I was riveted. This is one of the most extraordinary films I have ever seen. Highly under-rated and largely dismissed for not conforming to audience expectation that horror pictures should involve full moons, castles, darkness, fog, costumes, nubile females exposing cleavage, graveyards, a male leading character, shocks to make a viewer gasp, and the current trend for full-on gore. So if that’s what you’re looking for, give this a miss. Even arthouse critics, spoiled by striking pictures by the Italian triumvirate of Fellini, Visconti and Antonioni, were equally scornful. For the most part this takes place in broad daylight and set in an impoverished town in the Italian mountains, so primitive farmers till the soil with horse and plough and water is collected in buckets from the river.

One of the most striking aspects of the picture is that it creates its own unique universe. The townspeople are both highly religious and deeply superstitious, every traditional Catholic ceremony matched by old-fashioned ritual. Even some of the formal traditions seem steeped in ancient belief, sinners marching up a steep hill being scourged or carrying a heavy rock, in a convent the tree of a suicide covered in barbed wire. Less conformist notions include a wedding night rite involving shoving a scythe under the bed to cut short Death’s legs with the bedspread covered in grapes to soak up evil and discord arranged in the form of a cross to act as bait for bad thoughts and poison them before they can cause the couple harm. When the people run through the town brandishing torches it is not, as would be genre tradition, to set fire to a castle but to vanquish evil from the air.

