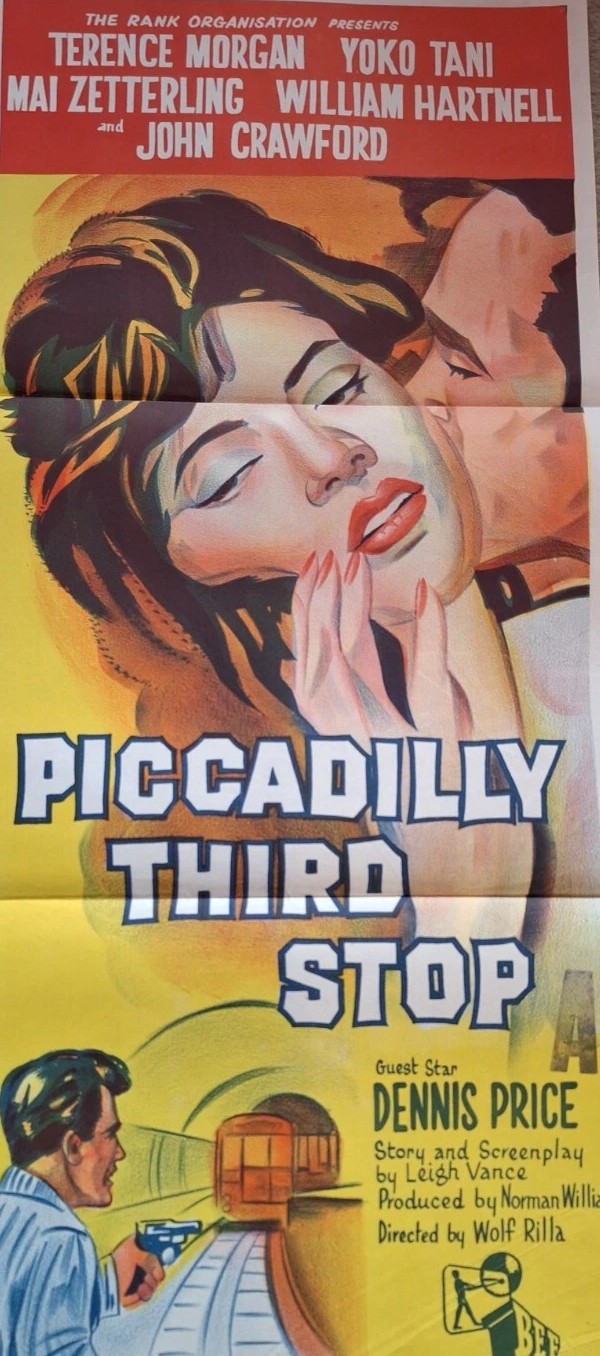

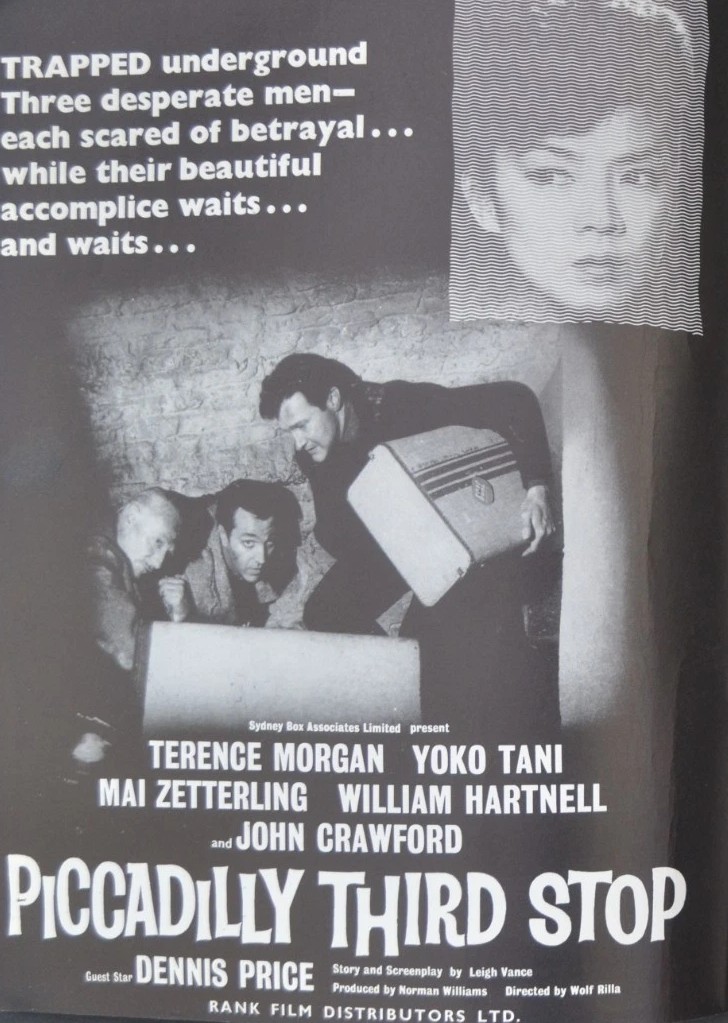

Well-worked full length British thriller that goes against the grain of presenting sympathetic hoods in the vein of Ocean’s Eleven or The League of Gentlemen both out the same year in which audiences largely align with the gangsters in part because they come across as charming and in part because their aims appear thoroughly reasonable.

Unlike the shorter efforts under the Renown umbrella this has time to develop several narrative strands, with deceit the main motivation, and spends a goodly time on the mechanics of robbery, the planning, the percentage split accorded each member, and the heist itself, which is an arduous one, involving digging through a brick wall.

Dominic (Terence Morgan) isn’t exactly a petty thief not when he can dress himself up to the nines, infiltrate a society wedding and make off with an expensive piece of jewellery, which he hides in an unusually clever fashion. But working on his own account is far more lucrative than being an employee in a watch-smuggling ring run by Joe Preedy (John Crawford) who has a classy wife Christine (Mai Zetterling) and life and has so much dough lying around that he’s easy pickings for Dominic who has a side hustle bring dupes to the gambling tables of the pukka Edward (Dennis Price).

Dominic happens to be bedding Christine but that still leaves him time to romance Fina (Yoko Tani), daughter of an ambassador, who casually reveals the embassy safe contains £100,000. She’s so helplessly in love she falls for his tale of them running off together and becomes an accomplice.

With the assistance of Edward, Dominic snookers Joe into supplying the readies to pay for the robbery set-up costs, the tools, gelignite etc. The plan involves digging a hole through the tunnels of the London Underground into the basement of the embassy.

Joe’s share of the spoils will hardly cover his debts so he’s intent on making off with the full amount. As it happens, Dominic has precisely the same idea. Christine is roped in, unknown to her husband, to act as getaway driver.

