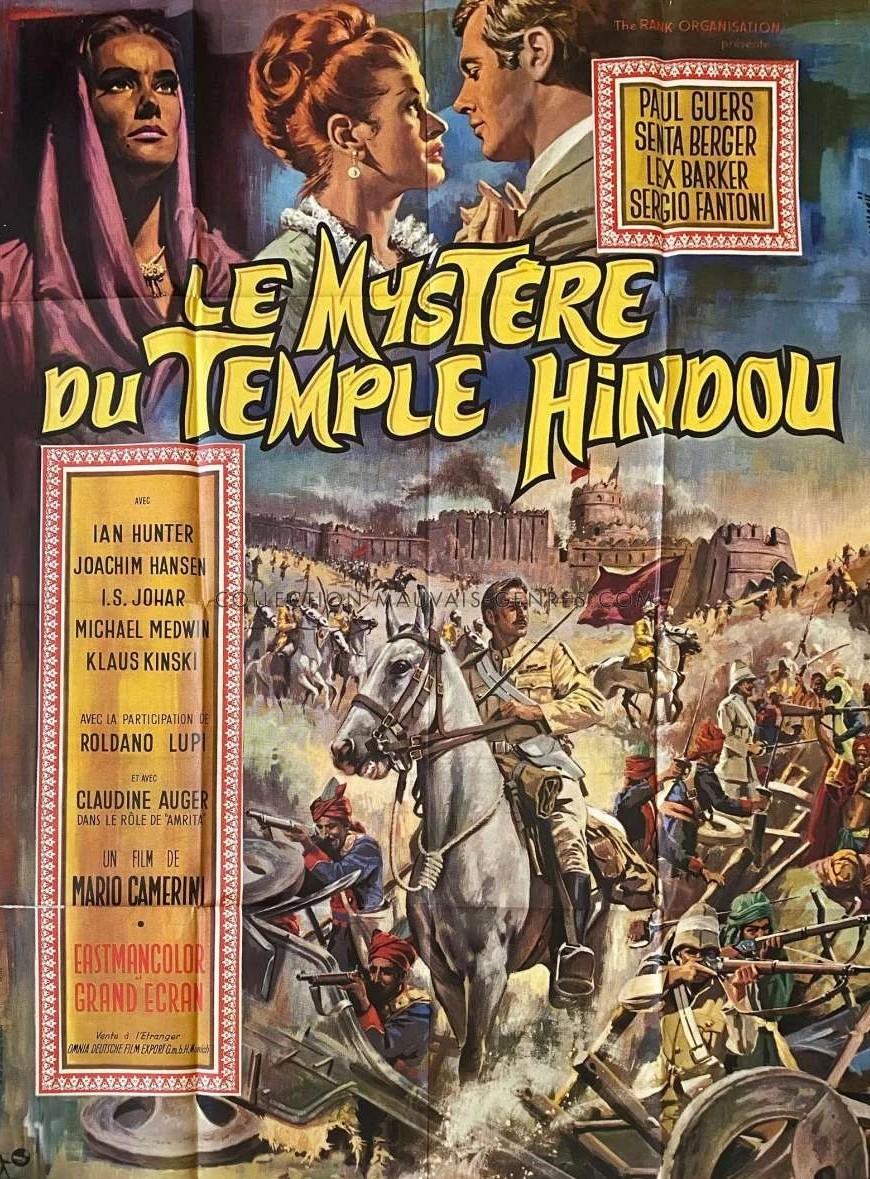

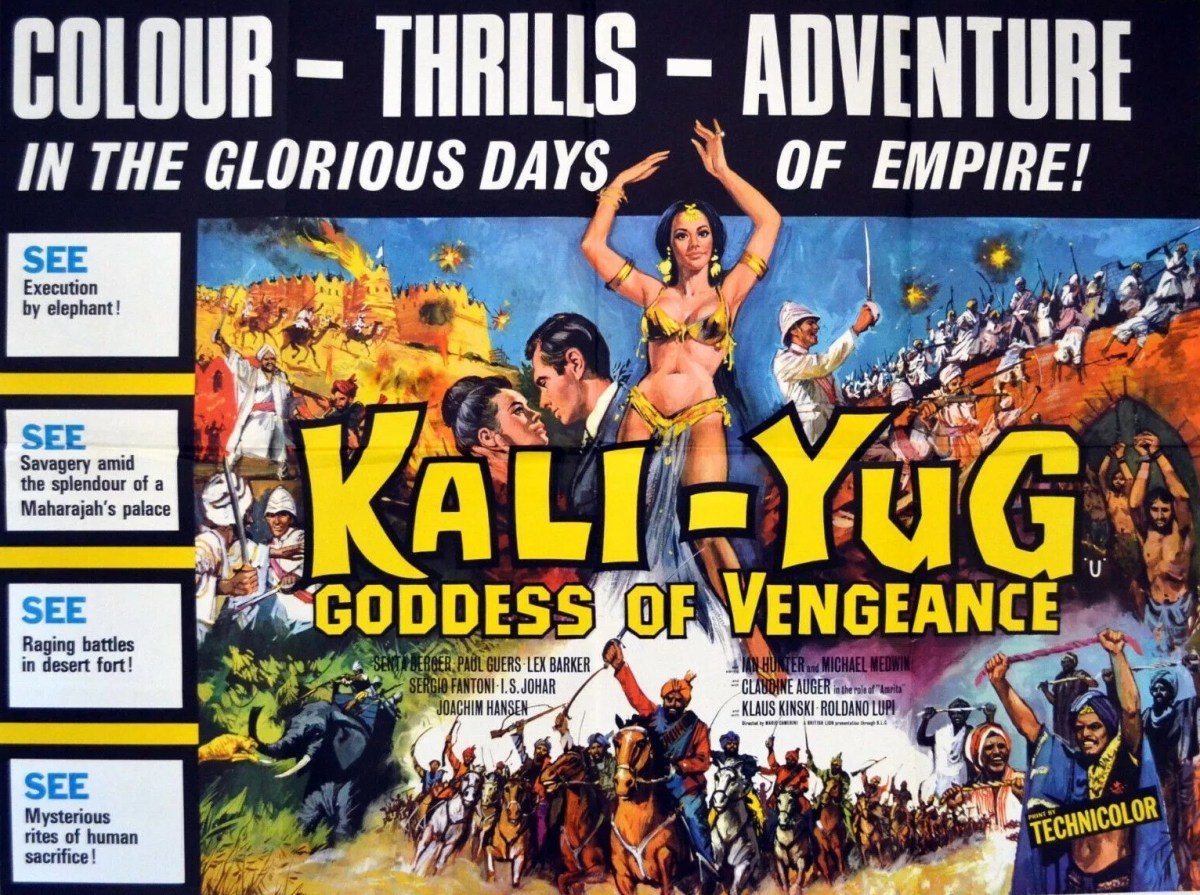

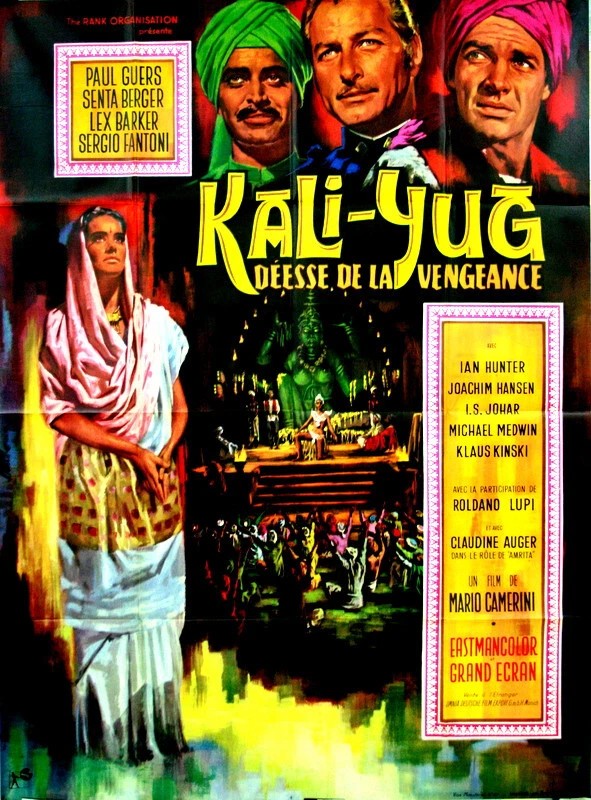

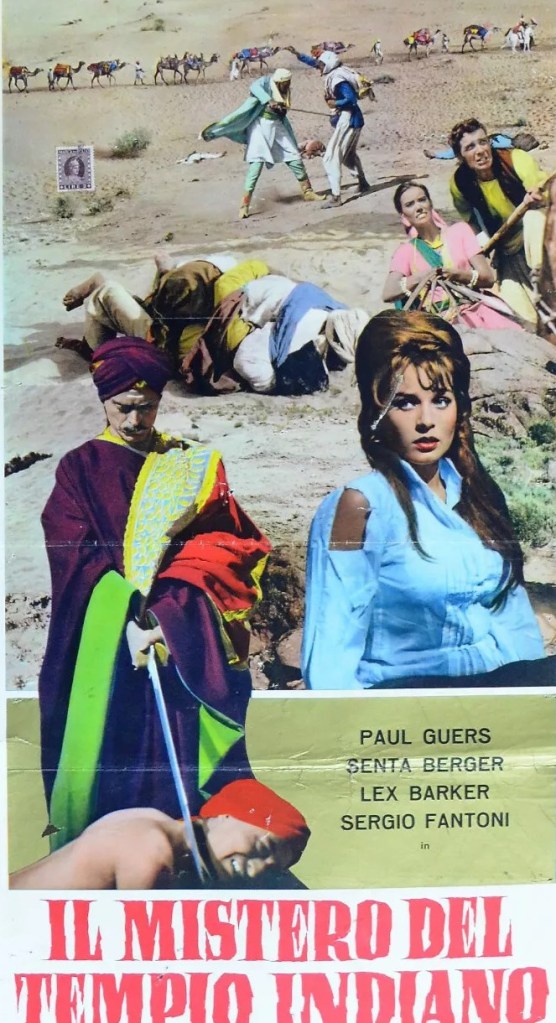

Earnest students of the Senta Berger Syllabus may be somewhat disappointed, I’m afraid. This turns out to be an epic movie – in two parts – but even with a three-hour running time there’s hardly any space for the second-billed Ms Berger. Instead it’s the second female lead Claudine Auger who leads the way.

And as if it’s forerunner of the contemporary serial there’s a (longish) recap of part one, though this time recounted as if it’s nightmare into which our hero Englishman Dr Simon Palmer (Paul Guers) has unwittingly tumbled. He’s not, as I had imagined from