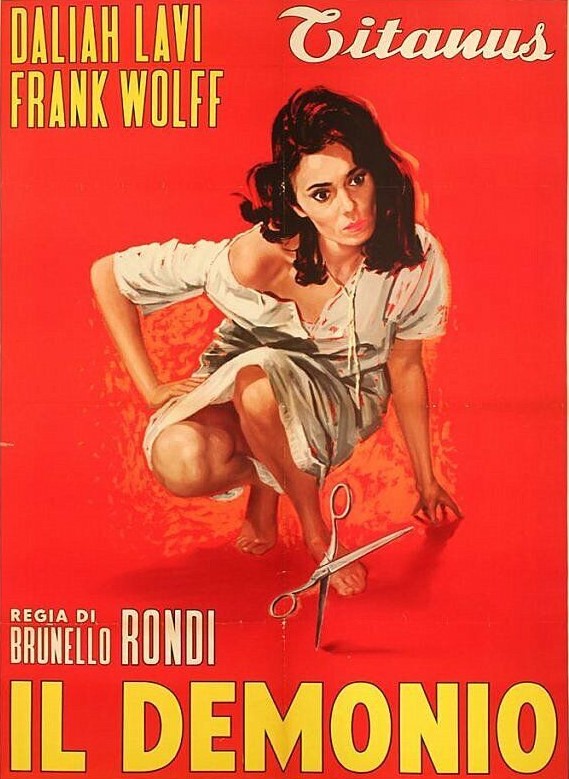

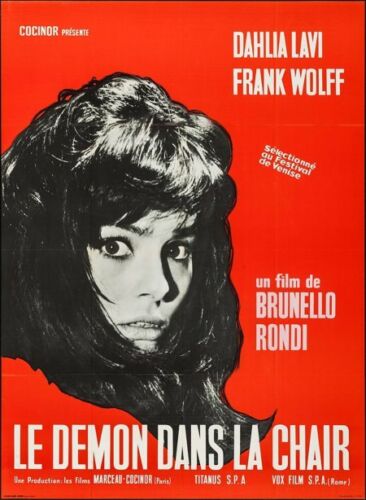

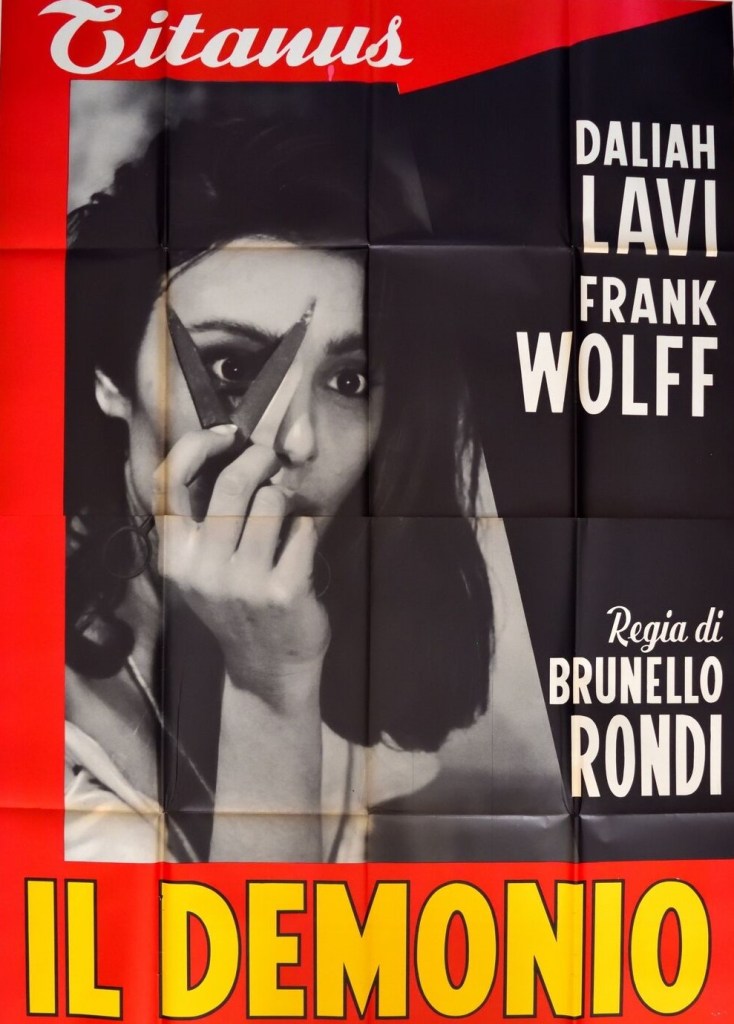

It is filmed in austere black-and-white. In the Hollywood Golden Era of black-and-white movies lighting and make-up transformed heroines, rich costumes enhanced background. Here, if the heroine is wearing make-up it’s not obvious and the only clothes worth mentioning are a priest’s robes or a plain wedding dress. Otherwise the most arresting feature is the stark brightness against which the black-dressed figure of the heroine Puri (Daliah Lavi) scuttles about.

And although there are no jump-out-of-your-seat shocks, there are moments that will linger on in your mind, not least the heroine enduring a vicious extended beating from her father, an exorcism that turns into rape and the sight, Exorcist-fans take note, of a spider-walk, the young woman’s torso thrust up high on elongated arms and legs. Virtually the entire success of the picture relies on atmosphere and in places it is exquisitely subtle, the audience only realizes she has been raped by the look on her face.

The picture opens with a dialog-free scene of stunning audacity, foreshadowing the idea from the start that image is everything. Puri pierces her chest with a needle, cuts off a chunk of her hair to mop up the blood, throws the hair into the oven and rams the crisp remains into a loaf of bread. Not to be consumed as you might imagine, but as a tool of transport. Shortly after, having failed to seduce Antonio (Frank Wolff), she tricks him into drinking wine infused with the ashes of her bloodied hair, bewitching him, so she believes, to abandon his betrothed. In an echo of a Catholic sacrament she shouts, “You have drunk my blood and now you will love me, whether you want to or not.”

The next morning when collecting water at the river she has a conversation with a boy Salvatore only to discover he has just died, his death blamed on her because his last words were a request for water, which she is judged to have denied him. She is beaten by women. She is feared by everyone in the village, her family tainted with the same brush, wooden crosses nailed to their door. She is not a ghostly figure, flitting in and out of the townspeople’s lives, an apparition tending towards the invisible, but fully formed, highly visible in her black dress and anguished expression, doomed by often vengeful action and forceful word.

Much of the film involves Puri being beaten or chased or captured, at one point trussed up like a hog. Attempts to exorcise her, whether pagan or Catholic, focus on getting the demon to speak his name. The ritual performed by heathen priest Guiseppe involves blowing on a mirror before taking on sexual aspects which culminate in rape. The Catholic version in a church in front of her family is primarily, as it would be in The Exorcist, a duel between the priest and whatever possesses her.

Movie producers took one look at the beauty of Palestinian-born Daliah Lavi (Blazing Sand, 1960) and thought she would be put to better use in bigger-budgeted pictures made in color that took full advantage of her face and figure and that stuck her in a series of hardly momentous movies such as The Silencers (1966) and Some Girls Do (1969). They should be ashamed of themselves for ignoring her astonishing acting ability. And much as I have enjoyed such films, I doubt if I could watch them again without thinking what a waste of a glorious talent. This is without doubt a tour de force, as she alternatively resists possession and adores the being who has taken hold of her mind. She dominates the screen.

The rest of the mostly male cast are dimmed in comparison, as if overawed by the power of her personality. Future spaghetti western veteran Frank Wolff (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1968) comes off best. Director Brunello Rondi (Run, Psycho, Run, 1968) is better known as a screenwriter for Federico Felllini. He made few films, none matching this in scope or imagination, perhaps as a result of the picture not receiving the praise it deserved. Even now it does not have a single critical review on Rotten Tomatoes.

One other point: you may have noticed that in general the proclivities of male horror characters are never in need of psychological explanation. Nobody considers that the Wolfman must have suffered from childhood trauma or that a vampire drinks blood because he was a rejected suitor. Strangely enough, as would be the case in The Exorcist and other instances of female possession, psychiatry is usually the first port of call and here all reviews I have read implicitly see Puri’s actions as based on sexual inhibition and rejection by Antonio.