan, The Gunslingers of ’69: Western Movies’ Greatest Year, (McFarland, 2019).