the end of episode one, free. He’s still imprisoned by the Maharajah (Roldano Lupi) along with servant Gopal (I.S. Johar) although he has begun to deduce that all is not what it seems and that an insurrection may be on the cards under the guise of a revival of the cult devoted to the Goddess Kali.

And when exotic dancer (in the old sense, not the contemporary) Amrita (Claudine Auger) fails to convince the Maharajah of Palmer’s innocence she organizes his escape via the old snake in the basket trick. But this is not altogether from altruism. The good doctor is whisked away to treat three children who have caught diphtheria, unaware one of them is the Maharajah’s grandson, kidnapped (in Part One) by the Kali cult of which she is a key participant. However, she is beginning to thaw in her attitude to the Englishman and wonder why the goddess Kali, to whom she is bound by oath, is so determined to kill such a good man.

They end up in the caravanserai of cult leader Siddhu (Klaus Kinski), but Amrita, who’s undergoing a crisis of faith, organizes their escape, along with the boy. She has betrayed her calling – her father was a priest of Kali – in order to save Palmer. They manage to evade the pursuing pack of thugs. When the road back to Hasnabad is blocked, they decide to make for the enemy lair, an abandoned fort in the desert turned into the rebel stronghold, on the basis of hiding in plain sight, nobody expecting them to head in that direction.

