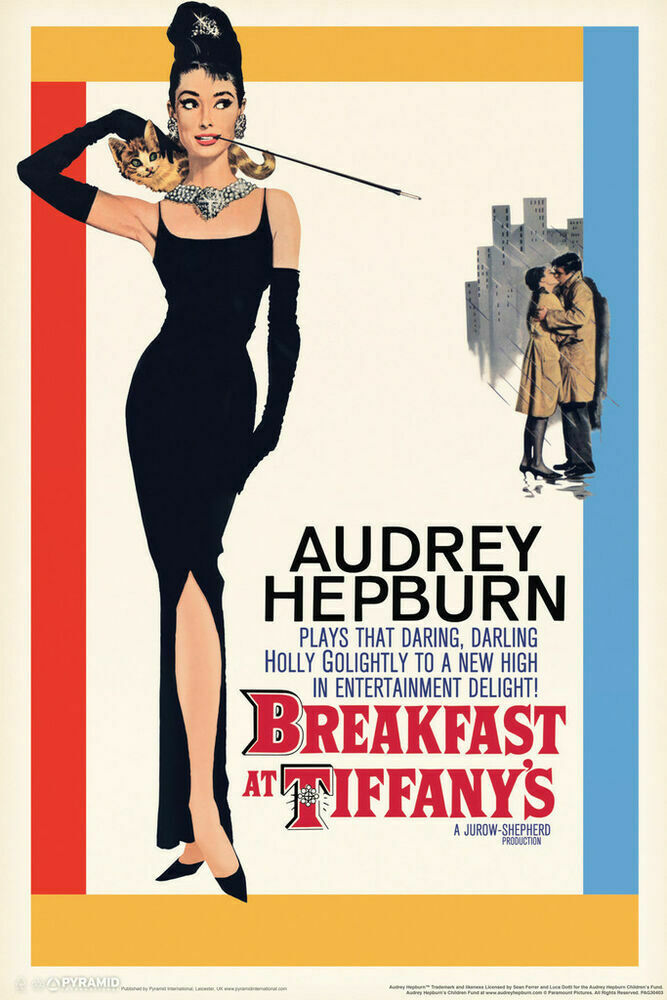

Reassessment sixty years on – and on the big screen, too – presents a darker picture bursting to get out of the confines of Hollywood gloss. Holly Golightly (Audrey Hepburn) is one of the most iconic characters ever to hit the screen. Her little black dress, hats, English drawl and elongated cigarette often get in the way of accepting the character within, the former hillbilly wild child who refuses to be owned or caged, her demand for independence constrained by her desire to marry into wealth for the supposed freedom that will bring, demands which clearly place a strain on her mental health.

Although only hinted at then, and more obvious now, she is willing to sell her body in a bid to save her soul. Paul Varjak (George Peppard), a gigolo, being kept, in some style I should add, with a walk-in wardrobe full of suits, by the nameless wealthy married woman Emily (Patricia Neal), is her male equivalent, a published writer whose promise does not pay the bills. The constructs both have created to hide from the realities of life are soon exposed.

There is much to adore here, not least Golightly’s ravishing outfits, her kookiness and endearing haplessness faced with an ordinary chore such as cooking, and a central section, where the couple try to buy something at Tiffanys on a budget of $10, introduce Holly to New York public library and boost items from a dime store, which fits neatly into the rom-com tradition.

Golightly’s income, which she can scarcely manage given her extravagant fashion expense, depends on a weekly $100 for delivering coded messages to gangster Sally in Sing Sing prison, and taking $50 for powder room expenses from every male who takes her out to dinner, not to mention the various sundries for which her wide range of companions will foot the bill.

Her sophisticated veneer fails to convince those whom she most needs to convince. Agent O.J. Berman (Martin Balsam) recognizes her as a phoney while potential marriage targets like Rusty Trawler (Stanley Adams) and Jose (Jose da Silva Pereira) either look elsewhere or see danger in association.

The appearance of her former husband Doc (Buddy Ebsen) casts light on a grim past, married at fourteen, expected to look after an existing family and her brother, and underscores the legend of her transformation. But the “mean reds” from which she suffers seem like ongoing depression, as life stubbornly refuses to conform to her dreams. Her inability to adopt to normality is dressed up as an early form of feminism, independence at its core, at a time when the vast bulk of women were dependent on men for financial and emotional security. Her strategy to gain such independence is of course dependent on duping independent unsuitable men into funding her lifestyle.

Of course, you could not get away with a film that concentrated on the coarser elements of her existence and few moviegoers would queue up for such a cinematic experience so it is a tribute to the skill of director Blake Edwards (Operation Petticoat, 1959), at that time primarily known for comedy, to find a way into the Truman Capote bestseller, adapted for the screen by George Axelrod (The Seven Year Itch, 1955), that does not compromise the material just to impose a Hollywood gloss. In other hands, the darker aspects of her relationships might have been completely extinguished in the pursuit of a fabulous character who wears fabulous clothes.

Audrey Hepburn (Two for the Road, 1967) is sensational in the role, truly captivating, endearing and fragile in equal measure, an extrovert suffering from self-doubt, but with manipulation a specialty, her inspired quirks lighting up the screen as much as the Givenchy little black dress. It’s her pivotal role of the decade, her characters thereafter splitting into the two sides of her Golightly persona, kooks with a bent for fashion, or conflicted women dealing with inner turmoil.

It’s a shame to say that, in making his movie debut, George Peppard probably pulled off his best performance, before he succumbed to the surliness that often appeared core to his acting. And there were some fine cameos. Buddy Ebsen revived his career and went on to become a television icon in The Beverley Hillbillies. The same held true for Patricia Neal in her first film in four years, paving the way for an Oscar-winning turn in Hud (1963). Martin Balsam (Psycho, 1960) produced another memorable character while John McGiver (Midnight Cowboy, 1969) possibly stole the supporting cast show with his turn as the Tiffany’s salesman.

On the downside, however, was the racist slant. Never mind that Mickey Rooney was a terrible choice to play a Japanese neighbor, his performance was an insult to the Japanese, the worst kind of stereotype.

The other plus of course was the theme song, “Moon River,” by Henry Mancini and Johnny mercer, which has become a classic, and in the film representing the wistful yearning elements of her character.