There’s a hefty dose of characterization unusual in these movies, more than just information dumps about characters. Dominic could easily fund the caper with the cash he would get from selling the stolen diamond, but he holds out for a larger amount from a fence. Joe should easily be able to afford the money, but he’s in dire financial straits because he lost a packet at the gambling tables and his own astuteness in ferreting away all he owns in his wife’s name. That puts his gains well beyond the long arm of the law but leaves him illiquid (I guess is the technical term) and he has to beg Christine to pawn her mink coats.

She’s a smooth operator, an amateur artist, happily living off Joe’s nefarious activities while running around with Dominic and planning to run away with him at robbery end. Joe’s desperate to be seen as a major player, hence his attendance at the casino, and kicking off when he doesn’t get his way, and raging against all the toffs born with a silver spoon in their mouths.

Two of the subsidiary characters are interesting studies. Safecracker the Colonel (William Hartnell) has too much of an eye for the pretty lady and too great a capacity for alcohol, but he’s been careful with his loot, spreading it around in various investments, very secure in his old age, and confident enough in his own abilities that he’s able to negotiate a higher share of the loot. But the prize supporting character is Mouse (Ann Lynn), girlfriend of Dominic’s sidekick Toddy (Charles Kay), who is considered so dumb and harmless that the crooks discuss their plans within her earshot. Except, she’s not concentrating and doesn’t quite get the hang of things and feeds Toddy the wrong information at the wrong time which nearly puts a spoke in the works.

As if the robbery required any more tension. Just how much work is involved in digging a hole through a wall is pretty clear here, should anyone in the audience have ideas of their own. You know double-crossing is also on the cards, not just the Dominic vs Joe and Christine vs Joe but the lovelorn Fina is also due her come-uppance.

And there’s a very nice touch at the end which proves that amateurs are a distinct liability. Any notion Christine has harbored that she would, if only given the chance, prove an ideal getaway driver are misplaced.

Directed by Wolf Rilla (Village of the Damned, 1960) not just with occasional style notes but with a determination to allow his characters room to move from a screenplay by Leigh Vance (Crossplot, 1969). You can catch it on Talking Pictures TV.

All in all a very entertaining little picture strong on tension with a host of interesting characters.