Meanwhile, on his way to the fort, the Prince (Sergio Fantoni), now showing his true colors, has kidnapped Catherine Talbot (Senta Berger), planning to trade her for the Maharajah’s grandson who is “absolutely essential” to his plans. Theoretically, there’s nothing her husband can do to save her. According to the Treaty of Delhi, British forces cannot cross state lines. However, Talbot (Ian Hunter) reckons that, as he’s technically a civilian, that rule doesn’t apply to him and Major Ford (Lex Barker) comes up with a similar ploy, explaining that he’s given his soldiers ten days’ leave leave and to his “great surprise” they all decided to spend it in the fort.

Meanwhile, to complicate matters, Amrita decides Palmer is so far from being a bad guy that he’s worth kissing. But that romance is nipped in the bud when Palmer spots Catherine being dragged along in the Prince’s caravanserai and decides to rescue her. Furious at discovering that Catherine takes precedence in Talbot’s romantic scheme, and correctly assuming she’s going to be dumped, she knocks him out and turns him and the boy over to the Prince. While the child is acclaimed as the “sacred prince” and figurehead of the revolution, Palmer is to be sacrificed to the goddess. While waiting for that, he’s chained up next to Catherine.

So now you know we’re going to be perming two from four. This doesn’t feel like it’s heading in the bold direction of everyone coming out of it bitterly disappointed on the romance front.

And so it transpires. Talbot the Resident, more courageous than you might expect, dies in the attack on the fort while Amrita is killed trying to protect Palmer. Although for a time it’s a close run thing, what with the attackers outnumbered and running out of ammunition, luckily they are saved by the arrival of the Maharajah’s army. And with Amrita and the Resident out of the way, the path is clear for the old flames to renew their romance though that’s implied rather than shown.

No tigers or elephants this time round, wildlife limited to a dancing bear and a performing monkey.

Hardly a story that requires such an epic scale and I’m wondering if it was so long they had to edit it into two parts or whether it was filmed in the fashion of The Three Musketeers (1973)/The Four Musketeers (1974) with both sections shot at the same time. I’m not sure how audiences reacted. From what I can gather moviegoers in some parts of the world only saw part one while others were limited to part two, that recap helping make the narrative comprehensible.

Senta Berger (Cast a Giant Shadow, 1966) completists will come away disappointed given how restricted her role is. But she does bring the necessary emotions of remorse and humiliation to the part. Claudine Auger (Thunderball, 1965) has the better role, femme fatale, conspirator, lovestruck, spurned, and at various points leaping into action. Lex Barker (24 Hours to Kill, 1965) looks as though he’s signed up for a role requiring a hero only to be not called upon to act as one. Fans of Klaus Kinski (Five Golden Dragons, 1967) will be similarly disappointed.

Paul Guers (The Magnificent Cuckold, 1964) looks thoroughly puzzled throughout although he gives plenty lectures on general fairness while Sergio Fantoni (Esther and the King, 1960) concentrates on how unfair the British – considered the exponents of fair play – actually are.

Given it was made outside the British studio system, the producers are free to be quite critical of the British in India and there are pointed remarks about “dirty little Hindus” and about how the British treat even the Indian elite with obvious contempt. In order to retain autonomy, the Maharajah has been forced into becoming a merchant to save his people from starvation thanks to the amount he is taxed. And the story pivots on the lack of medication supplied by the British to natives. The Resident hasn’t even bothered to reply to Palmer’s letters begging for medicine.

The picture is even-handed in its depiction of British rule. Film makers were always in a dichotomy about rebels. Sometimes they were the good guys rising up against despicable authority, sometimes they were the bad guys disrupting a just system. Here, since the rebels belong to a vicious cult that would kill regardless of cause, they come off as the villains of the piece.

Mario Camerini (Ulysses, 1954) directs without the budget to make the most of the story, the battles or the location. Along with writing partners Leonardo Benvenuti and Piero De Bernardi (Marriage Italian Style, 1964) and Guy Elmes (Submarine X-1, 1968), he had a hand in the script adapted from the Robert Westerby novel.

Not complex enough to be an epic, and not enough of Senta Berger to satisfy your reviewer, still interesting enough if you are thinking of seeking it out. Good prints of both parts are on YouTube.